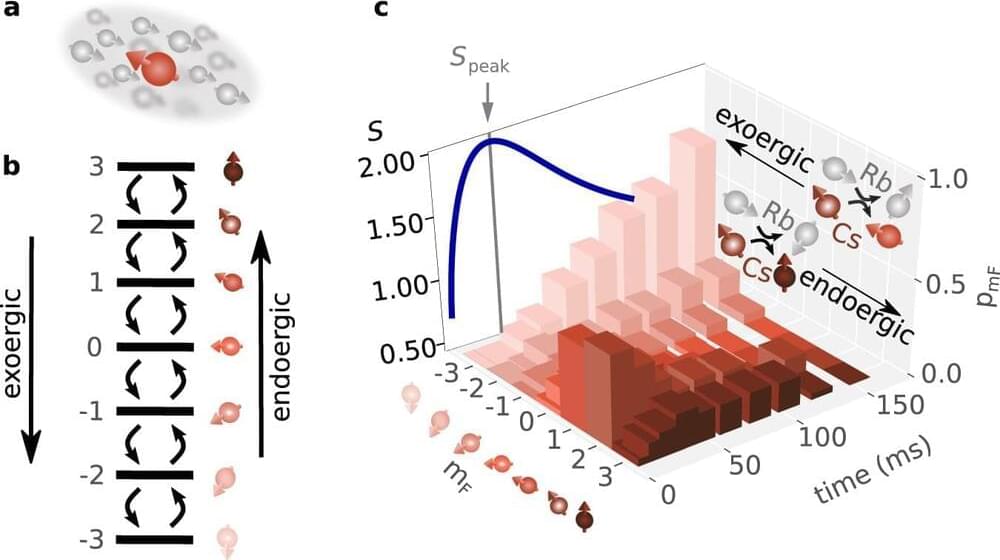

Universal behavior is a central property of phase transitions, which can be seen, for example, in magnets that are no longer magnetic above a certain temperature. A team of researchers from Kaiserslautern, Berlin and Hainan, China, has succeeded for the first time in observing such universal behavior in the temporal development of an open quantum system, a single cesium atom in a bath of rubidium atoms.

This finding helps to understand how quantum systems reach equilibrium. This is of interest to the development of quantum technologies, for example. The study has been published in Nature Communications.

Phase transitions in chemistry and physics are changes in the state of a substance, for example, the change from a liquid to a gaseous phase, when an external parameter such as temperature or pressure is changed.