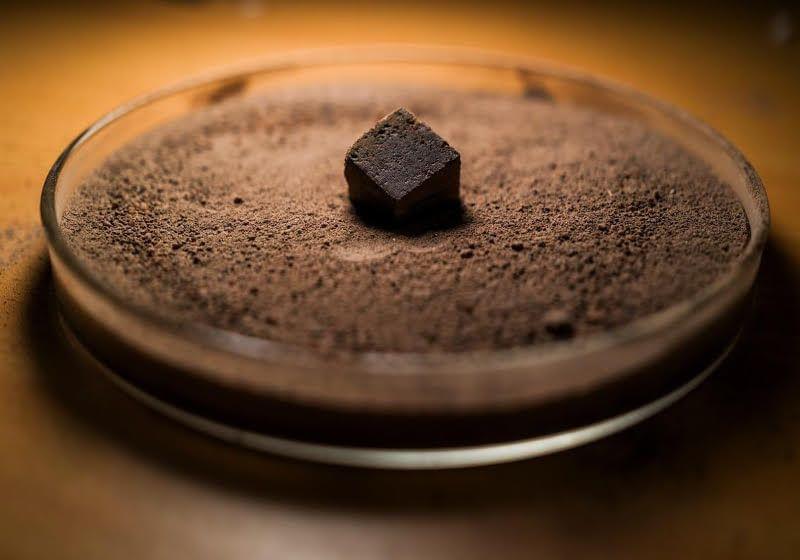

All-perovskite tandem solar cells (TSCs) are a class of solar cells comprised of two or more sub-cells that absorb light with different wavelengths, all of which are made of perovskites (i.e., materials with a characteristic crystal structure known to efficiently absorb light). These solar cells have been found to be highly promising energy solutions, as they could convert sunlight into electricity more efficiently than existing silicon-based solar cells.

