Quantum mechanics requires a willingness to embrace the inherent unpredictability of the world and the crucial role of the observer. A wave function collapse serves as the interface between the quantum and phenomenal.

Category: quantum physics – Page 576

New quantum state boosts material’s conductivity by a billion percent

Scientists at Georgia Tech have discovered a new quantum state in a quirky material. In a phenomenon never before seen in anything else, the team found that applying a magnetic field increased the material’s electrical conductivity by a billion percent.

Some materials are known to change their conductivity in response to a changing magnetic field, a property called magnetoresistance. But in the new study, the material does so to an incredible degree, exhibiting colossal magnetoresistance.

The material is an alloy of manganese, silicon and tellurium, which takes the form of octagonal cells arranged in a honeycomb pattern, and stacked in sheets. Electrons move around the outside of those octagons, but when there’s no magnetic field applied they travel in random directions, causing a traffic jam. That effectively makes the material act like an insulator.

Quantum Mechanics Helps Physicists Pull Energy Out of Thin Air as Evident in Two Separate Experiments

A shelved theory seems to have given new life to energy teleportation, a concept that pulls energy from one location to another. The notion might sound like science fiction, but some scientists demonstrated that it is possible to generate energy out of thin air.

According to The Space Academy, scientists were able to extract energy and filled a vacuum through two separate experiments. It has indeed opened a fresh world of quantum energy physics.

Physicists Levitated a Glass Nanosphere, Nudging It Into The Realm of Quantum Mechanics

Quantum mechanics deals with the behavior of the Universe at the super-small scale: atoms and subatomic particles that operate in ways that classical physics can’t explain.

In order to explore this tension between the quantum and the classical, scientists are constantly attempting to get larger and larger objects to behave in a quantum-like way.

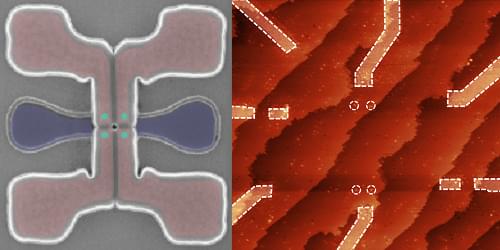

Back in 2021, a team succeeded with a tiny glass nanosphere that was 100 nanometers in diameter – about a thousand times smaller than the thickness of a human hair.

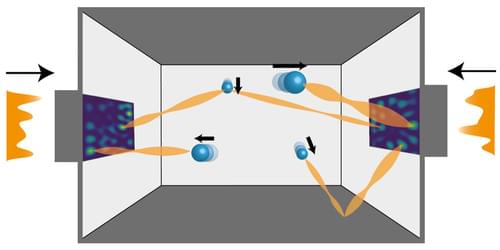

Freezing Particle Motion with a Matrix

Researchers predict that the “scattering matrix” of a collection of particles could be used to slow the particles down, potentially allowing for the cooling of significantly more particles than is possible with current techniques.

When light travels through an environment containing many particles, information about the collective motion of the particles gets added to the light. This information leaves a measurable signature on a quantity known as the scattering matrix. Now researchers from the Vienna University of Technology predict that the information in this matrix could be used to alter the speeds of the particles [1, 2]. The team says that, if experimentally realized, the technique could allow scientists to study the collective quantum behavior of more particles than is possible with current techniques.

Researchers have long been fascinated with using light to slow down or even freeze the motion of a collection of particles. One motivation is that cooled particles can be isolated from outside influences in order to study quantum behaviors such as entanglement. To date, researchers have simultaneously cooled one or two particles, but they have struggled to scale techniques to cool additional particles.

