A nation with unique sights and picture opportunities. They also have 92,000 ‘powerful waterlilies’ ignited, marking the end of solar panels as we know them.

The SunRise Building, a residential complex in Alberta, Canada, has established a Guinness World Record for the largest solar panel mural.

The installation combines art with building-integrated photovoltaics (BIPV), contributing to the building’s energy supply. This project measures 34,500 square feet and provides 267 kW of solar capacity, powering the building’s common areas.

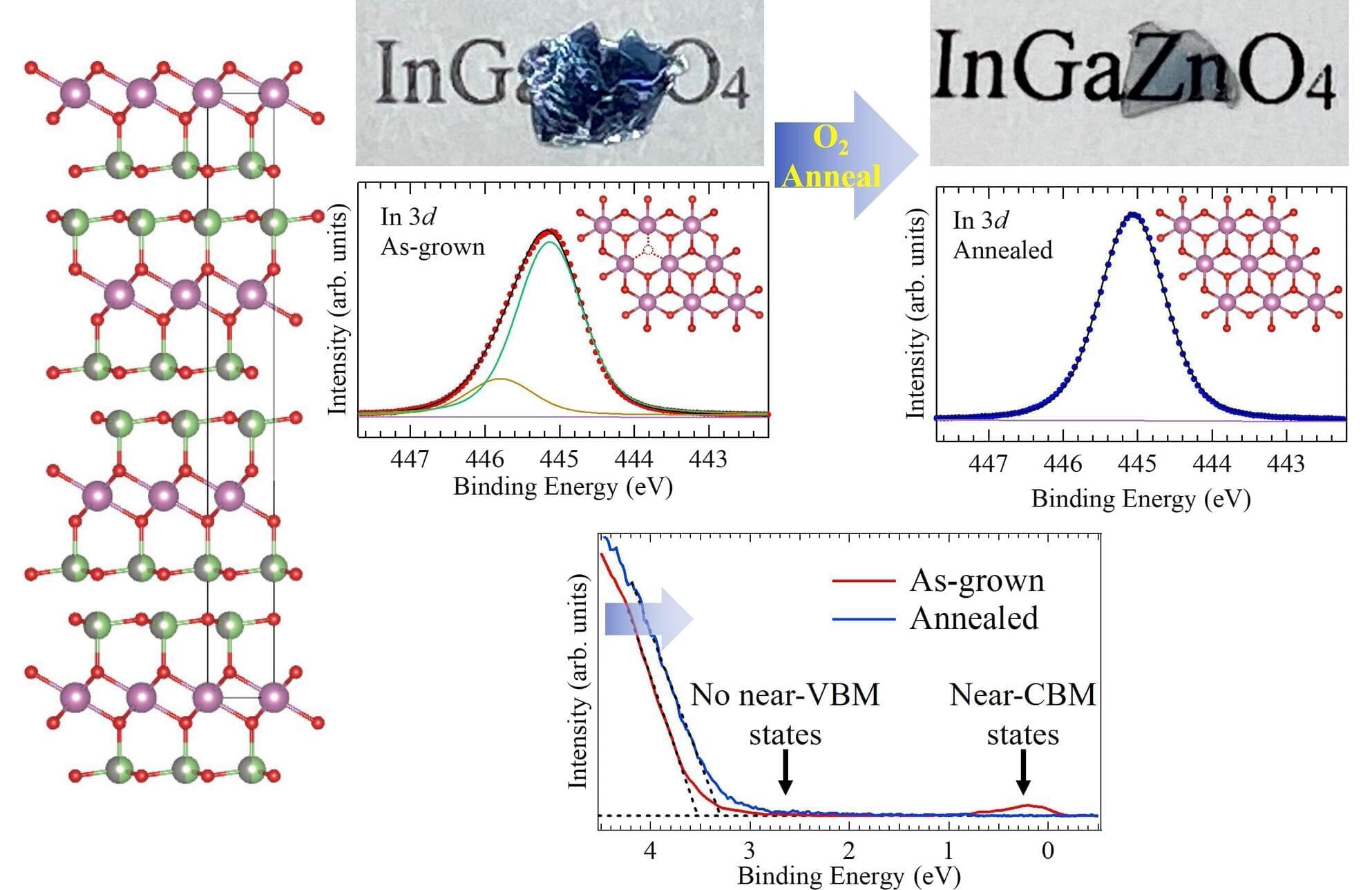

Many displays found in smartphones and televisions rely on thin-film transistors (TFTs) made from indium gallium zinc oxide (IGZO) to control pixels. IGZO offers high transparency due to its large bandgap (the gap existing between the valence and conduction bands), high conductivity, and can operate even in an amorphous (non-crystalline) form, making it ideal for displays, flexible electronics, and solar cells.

