Tailoring and manipulating electromagnetic wave propagation has been of great interest within the scientific community for many decades. In this context, wave propagation has been engineered by properly introducing spatial inhomogeneities along the path where the wave is traveling. Antennas and communications systems in general have greatly benefited from this wave-matter control. For instance, if one needs to re-direct the radiated field (information) from an antenna (transmitter) to a desired direction and reach a receiving antenna placed at a different location, one can simply place the former in a translation stage and mechanically steer the propagation of the emitted electromagnetic wave.

Such beam steering techniques have greatly contributed to the spatial aiming of targets in applications such as radars and point-to-point communication systems. Beam steering can also be achieved using metamaterials and metasurfaces by means of spatially controlling the effective electromagnetic parameters of a designed meta-lens antenna system and/or using reconfigurable meta-surfaces. The next question to ask: Could we push the limits of current beam steering applications by controlling electromagnetic properties of media not only in space but also in time (i.e., 4D metamaterials x, y,z, t)? In order words, would it be possible to achieve temporal aiming of electromagnetic waves?

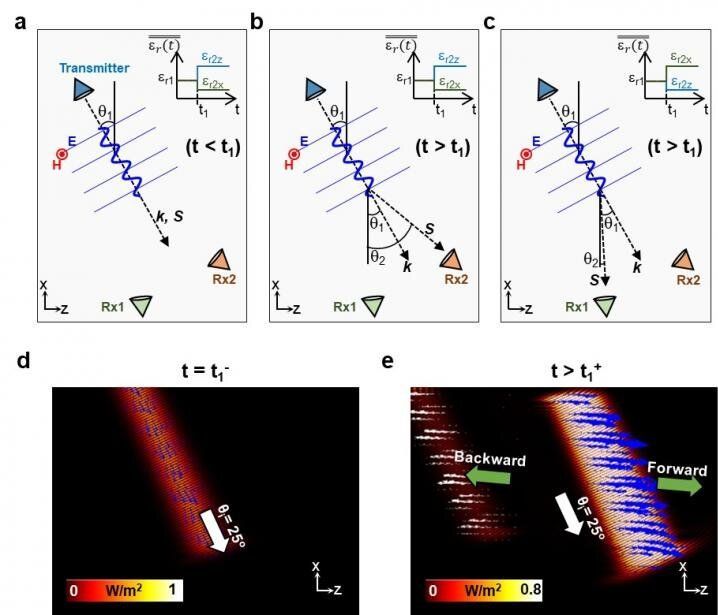

In a new paper published in Light Science & Applications, Victor Pacheco-Peña from the School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics of Newcastle University in UK and Nader Engheta from and Department of Electrical and Systems Engineering of the University of Pennsylvania, USA have answered this question by proposing the idea of temporal metamaterials that change from an isotropic to an anisotropic permittivity tensor. In this concept, the authors consider a rapid change of the permittivity of the whole medium where the wave is traveling and demonstrated both numerically and analytically the effects of such a temporal boundary caused by the rapid temporal change of permittivity. In so doing, forward and backward waves are produced with wave vector k preserved through the whole process while frequency is changed, depending on the values of the permittivity tensor before and after the temporal change of permittivity.