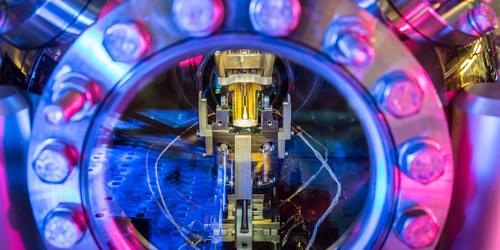

A future quantum network of optical fibers will likely maintain communication between distant quantum computers. Sending quantum information rapidly across long distances has proved difficult, in part because most photons don’t survive the trip. Now Viktor Krutyanskiy of the University of Innsbruck, Austria, and his colleagues have more than doubled the success rate for sending photons that are quantum mechanically entangled with atoms to a distant site [1]. Instead of the previous approach of sending photons one at a time and waiting to see if each one arrives successfully, the researchers sent photons in groups of three. They believe that sending photons in larger numbers should be feasible in the future, allowing much faster transmission of quantum information.

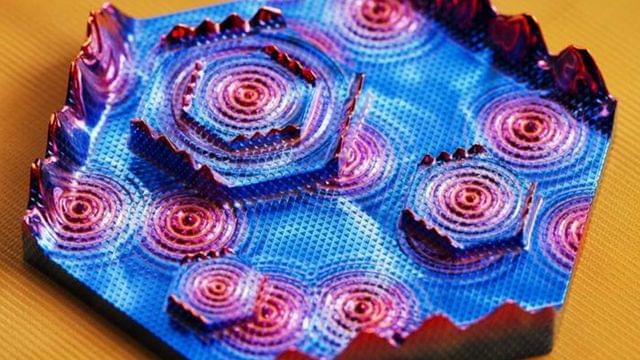

Quantum networks require entanglement distribution, which involves sending a photon entangled with a local qubit to a distant location. The distribution system must check for the arrival and for the entanglement of each photon at the remote site before another attempt can be made, which can be time consuming. For a 100-km-long fiber, the light travel time combined with losses in the fiber and other inefficiencies limit the rate for this process to about one successful photon transfer per second using state-of-the-art equipment.

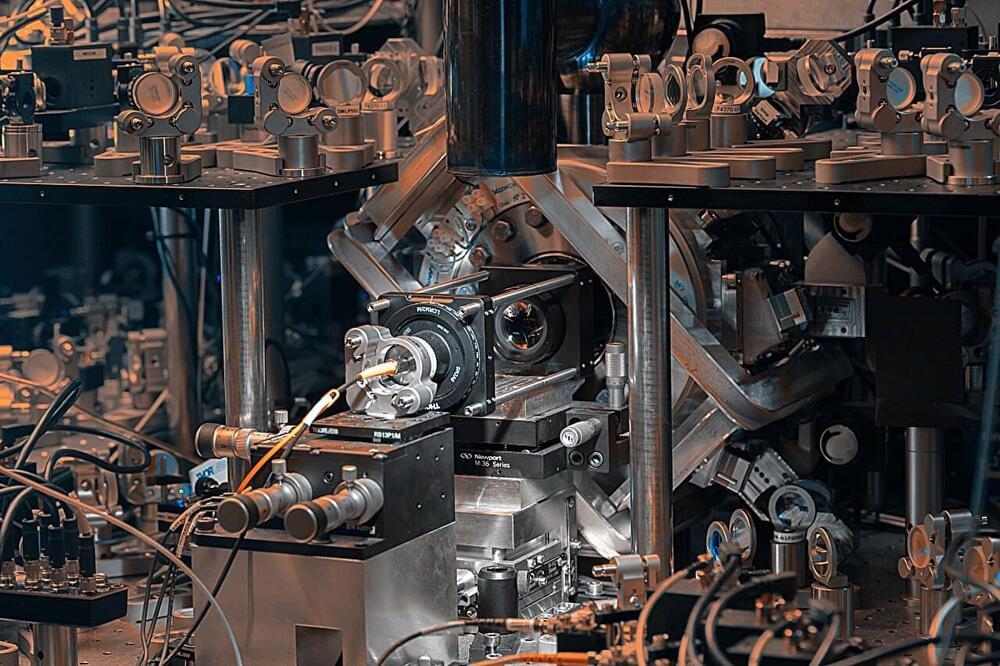

For faster distribution, Krutyanskiy and his colleagues trapped three calcium ions (qubits) in an optical cavity and performed repeated rounds of their protocol: in rapid sequence, each ion was triggered to emit an entangled photon that was sent down a 101-km-long, spooled optical fiber. In one experiment, the team performed nearly 900,000 of these “attempts,” detecting entangled photons at the far end 1906 times. The effective success rate came out to 2.9 per second. The team’s single-ion success rate was 1.2 per second.