However, IGZO-based devices face long-term stability issues, such as negative bias illumination stress, where prolonged exposure to light and electrical stress shifts the voltage required to activate pixels. These instabilities are believed to stem from structural imperfections, which create additional electronic states—known as subgap states—that trap charge carriers and disrupt current flow.

Until recently, most studies on subgap states focused on amorphous IGZO, as sufficiently large single-crystal IGZO (sc-IGZO) samples were not available for analysis. However, the disordered nature of amorphous IGZO has made it difficult to pinpoint the exact causes of electronic instability.

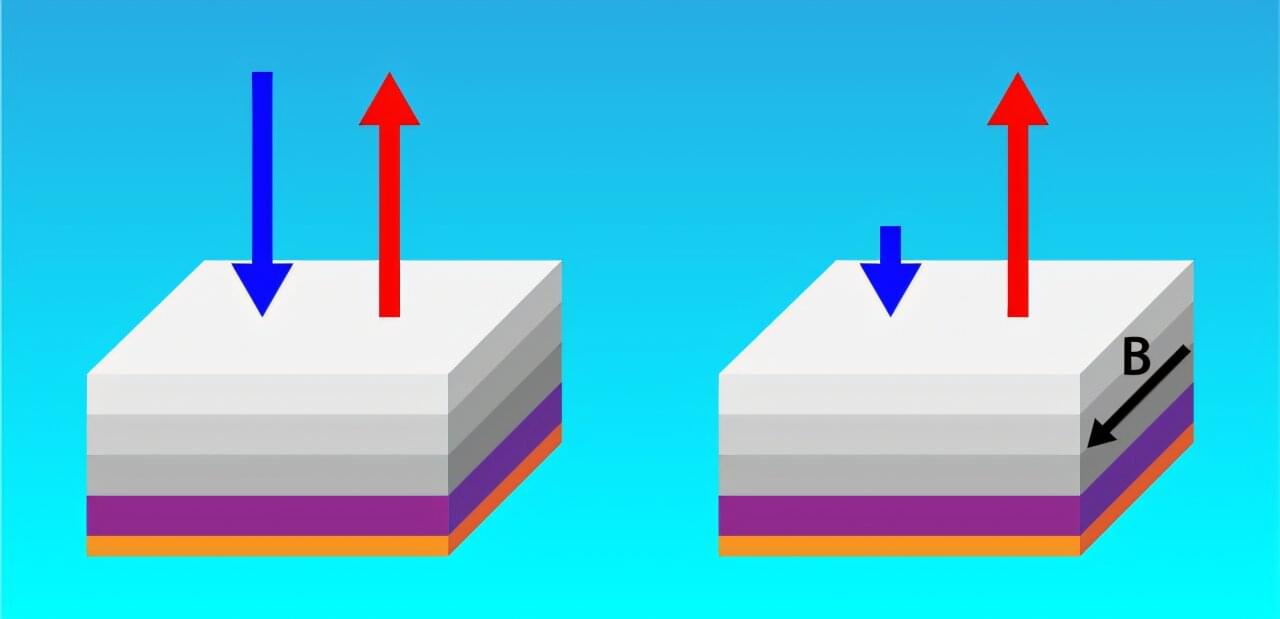

New results published in the journal Physical Review Letters detail how a specially designed metamaterial was able to tip the normally equal balance between thermal absorption and emission, enabling the material to better emit infrared light than absorb it.

At first glance, these findings appear to violate Kirchhoff’s law of thermal radiation, which states that—under specific conditions—an object will absorb infrared light (absorptivity) in one direction and emit it (emissivity) with equal intensity in another, a phenomenon known as reciprocity.