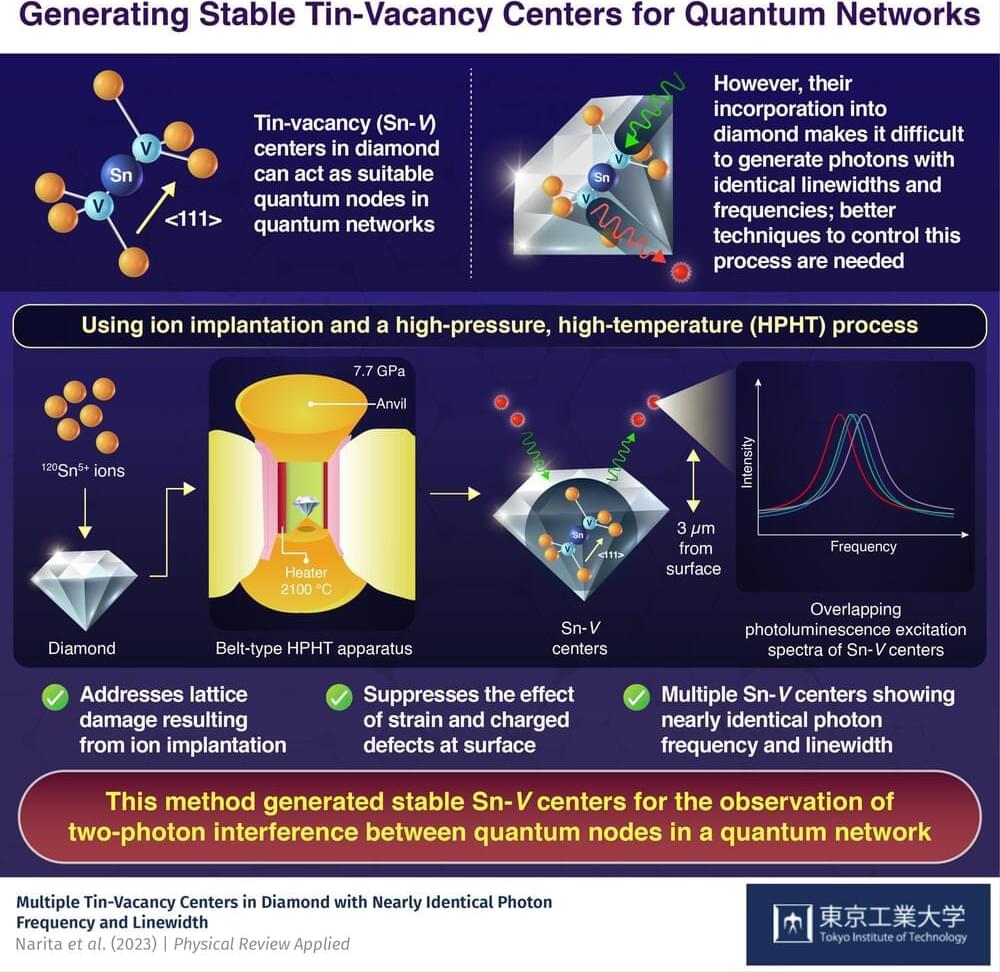

Breakthrough in tin-vacancy centers for quantum network applications

Quantum entanglement refers to a phenomenon in quantum mechanics in which two or more particles become linked such that the state of each particle cannot be described independently of the others, even when they are separated by a large distance. The principle, referred to by Albert Einstein as “spooky action at a distance,” is now utilized in quantum networks to transfer information. The building blocks of these networks—quantum nodes—can generate and measure quantum states.

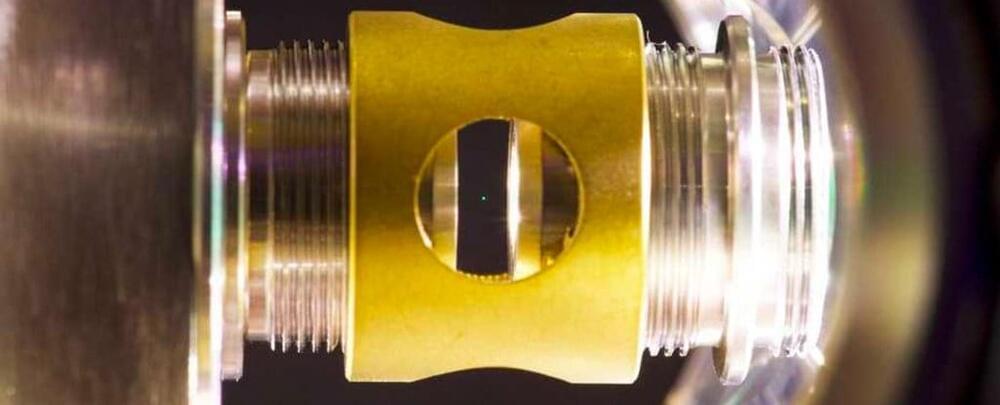

Among the candidates that can function as quantum nodes, the Sn-V center in diamond (a defect where a tin (Sn) atom replaces a carbon atom, resulting in an interstitial Sn atom between two carbon vacancies) has been shown to have suitable properties for quantum network applications.

The Sn-V center is expected to exhibit a long spin coherence time in the millisecond range at Kelvin temperatures, allowing it to maintain its quantum state for a relatively long period of time. However, these centers have yet to produce photons with similar characteristics, which is a necessary criterion for creating remote entangled quantum states between quantum network nodes.

A new neutrino laboratory at the bottom of the Mediterranean for probing sea and sky

The Laboratoire Sous-marin Provence Méditerranée (LSPM) lies 40 km off the coast of Toulon, at a depth of 2,450 m, inaccessible even to sunlight. Through this national research platform run by the CNRS in collaboration with Aix-Marseille University (AMU) and IFREMER, scientists will investigate undersea unknowns while scanning the skies for neutrinos. These elementary particles of extraterrestrial origin know few obstacles and can even traverse our planet without bumping into a single atom.

The main instrument at the LSPM is KM3NeT, a giant neutrino detector developed by a team of 250 researchers from 17 countries. In the pitch-black abyss, KM3NeT will study the trails of bluish light that neutrinos leave in the water. Capable of detecting dozens of these particles a day, it will help elucidate their quantum properties, which still defy our understanding.

The other LSPM instruments will permit the scientific community to study the life and chemistry of these depths. They will offer researchers insights into ocean acidification, deep-sea deoxygenation, marine radioactivity, and seismicity, and allow them to track cetacean populations as well as observe bioluminescent animals. This oceanographic instrumentation is integrated into the subsea observatory network of the EMSO European research infrastructure.