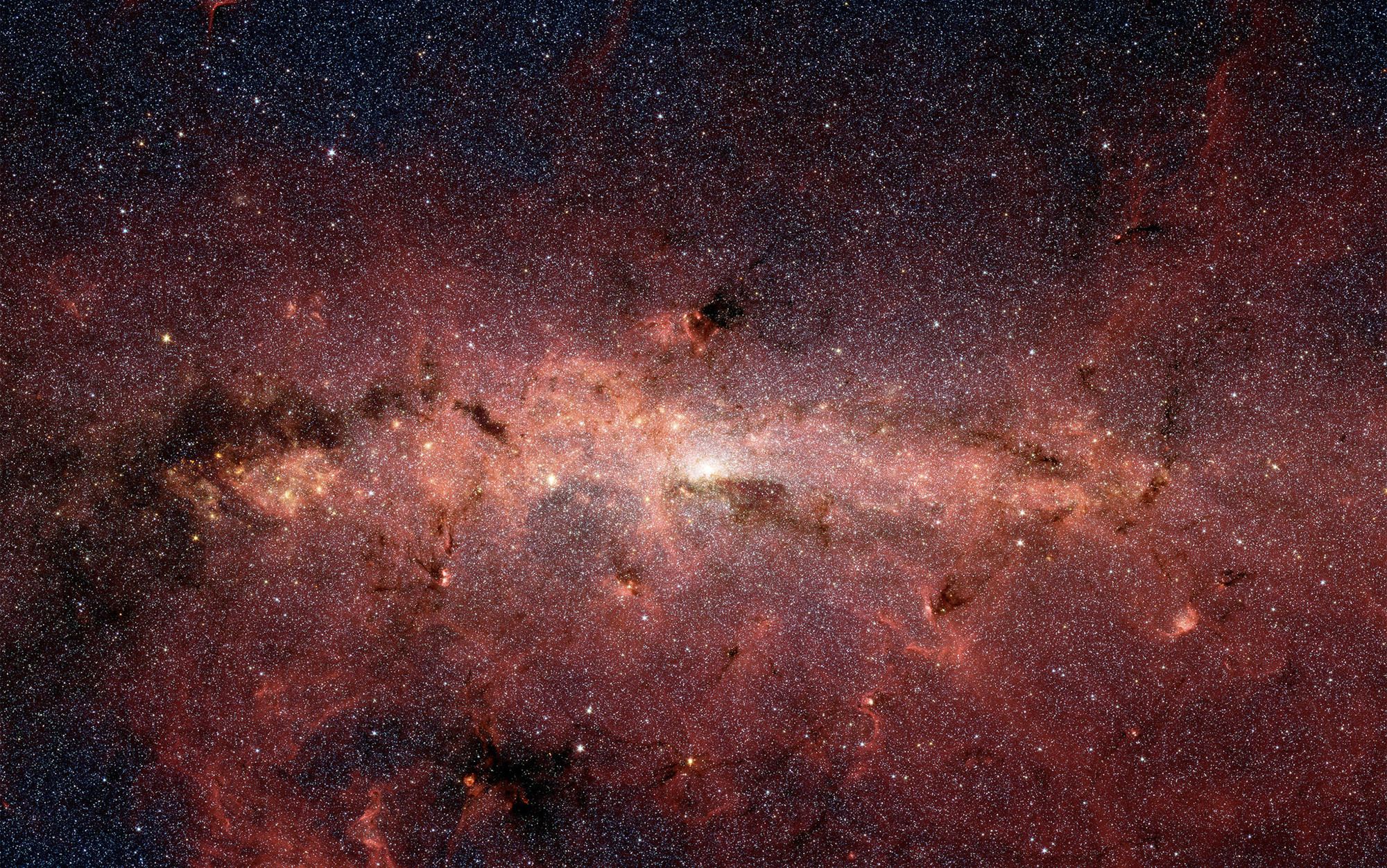

Quantum gravity is a theoretical attempt to reconcile general relativity and the quantum field theories of particle physics. The theory holds that space and time are both quantized in a way that quantum field theory doesn’t account for. Attempts to find evidence in support of the theory have focused on the gravitational effects of black holes. Now, some are using the data collected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) project that has now detected two instances of gravitational waves from the collision of black holes. And there are hints that the data has the evidence the researchers are looking for.

But Afshordi’s idea overthrows what physicists believed they knew about black holes. In Albert Einstein’s theory of general relativity, the event horizon of a black hole – the surface beyond which there is no escape – is insubstantial. Nothing special happens upon crossing it, just that there is no turning around later. If Afshordi is right, however, the inside of the black hole past the event horizon no longer exists. Instead, a Planck-length away from where the horizon would have been, quantum gravitational effects become large, and space-time fluctuations go wild. (The Planck length is a minuscule distance: about 10-35 metres, or 10-20 times the diameter of a proton.) It’s a complete break with relativity.

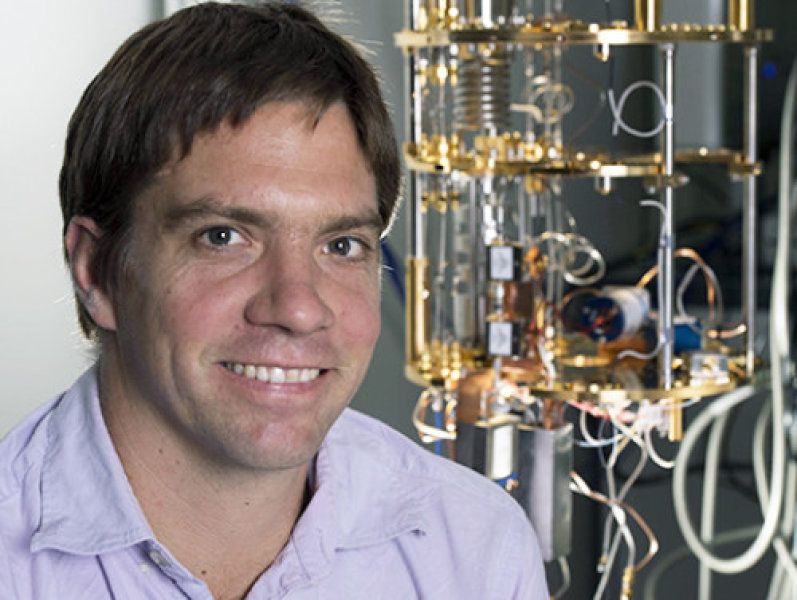

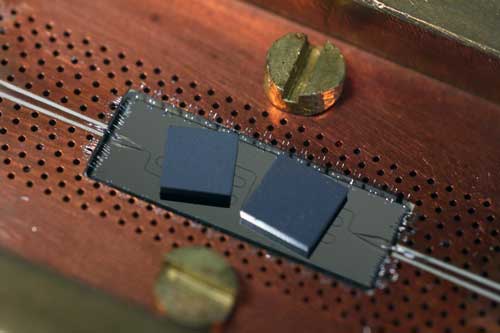

When he heard of the LIGO results, Afshordi realised that his so-far entirely theoretical idea could be observationally tested. If event horizons are different than expected, the gravitational-wave bursts from merging black holes should be different, too. Events picked up by LIGO should have echoes, a subtle but clear signal that would indicate a departure from standard physics. Such a discovery would be a breakthrough in the long search for a quantum theory of gravity. ‘If they confirm it, I should probably book a ticket to Stockholm,’ Afshordi said, laughing.