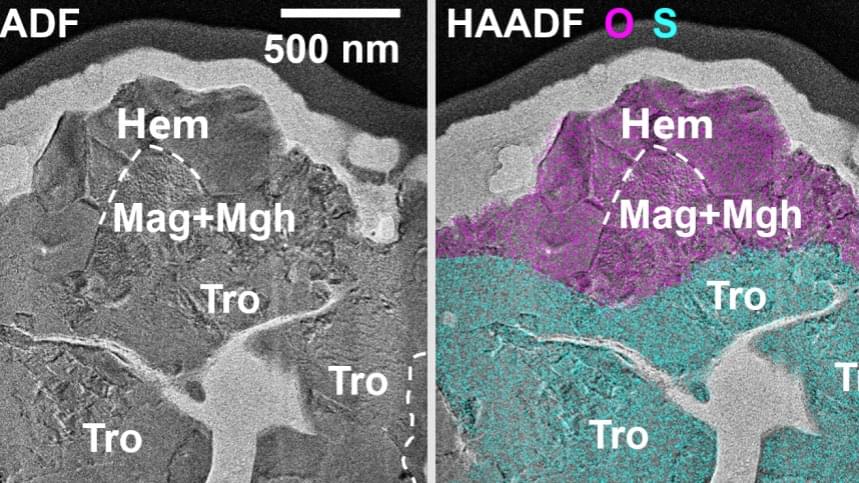

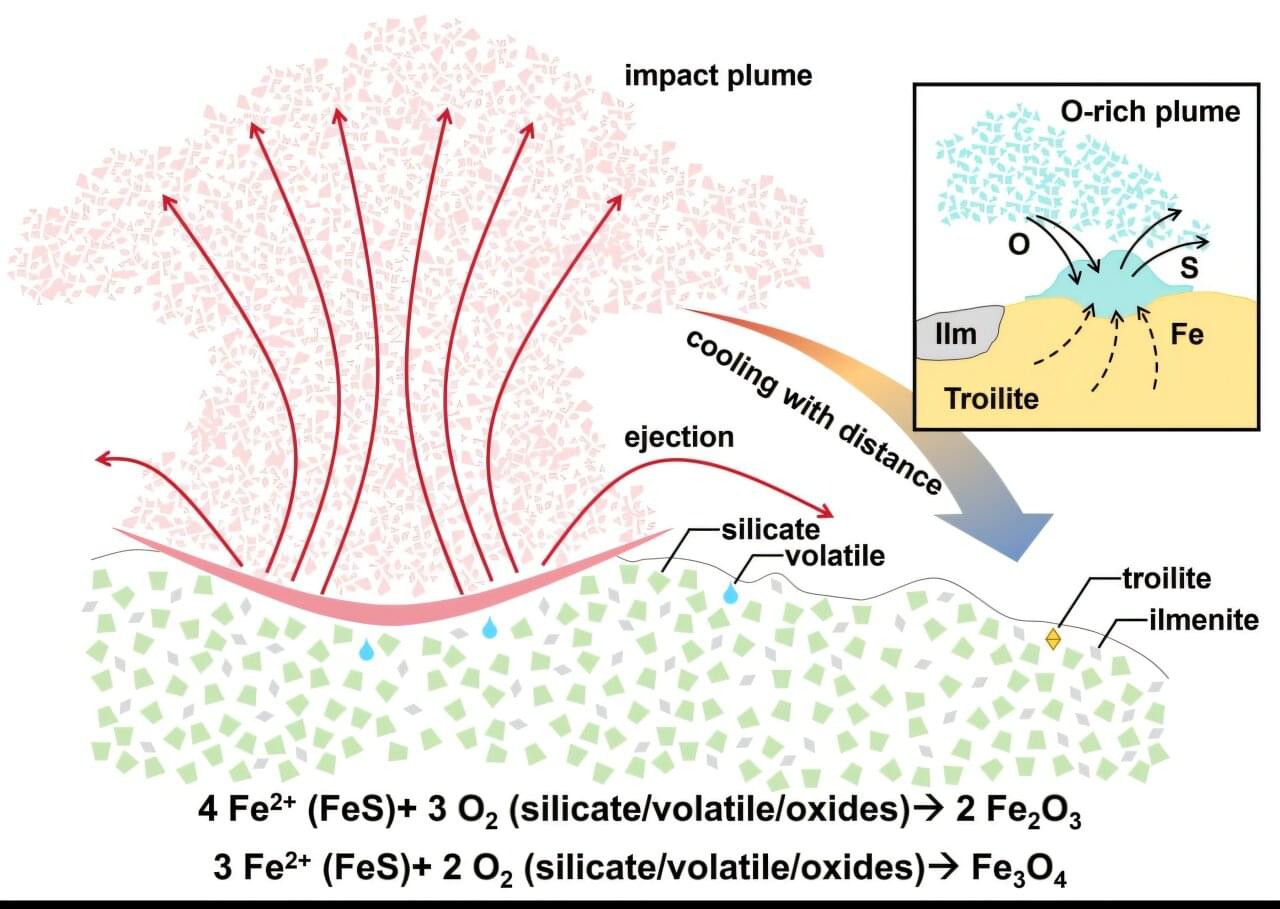

Chinese scientists have, for the first time, identified micrometer-sized crystals of hematite and maghemite in lunar soil samples brought back by the Chang’e 6 mission from the moon’s far side.