Over the past decade, however, scientists have begun exploring theoretical designs that, under the right conditions, could allow materials to break reciprocity. Understanding how a material absorbs and emits infrared light (heat) is central to many fields of science and engineering. Controlling how a material absorbs and emits infrared light could pave the way for advances in solar energy harvesting, thermal cloaking devices, and other technologies.

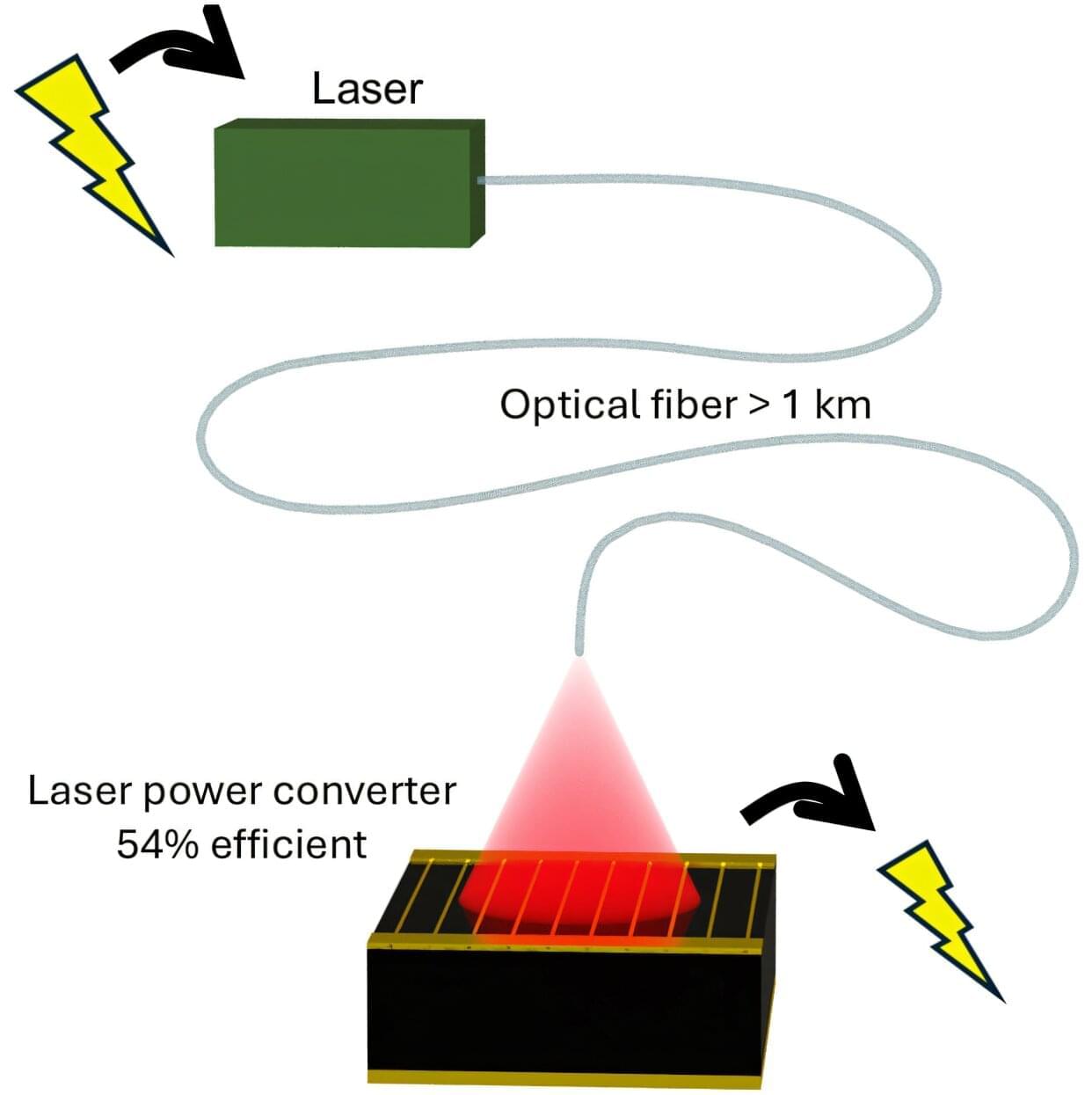

From smart grids to the internet of things, the modern world is increasingly reliant on connectivity between electronic devices. Thanks to University of Ottawa researchers, these devices can now be simultaneously connected and powered with a simple optical fiber over long distances, even in the harshest environments.

