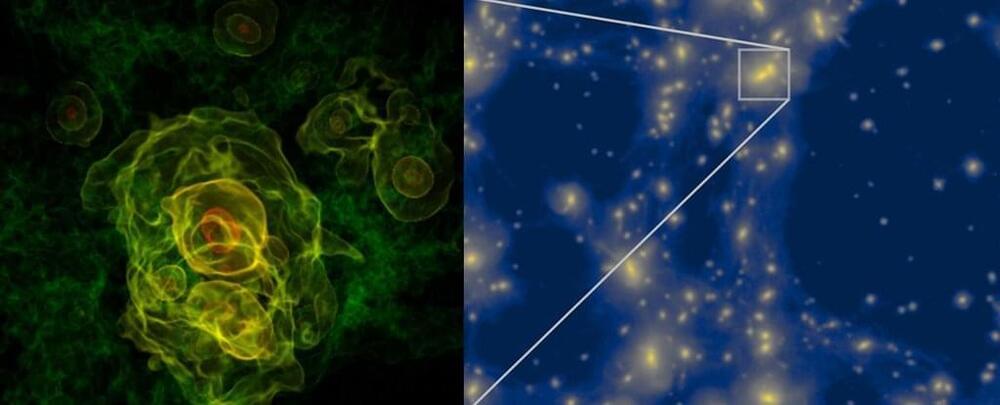

Quantum computing, though still in its early days, has the potential to dramatically increase processing power by harnessing the strange behavior of particles at the smallest scales. Some research groups have already reported performing calculations that would take a traditional supercomputer thousands of years. In the long term, quantum computers could provide unbreakable encryption and simulations of nature beyond today’s capabilities.

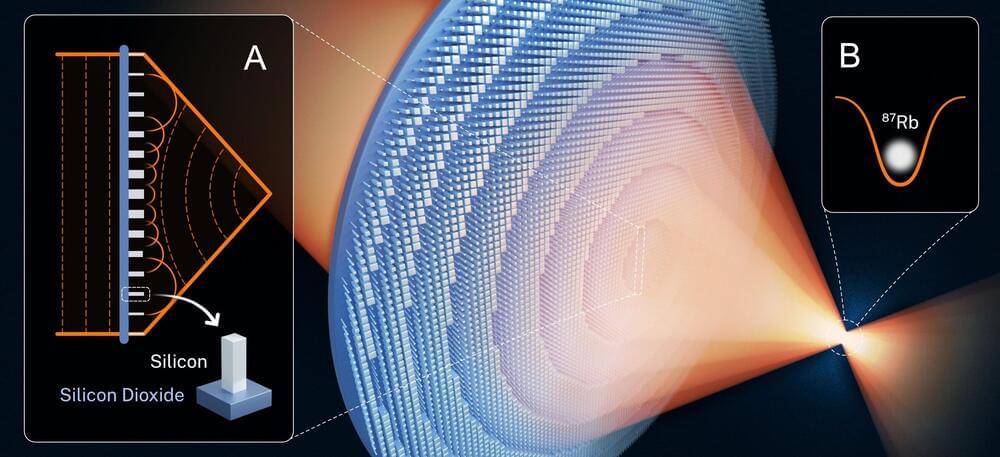

A UCLA-led interdisciplinary research team including collaborators at Harvard University has now developed a fundamentally new strategy for building these computers. While the current state of the art employs circuits, semiconductors and other tools of electrical engineering, the team has produced a game plan based in chemists’ ability to custom-design atomic building blocks that control the properties of larger molecular structures when they’re put together.

The findings, published last week in Nature Chemistry, could ultimately lead to a leap in quantum processing power.