O.o! If the universe is some sorta hologram then this could be a clue to our actual reality.

Last December, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded for experimental evidence of a quantum phenomenon that has been known for more than 80 years: entanglement. As envisioned by Albert Einstein and his collaborators in 1935, quantum objects can be mysteriously correlated even when separated by great distances. But as strange as the phenomenon may seem, why is such an old idea still worthy of the most prestigious award in physics?

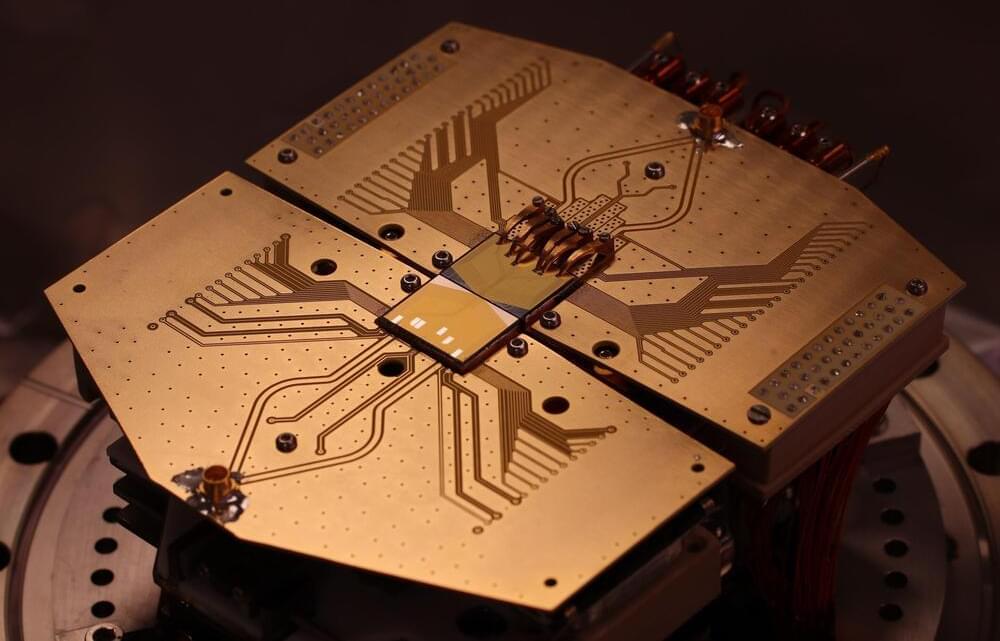

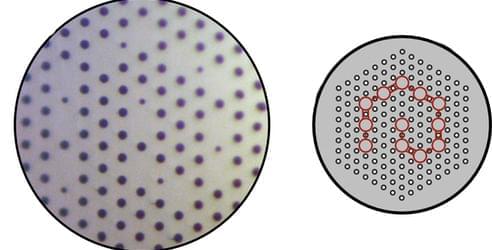

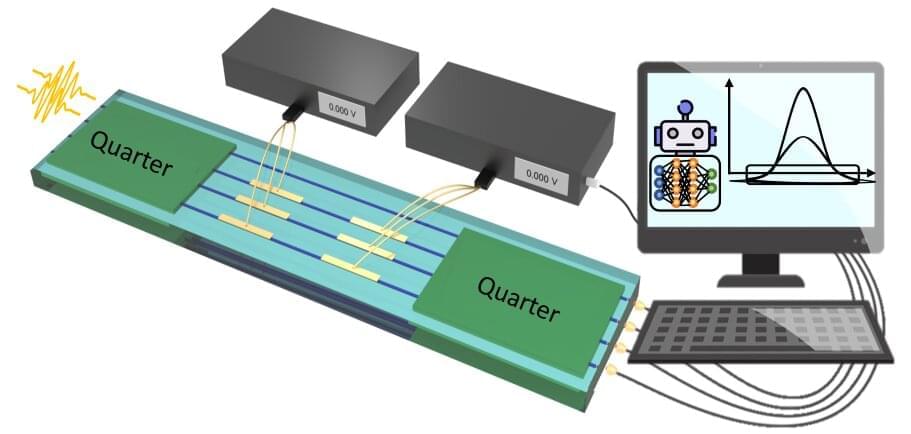

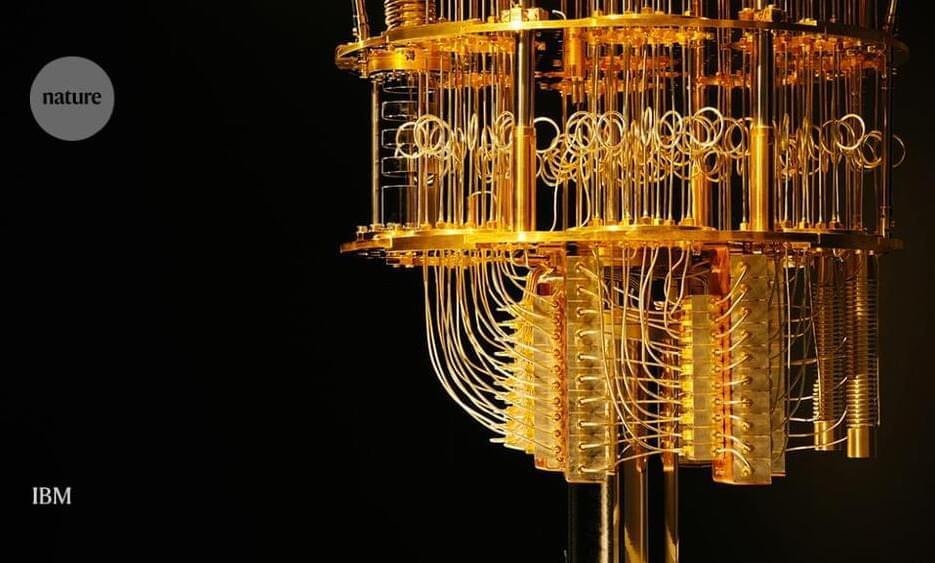

Coincidentally, just weeks before the new Nobel laureates were honored in Stockholm, another team of respected scientists from Harvard, MIT, Caltech, Fermilab and Google reported that they ran a process on Google’s quantum computer that could be interpreted as a wormhole. Wormholes are tunnels through the universe that can function as a shortcut through space and time and are loved by science fiction fans, and although the tunnel realized in this latest experiment only exists in a two-dimensional toy universe, it could be a breakthrough for the future represent research at the forefront of physics.

But why does entanglement have to do with space and time? And how can it be important for future breakthroughs in physics? Properly understood, entanglement means that the universe is what philosophers call “monistic,” that is, at the most fundamental level, everything in the universe is part of a single, unified whole. It is a defining property of quantum mechanics that its underlying reality is described in terms of waves, and a monistic universe would require universal functioning. Decades ago, researchers such as Hugh Everett and Dieter Zeh showed how our everyday reality can emerge from such a universal quantum mechanical description. But it is only now that researchers such as Leonard Susskind and Sean Carroll are developing ideas as to how this hidden quantum reality could explain not only matter but also the structure of space and time.