This significant step forward in the development of photonic power converters—devices that turn laser light into electrical power —could integrate laser-driven, remote power solutions into existing fiber optic infrastructure. This, in turn, could pave the way for improved connectivity and more reliable communication in remote locations and extreme situations.

“In traditional power over fiber systems, most of the laser light is lost,” explains Professor Karin Hinzer of the University of Ottawa’s SUNLAB, which collaborated with Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems on the study. “With these new devices, the fiber can be much longer.”

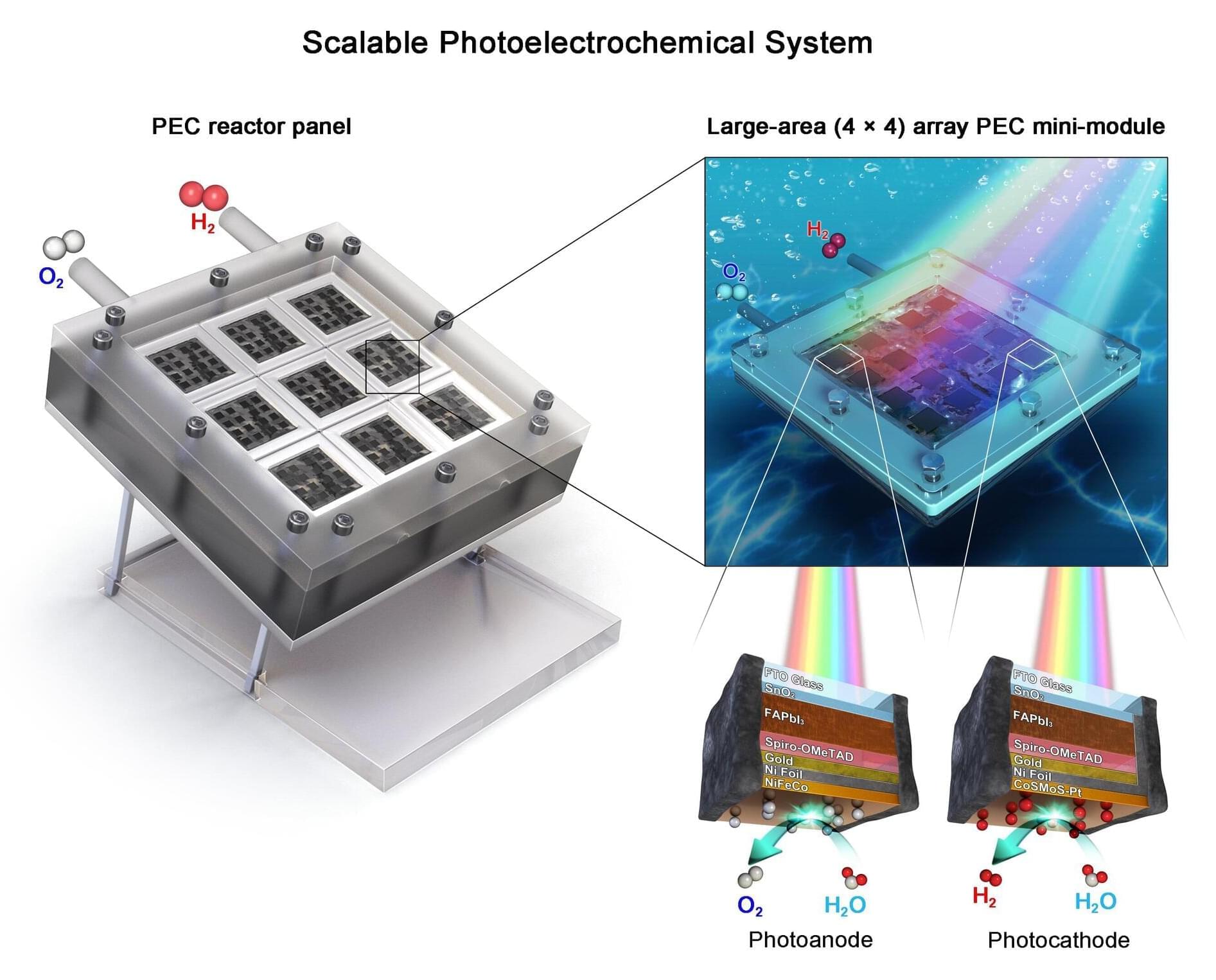

A research team affiliated with UNIST has introduced a cutting-edge modular artificial leaf that simultaneously meets high efficiency, long-term stability, and scalability requirements—marking a major step forward in green hydrogen production technology essential for achieving carbon neutrality.

Jointly led by Professors Jae Sung Lee, Sang Il Seok, and Ji-Wook Jang from the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering, this innovative system mimics natural leaves by producing hydrogen solely from sunlight and water, without requiring external power sources or emitting carbon dioxide during the process—a clean hydrogen production method. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Unlike conventional photovoltaic-electrochemical (PV-EC) systems, which generate electricity before producing hydrogen, this direct solar-to-chemical conversion approach reduces losses associated with electrical resistance and minimizes installation footprint. However, prior challenges related to low efficiency, durability, and scalability hindered commercial deployment.

