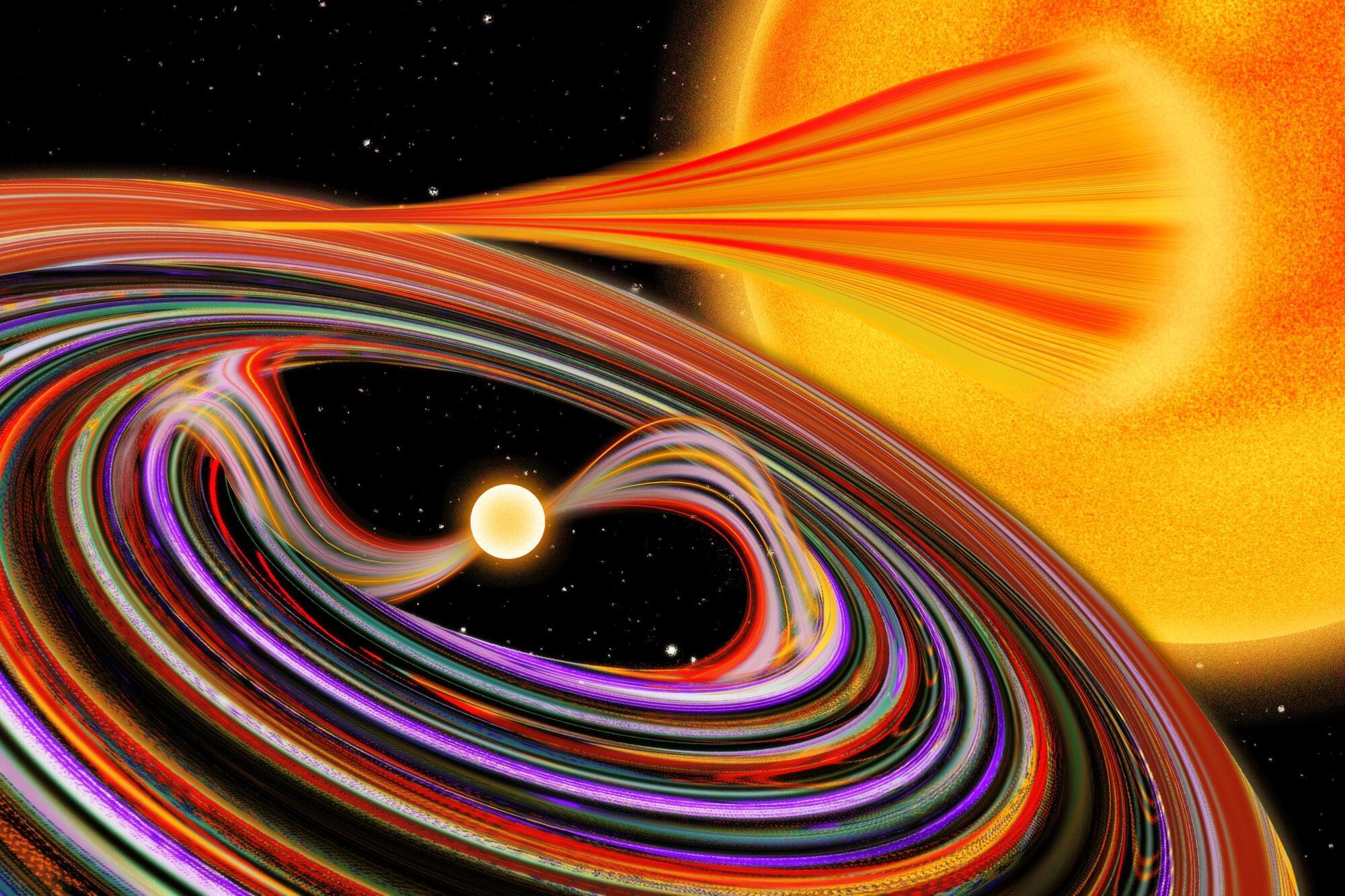

Some 200 light years from Earth, the core of a dead star is circling a larger star in a macabre cosmic dance. The dead star is a type of white dwarf that exerts a powerful magnetic field as it pulls material from the larger star into a swirling, accreting disk. The spiraling pair is what’s known as an “intermediate polar” — a type of star system that gives off a complex pattern of intense radiation, including X-rays, as gas from the larger star falls onto the other one.

Now, MIT astronomers have used an X-ray telescope in space to identify key features in the system’s innermost region — an extremely energetic environment that has been inaccessible to most telescopes until now. In an open-access study published in the Astrophysical Journal, the team reports using NASA’s Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE) to observe the intermediate polar, known as EX Hydrae.

The team found a surprisingly high degree of X-ray polarization, which describes the direction of an X-ray wave’s electric field, as well as an unexpected direction of polarization in the X-rays coming from EX Hydrae. From these measurements, the researchers traced the X-rays back to their source in the system’s innermost region, close to the surface of the white dwarf.