With each of these splittings, the universe completely remolded itself. New particles arose to replace ones that could exist only in extreme conditions previously. The fundamental quantum fields of space-time that dictate how particles and forces interact with each other reconfigured themselves. We do not know how smoothly or roughly these phase transitions took place, but it’s perfectly possible that with each splitting, the universe settled into multiple identities at once.

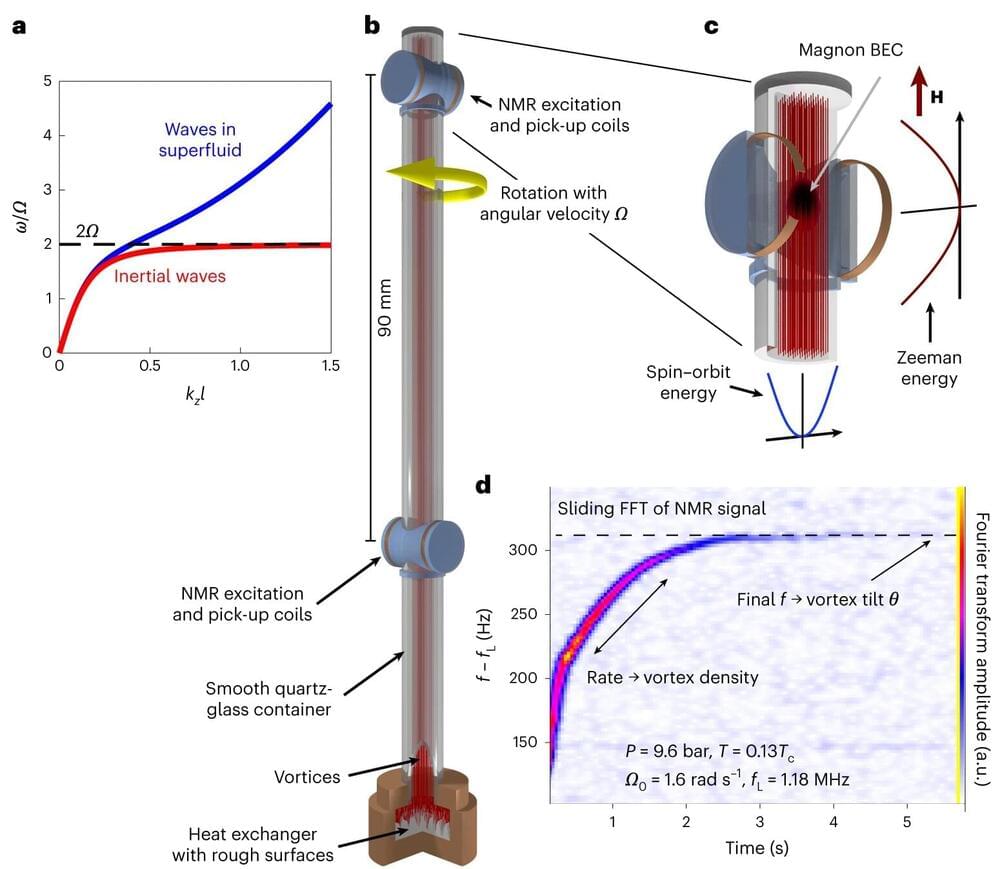

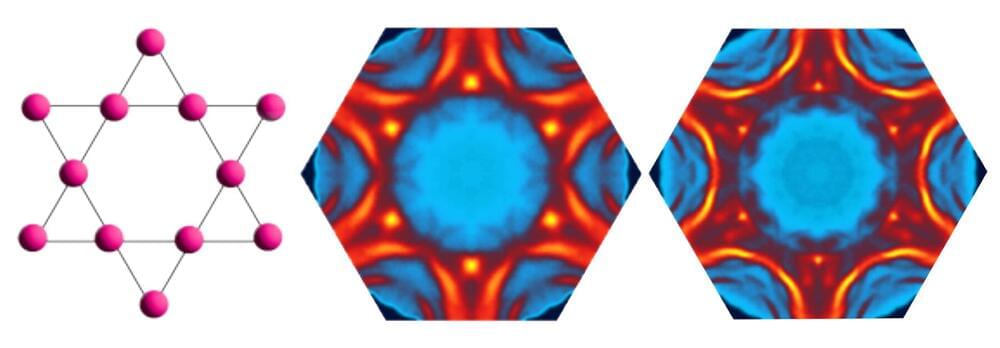

This fracturing isn’t as exotic as it sounds. It happens with all kinds of phase transitions, like water turning into ice. Different patches of water can form ice molecules with different orientations. No matter what, all the water turns into ice, but different domains can have differing molecular arrangements. Where those domains meet walls, or imperfections, fracturing will appear.

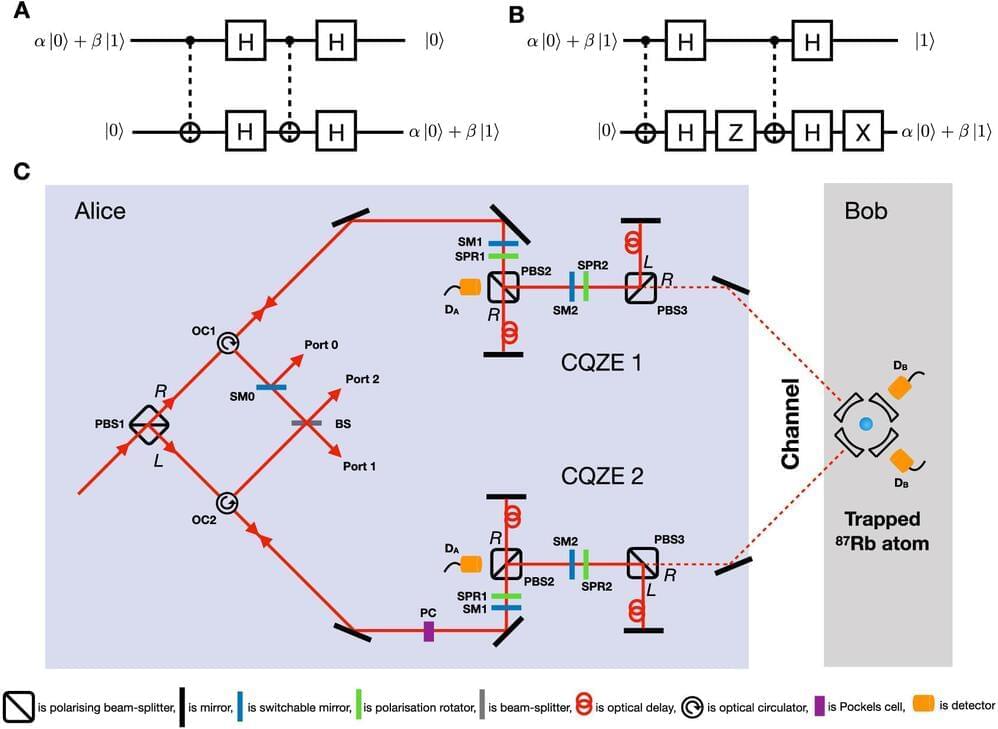

Physicists are especially interested in the so-called GUT phase transition of our universe. GUT is short for “grand unified theory,” a hypothetical model of physics that merges the strong nuclear force with electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force. These theories are just beyond the reach of current experiments, so physicists and astronomers turn to the conditions of the early universe to study this important transition.