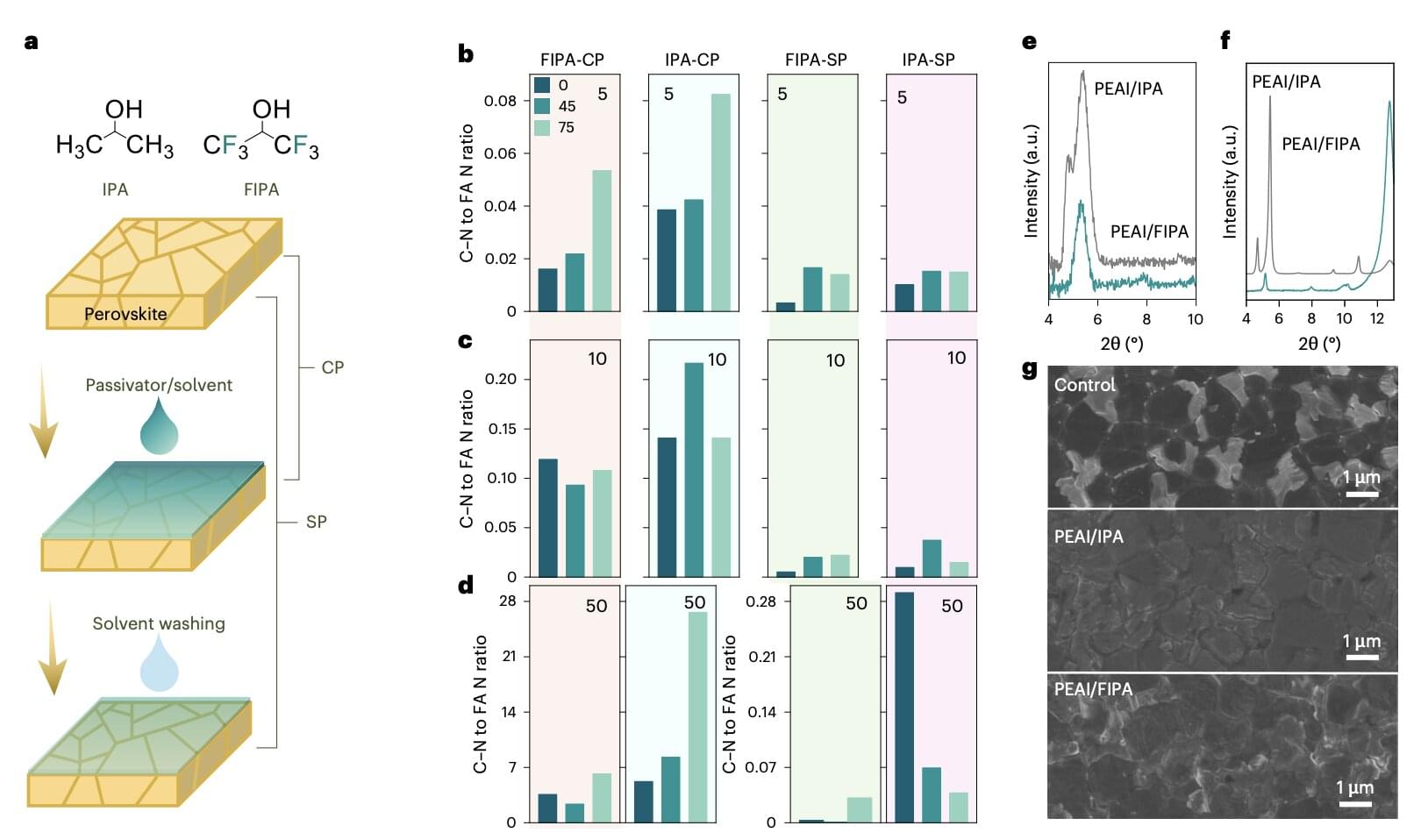

A new study, published in Nature Nanotechnology and featured on the journal’s front cover this month, has uncovered insights into the tiny structures that could take solar energy to the next level.

Researchers from the Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology (CEB) have found that dynamic nanodomains within lead halide perovskites—materials at the forefront of solar cell innovation—hold a key to boosting their efficiency and stability. The findings reveal the nature of these microscopic structures, and how they impact the way electrons are energized by light and transported through the material, offering insights into more efficient solar cells.

The study was led by Milos Dubajic and Professor Sam Stranks from the Optoelectronic Materials and Device Spectroscopy Group at