Over 20 years ago, I was interviewed by a group that asked me about the future of technology. I told them due to advancements such as nanotechnology that technology will definitely go beyond laptops, networks, servers, etc.; that we would see even the threads/ fibers in our clothing be digitized. I was then given a look by the interviewers that I must have walked of the planet Mars. However, I was proven correct. And, in the recent 10 years, again I informed others how and where Quantum would change our lives forever. Again, same looks and comments.

And, lately folks have been coming out with articles that they have spoken with or interviewed QC experts. And, they in many cases added their own commentary and cherry picked people comments to discredit the efforts of Google, D-Wave, UNSW, MIT, etc. which is very misleading and negatively impacts QC efforts. When I come across such articles, I often share where and why the authors have misinformed their readers as well as negatively impacted efforts and set folks up for failure who should be trying to plan for QC in their longer term future state strategy so that they can plan for budgets, people can be brought up to date in their understanding of QC because once QC goes live on a larger scale, companies and governments will not have time to catch up because once hackers (foreign government hackers, etc.) have this technology and you’re not QC enabled then you are exposed, and your customers are exposed. The QC revolution will be costly and digital transformation in general across a large company takes years to complete so best to plan and prepare early this time for QC because it is not the same as implementing a new cloud, or ERP, or a new data center, or rationalizing a silo enterprise environment.

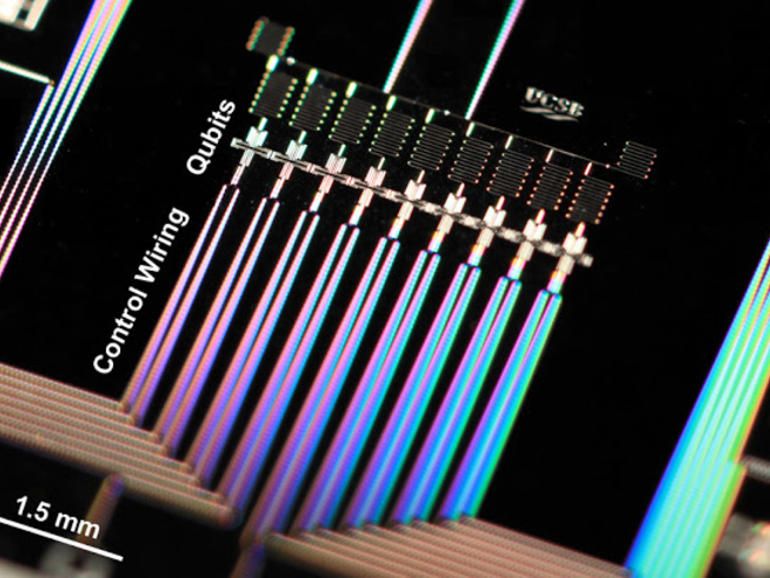

The recent misguided view is that we’re 30 or 50 years away from a scalable quantum chip; and that is definitely incorrect. UNSW has proven scalable QC is achievable and Google has been working on making a scalable QC chip. And, lately RMIT researchers have shared with us how they have proven method to be able to trace particles in the deepest layers of entanglement which means that we now can build QC without the need of analog technology and take full advantage of quantum properties in QC which has not been the case.

So, sharing these three news releases for my QC friends to share with their non-believers and the uninformed.

http://www.zdnet.com/article/googles-quantum-computer-inches…akthrough/

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/10/151030153108.htm