All known natural phenomena fit into just a few categories and unifying them all is quantum field theory, says physicist Matt Strassler.

All known natural phenomena fit into just a few categories and unifying them all is quantum field theory, says physicist Matt Strassler.

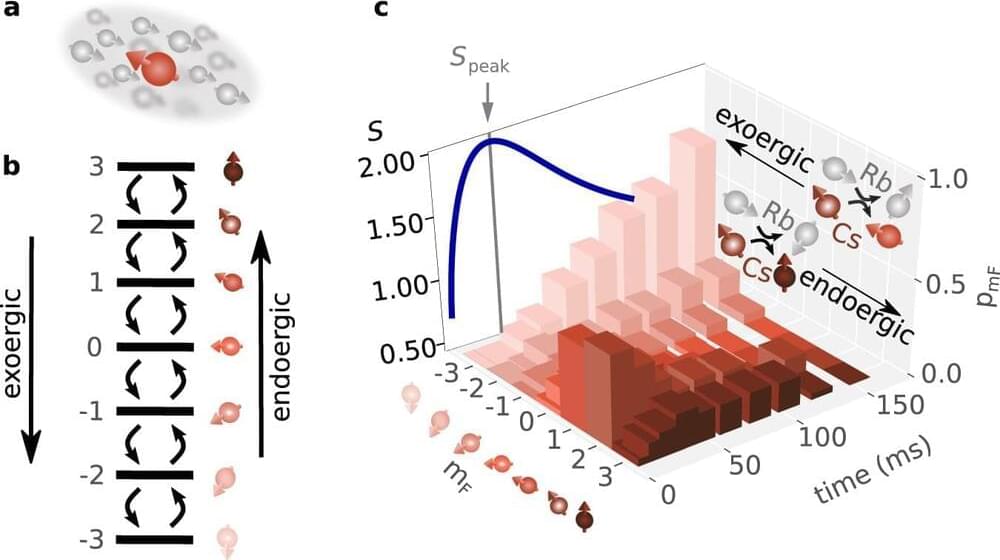

Universal behavior is a central property of phase transitions, which can be seen, for example, in magnets that are no longer magnetic above a certain temperature. A team of researchers from Kaiserslautern, Berlin and Hainan, China, has succeeded for the first time in observing such universal behavior in the temporal development of an open quantum system, a single cesium atom in a bath of rubidium atoms.

This finding helps to understand how quantum systems reach equilibrium. This is of interest to the development of quantum technologies, for example. The study has been published in Nature Communications.

Phase transitions in chemistry and physics are changes in the state of a substance, for example, the change from a liquid to a gaseous phase, when an external parameter such as temperature or pressure is changed.

💰Special Offer!💰 Use our link https://joinnautilus.com/SABINE to get 15% off your membership!Physicists have shattered previous limits of the new technolog…

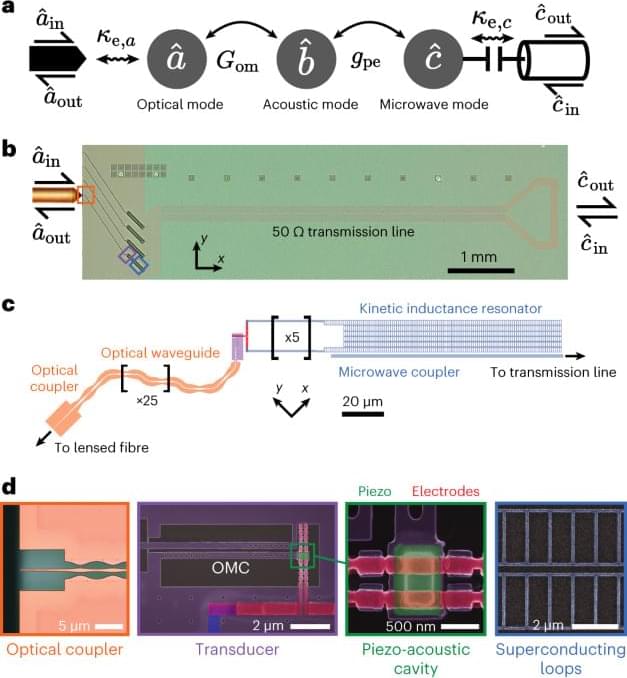

Generating quantum correlations between light and microwaves.

