Our physical space-time reality isn’t really “physical” at all, its apparent solidity of objects, as well as any other associated property such as time, is an illusion. As a renowned physicist Niels Bohr once said: “Everything we call real is made of things that cannot be regarded as real.” But what’s not an illusion is your subjective experience, i.e., your consciousness; that’s the only “real” thing, according to proponents of Experiential Realism. It refers to interacting entangled conscious agents at various ontological levels, giving rise to conscious experience all the way down, and I’d argue all the way up, seemingly ad infinitum. It’s a “matryoshka” of embedded realities: conscious minds within larger minds.

#ExperientialRealism

So, why Experiential Realism? From the bigger picture perspective, we are here for experience necessary for evolution of our conscious minds. Our limitations, such as our ego, belief traps, political correctness, our very human condition define who we are, but the realization that we largely impose those limitations on ourselves gives us more evolvability and impetus to overcome these self-imposed limits to move towards higher goals and state of being.

We are what we’ve experienced — the sum of our experiences define who we are. In this sense, as free will agents, we are co-creators within this experiential matrix. Non-duality is the essence of Experiential Realism — experience and experiencer are one. How can you possibly separate your own existence from the world, the observer from the observed? Today, philosophers and scientists argue that information is fundamental but consciousness is required to assign meaning to it. That makes consciousness (our experience in a broader sense) the most fundamental, irreducible ground of existence itself, while some philosophers suggest consciousness is all that is.

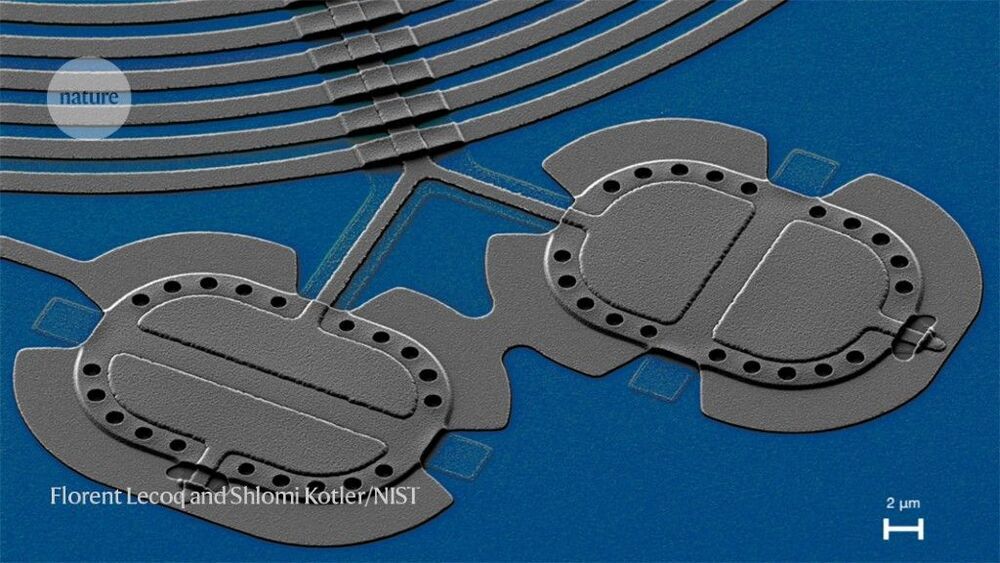

Experiential realism refers to interacting entangled conscious agents at various ontological levels, giving rise to conscious experience all the way down, and I’d argue all the way up, seemingly ad infinitum. It is a “matryoshka” of embedded realities: conscious minds within larger minds. Experiential Realism is a non-physicalist, monistic idealism. It is not to be confused with Naïve Realism, the idea that we see the world around us objectively, as it is. We don’t. Just the opposite is true. Experiential Realism is predicated on the centrality of observers and all-encompassing quantum computational principles. The objective world, i.e., the world whose existence does not depend on the perceptions of a particular observer, consists entirely of conscious agents, more precisely their experiences. What exists in the objective world, independent of your perceptions, is a world of conscious agents, not a world of unconscious particles and fields.