CEB, in collaboration with an international network, with key contributions from Imperial College London, UNSW Sydney, Colorado State University, ANSTO Sydney, and synchrotron facilities in Australia, the UK, and Germany.

Solar cells, devices that can convert sunlight into electrical energy, are becoming increasingly widespread, with many households and industries worldwide now relying on them as a source of electricity. While crystalline silicon-based photovoltaics and other widely available solar cells perform relatively well, manufacturing them can be expensive, and they do not perform well in low-light or other unfavorable conditions.

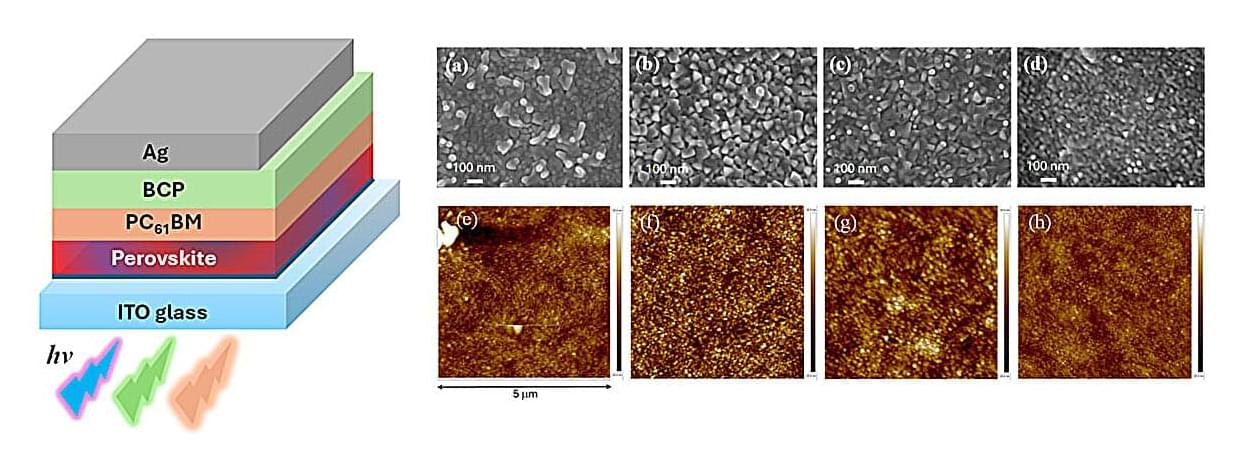

When you think of solar panels, you usually picture giant cells mounted to face the sun. But what if “solar” cells could be charged using fluorescent lights?