Non-classical microwave–optical photon pair generation with a chip-scale transducer.

A transducer that generates microwave–optical photon pairs is demonstrated. This could provide an interface between optical communication networks and superconducting quantum devices that operate at microwave frequencies.

The Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences (INI) in Cambridge hosted a research programme on one of the most pressing problems in modern physics: to build a theory that can explain all the fundamental forces and particles of nature in one unifying mathematical framework. Such a theory of quantum gravity would combine two hugely successful frameworks on theoretical physics, which have so far eluded unification: quantum physics and Einstein’s theory of gravity.

The Black holes: bridges between number theory and holographic quantum information programme focusses on black holes, which play a hugely important part in this area, on something called the holographic principle, and on surprising connections to pure mathematics. This collection of articles explores the central concepts involved and gives you a gist of the cutting edge research covered by the INI programme.

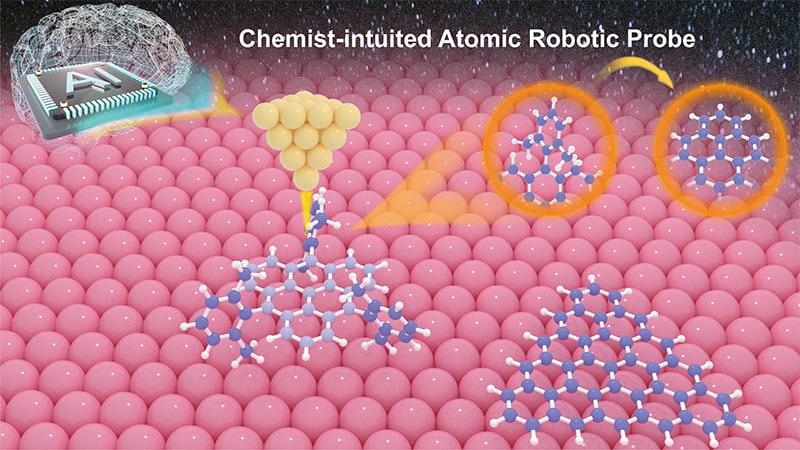

Scientists from the National University of Singapore (NUS) have pioneered a new methodology of fabricating carbon-based quantum materials at the atomic scale by integrating scanning probe microscopy techniques and deep neural networks. This breakthrough highlights the potential of implementing artificial intelligence (AI) at the sub-angstrom scale for enhanced control over atomic manufacturing, benefiting both fundamental research and future applications.

Open-shell magnetic nanographenes represent a technologically appealing class of new carbon-based quantum materials, which host robust π-spin centres and non-trivial collective quantum magnetism. These properties are crucial for developing high-speed electronic devices at the molecular level and creating quantum bits, the building blocks of quantum computers. Despite significant advancements in the synthesis of these materials through on-surface synthesis, a type of solid-phase chemical reaction, achieving precise fabrication and tailoring of the properties of these quantum materials at the atomic level has remained a challenge.

The figure illustrates the chemist-intuited atomic robotic probe that would allow chemists to precisely fabricate organic quantum materials at the single-molecule level. The robotic probe can conduct real-time autonomous single-molecule reactions with chemical bond selectivity, demonstrating the fabrication of quantum materials with a high level of control. (© Nature Synthesis)

Experiments demonstrate some of the unusual features of molecular reactions that occur in the deep cold of interstellar space.

Many common small molecules are formed in interstellar space, and their low temperatures are expected to have profound effects on their chemical reactions because of quantum-mechanical effects that are masked at higher temperatures. Researchers have now demonstrated some of these cold chemistry phenomena—such as the effects of molecular rotation and collision energy on reaction rates—in a reaction between a hydrogen ion and an ammonia molecule in the lab. The results, while intuitively surprising at first glance, can be explained by a careful theoretical analysis of the quantum chemistry.

