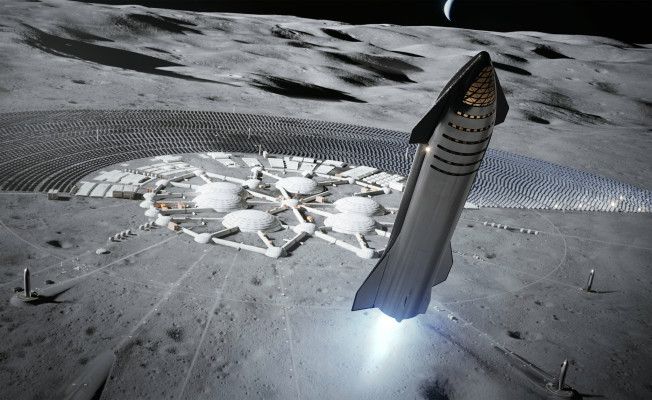

SpaceX CEO and founder Elon Musk says that after accomplishing its first human launch, the company’s primary focus going forward will be developing Starship, its next-generation spacecraft. According to an internal email seen by CNBC, Musk said that Starship is job one for the company, with the exception of ensuring that everything goes well with the forthcoming return of the Crew Dragon capsule from the International Space Station, which will be carrying NASA astronauts Doug Hurley and Bob Behnken on their homeward bound trip.

Starship has been in development at a SpaceX production and testing site in Boca Chica, Texas, since 2019, and was also originally being developed by a second team in parallel in Florida. SpaceX combined the efforts and focused prototype builds in Texas late last year and has been building a number of Starship prototypes using a model of rapid iteration.

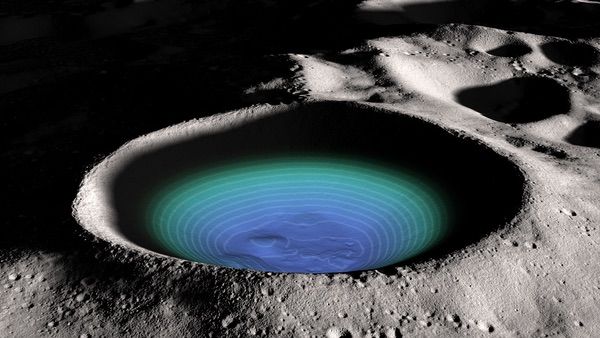

The spacecraft is designed to be a fully reusable vehicle that can support both crew and cargo configurations that can make trips to both Earth orbit and deep space destinations including the moon and Mars when paired with the forthcoming SpaceX Super Heavy rocket booster. SpaceX eventually wants to replace both Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy with Starship, which should reduce costs by unifying its production lines and offering full reusability.