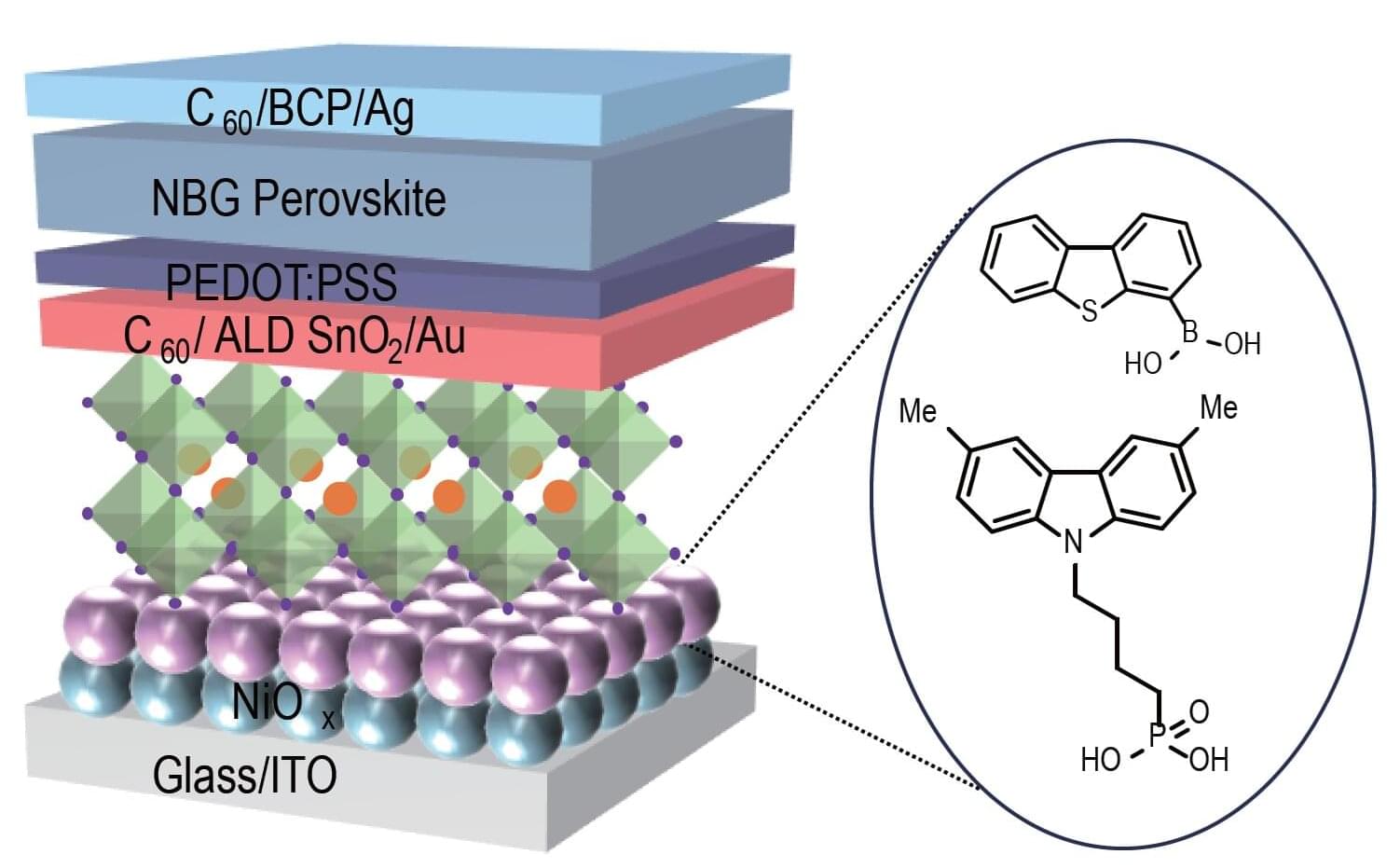

Perovskite solar cells (PeSCs) have emerged as a lower-cost, higher-efficiency alternative to traditional silicon solar cells due to their material structure and physical flexibility. Their large power conversion efficiency rate (PCE), which is the amount of energy created from the amount of energy hitting the cell, makes PeSCs well suited to converting lower light sources into energy.

In APL Energy, researchers from National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University in Taiwan created perovskite solar cells that effectively convert indoor lighting into electrical power.