Measuring reaction rates at low temperatures is useful for testing quantum-chemical theory because in those conditions molecules may occupy only a few well-defined quantum states. Such experiments could also offer insights into chemical processes in the cold clouds of gas in star-forming regions of interstellar space, where many of the simple molecules that make up solar systems are formed. But low-temperature experiments are difficult, especially for charged atoms and molecules (ions), because they are very sensitive to stray electric fields in the environment, which accelerate and heat up the ions.

Scientists at Rice University have uncovered a first-of-its-kind material: a 3D crystalline metal in which quantum correlations and the geometry of the crystal structure combine to frustrate the movement of electrons and lock them in place.

The find is detailed in a study published in Nature Physics. The paper also describes the theoretical design principle and experimental methodology that guided the research team to the material. One part copper, two parts vanadium, and four parts sulfur, the alloy features a 3D pyrochlore lattice consisting of corner-sharing tetrahedra.

Highly precise optical absorption spectra of diamond reveal ultra-fine splitting.

Besides being “a girl’s best friend,” diamonds have broad industrial applications, such as in solid-state electronics. New technologies aim to produce high-purity synthetic crystals that become excellent semiconductors when doped with impurities as electron donors or acceptors of other elements.

The Science of Doping.

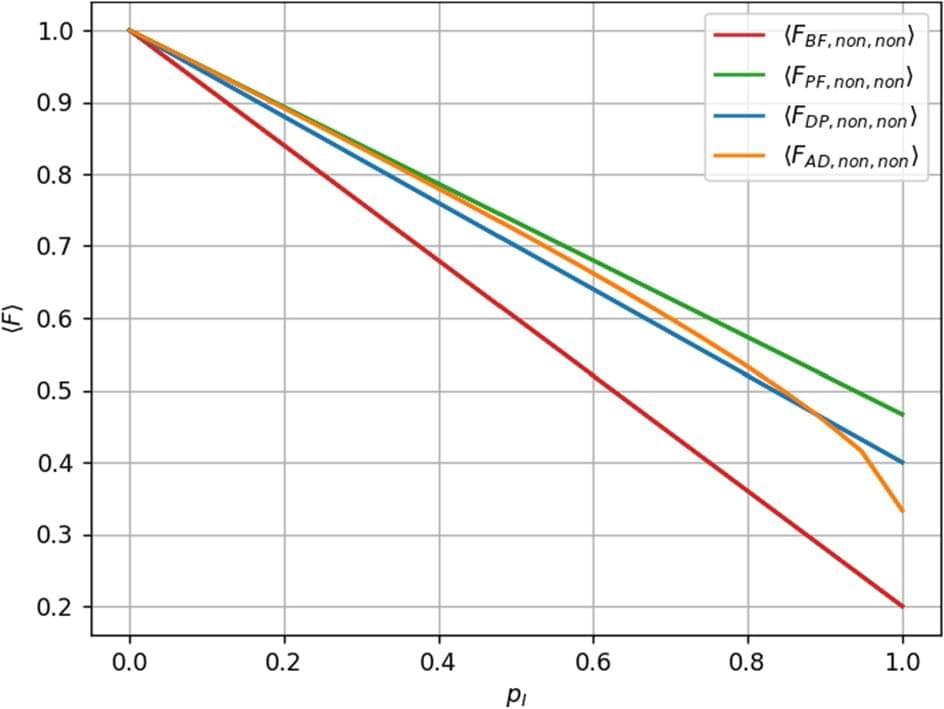

The four quantum noises-Bit Flip, Phase Flip, Depolarization, and Amplitude Damping-as well as any potential combinations of them, are examined in this paper’s investigation of quantum teleportation using qutrit states. Among the mentioned noises, we observed that phase flip has the highest fidelity. When compared to uncorrelated Amplitude Damping, we find that Correlated Amplitude Damping performs two times better. Finally, we conclude that for better fidelity, it is preferable to introduce the same noise in channel state if noise is unavoidable.