Brain and Consciousness at New York University, Dr. David Chalmers, about his book Reality+: Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy.

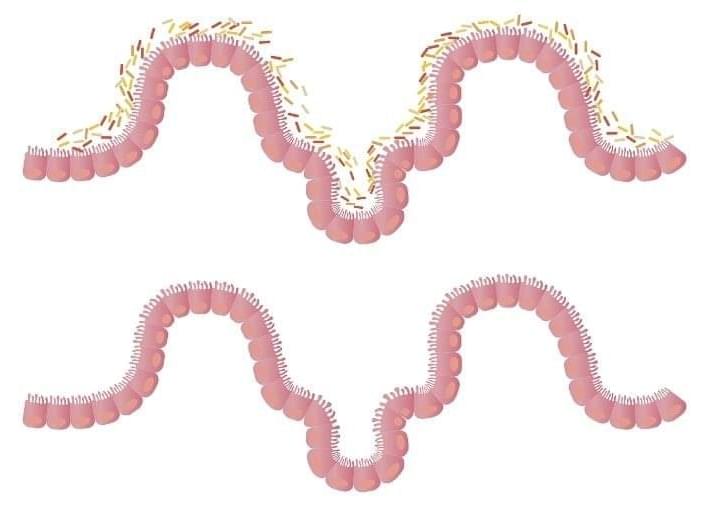

Bacteria might be the solution to all of our space breathing issues. According to Mashable, scientists may use cyanobacteria to figure out how humans might quickly acquire oxygen in space.

Cyanobacteria convert carbon dioxide into oxygen. Cyanobacteria are found in extremely difficult settings on Earth, thus it is predicted that they would be able to live on Mars.

Some scientists have proposed transporting the bacterium to Mars to test whether it can produce oxygen for future people who could end up there. Experiments have previously demonstrated that cyanobacteria can flourish in a Martian environment.

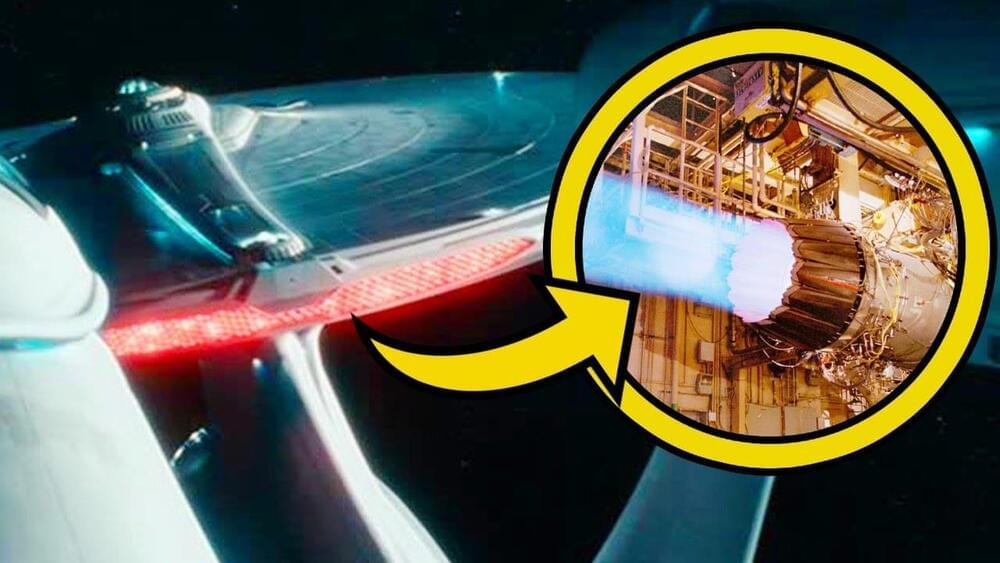

researchers have constructed the largest human genealogy to date, providing insight into key events in human history together with their timings and geographical locations.

Learn more ➡ https://fcld.ly/m4hpr34

The XPrize and other competitions are helping to advance science and technological innovation.

Over the years, we have had alumni go on to become successful academic scientists, company managers and entrepreneurs. The networks that the participants create with each other during the competition are useful to tap into throughout their careers. Recently, I also learnt that a winning team from 2020 decided to create a bioelectronics start-up, INIA Biosciences, that aims to use ultrasound to interact with the immune system to relieve chronic inflammatory diseases.

More companies and foundations are seeing the advantages of science competitions and are organizing innovation challenges. The organizers benefit from recruiting talented people, gaining fresh ideas and promoting an image of innovativeness. The participants are rewarded with training, network building and prize money. In addition to the Innovation Cup, we also organize events such as the €1 million Future Insight Prize, which is given out annually to honour and enable scientists solving key challenges of humanity.

MARJOLEIN CROOIJMANS: The judge

Chair of the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) Entrepreneurship Program Innovation Community (EPIC), Cambridge, Massachusetts and PhD Student at Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands.

Join this channel to get access to perks:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDukC60SYLlPwdU9CWPGx9Q/join.

Neura Pod is a series covering topics related to Neuralink, Inc. Topics such as brain-machine interfaces, brain injuries, and artificial intelligence will be explored. Host Ryan Tanaka synthesizes informationopinions, and conducts interviews to easily learn about Neuralink and its future.

Most people aren’t aware of what the company does, or how it does it. If you know other people who are curious about what Neuralink is doing, this is a nice summary episode to share. Tesla, SpaceX, and the Boring Company are going to have to get used to their newest sibling. Neuralink is going to change how humans think, act, learn, and share information.

Neura Pod:

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/NeuraPod.

- Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/neurapod.

- Medium: https://neurapod.medium.com/

- Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/show/2hqdVrReOGD6SZQ4uKuz7c.

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/NeuraPodcast.

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NeuraPod.

- Tiktok: https://www.tiktok.com/@neurapod.

Opinions are my own. Neura Pod receives no compensation from Neuralink and has no formal affiliations with the company. I own Tesla stock and/or derivatives.

Edited by: Omar Olivares.

Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Russian space agency Roscosmos, issued a stark warning.

The future of the ISS has come into question amid conflict in Ukraine. Dmitry Rogozin, the head of Roscosmos, has warned that blocking cooperation could have catastrophic consequences.

Strategies built by data definitely work.

The overall strength of a professional sports team is measured with one straightforward metric: wins. However, winning one game, let alone a championship, is extremely difficult in professional sports leagues. As the popularity of sports has grown worldwide over the last century, so has the level of competition in professional sports leagues and what it takes to win. Athletes today are bigger, faster, stronger, and more skilled than their counterparts from previous generations. Professional sports organizations need to look for any advantage to help put their teams in the best position to win. More and more pro sports organizations have turned to data science in search of competitive advantages in recent years. One sports team that has consistently used data science as part of its recipe for success is the English football club Liverpool FC. Although all professional football teams feature an analytics department, Liverpool is unique in its approach.

Full Story:

Recesnt success of teams from various sports show the importance of data science in competitive sports.