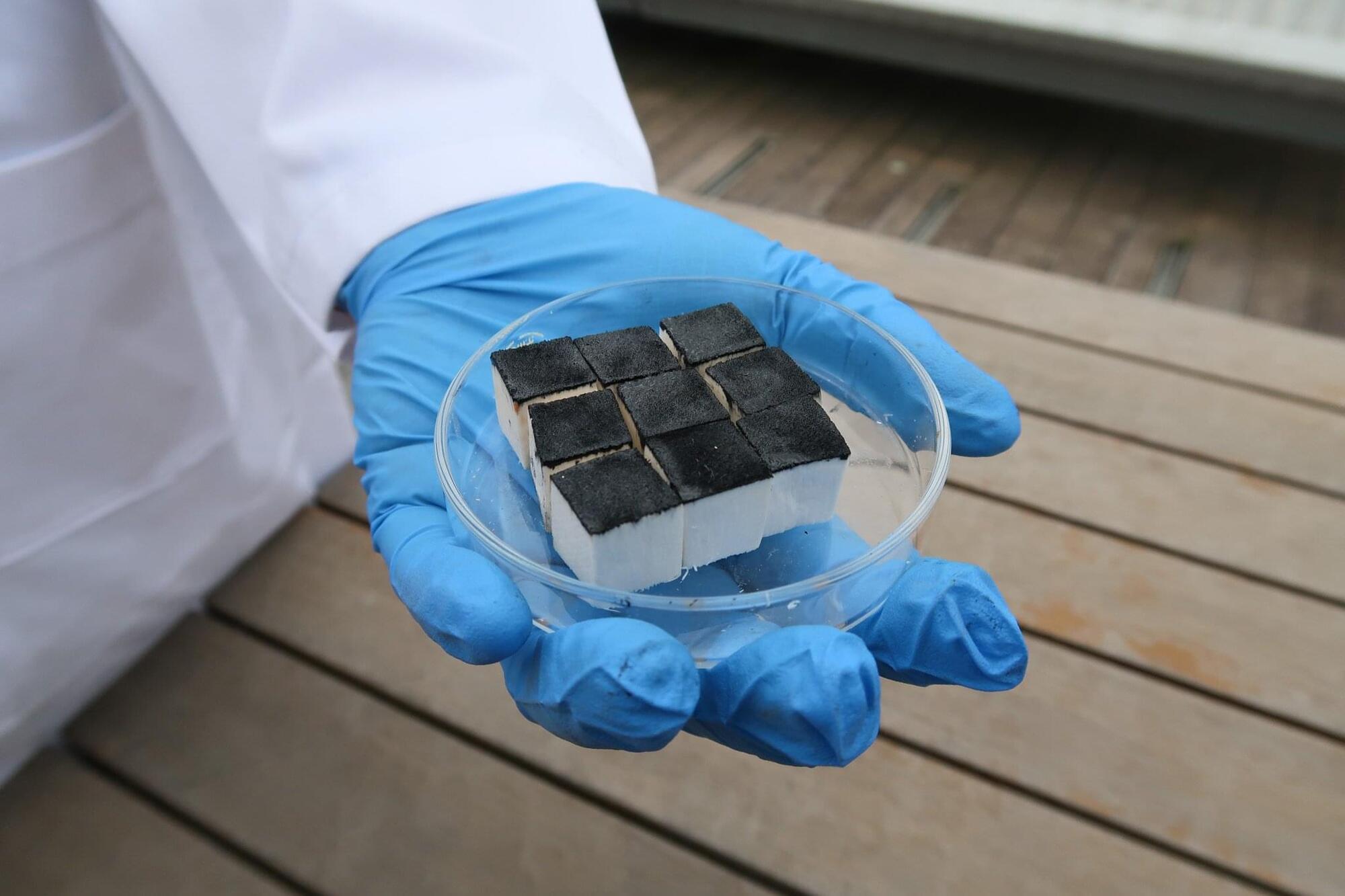

Despite their potential, most all-perovskite TSCs developed to date only perform well when they are small and their performance rapidly declines as their size increases. This has ultimately prevented them from being manufactured and deployed on a large-scale.

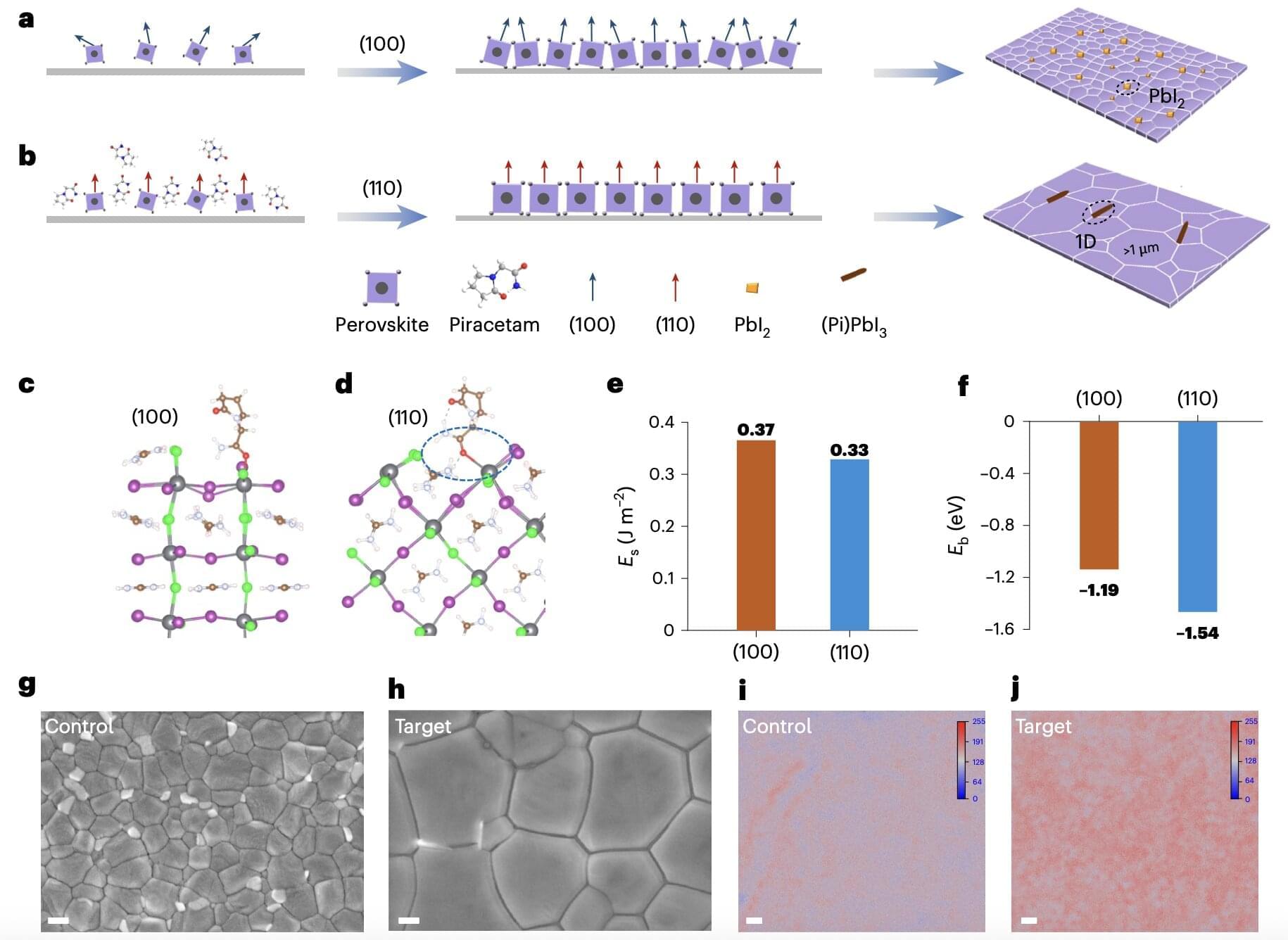

Researchers at Wuhan University and other institutes in China recently introduced a new strategy for enhancing the performance of all-perovskite TSCs irrespective of their size, which could in turn contribute to their future commercialization. Their proposed approach for fabricating these cells, outlined in a paper published in Nature Nanotechnology, entails the use of piracetam, a chemical additive that can help to control the initial phase of crystal formation (i.e., nucleation) in wide-bandgap perovskites.