This finding, published in the latest issue of the journal Science Advances, reveals a previously unknown oxidation process on the moon. It provides direct sample evidence for the origin of magnetic anomalies around the South Pole-Aitken Basin and challenges the long-standing view that the lunar surface is entirely in a reduced state with minimal oxidation, according to the China National Space Administration.

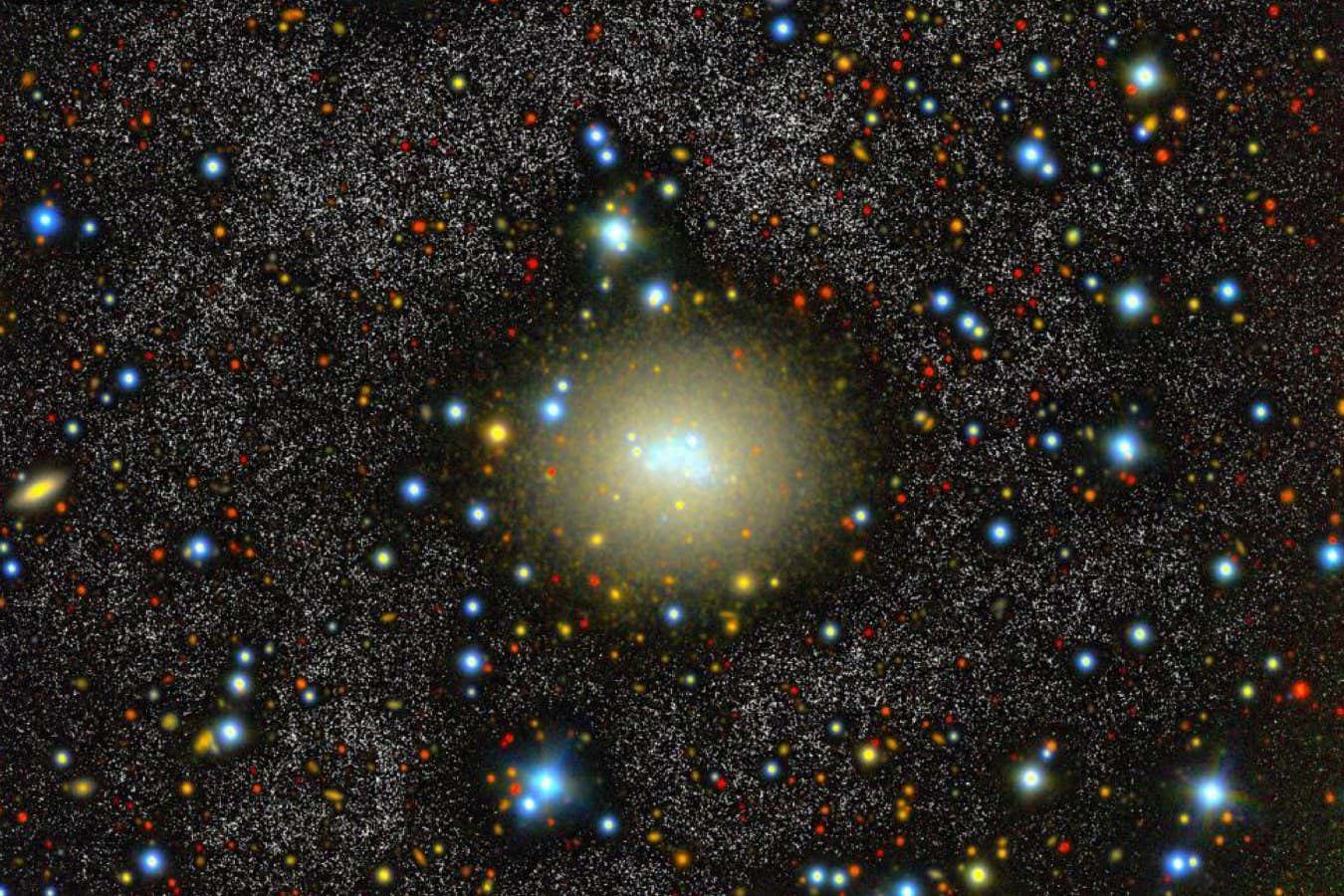

The research, conducted by Shandong University, the Institute of Geochemistry of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and Yunnan University, identified these iron oxides in the Chang’e 6 samples collected from the SPA Basin, the largest and oldest known impact basin in the solar system.