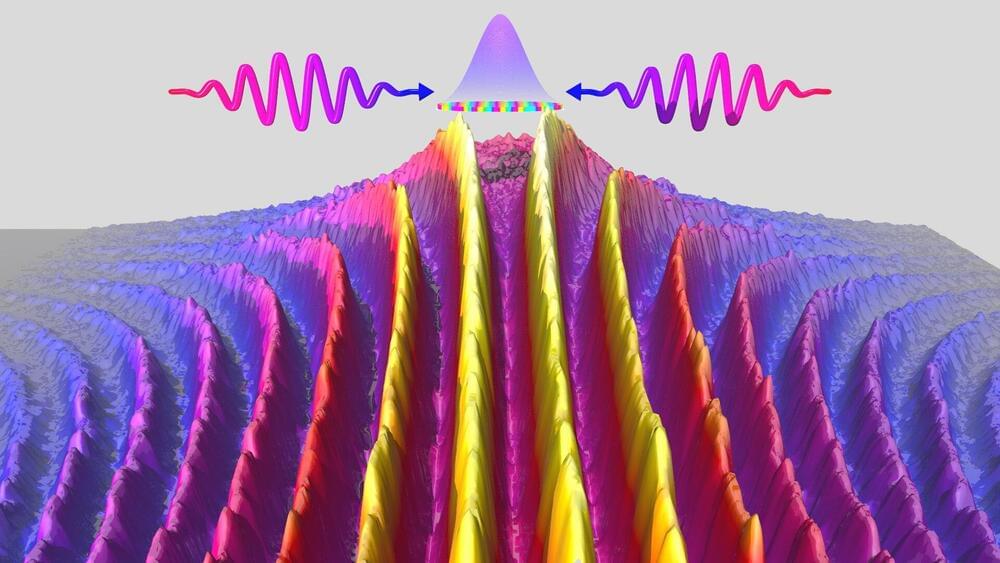

A way to create single photons whose spatiotemporal shapes do not expand during propagation could limit information loss in future photonic quantum technologies.

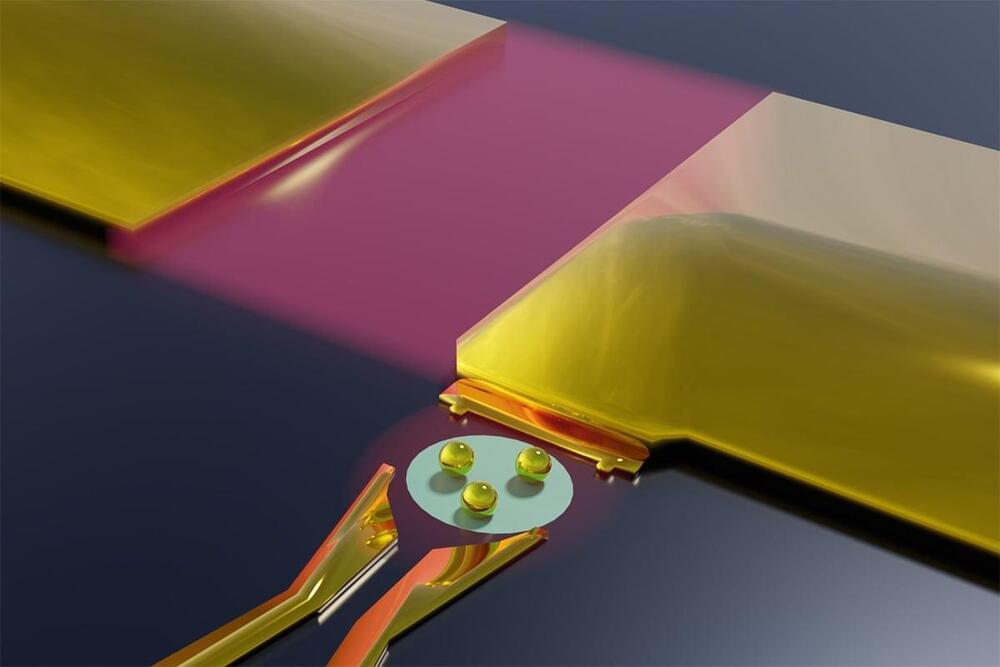

When enjoying the sight of a rainbow, information loss might not be the first thing that comes to mind. Yet dispersion, the underlying process that makes different colors travel at different speeds, also hampers scientists’ control of light propagation—a crucial capability for future photonic quantum technologies. As they move, short laser pulses tend to lengthen through dispersion and widen and dim through diffraction. Together, these effects limit our ability to make light reach a target, although mitigation strategies have been developed for classical pulses and, recently, for quantum light. Now Jianmin Wang at the Southern University of Science and Technology in China and colleagues have realized a quantum source of single photons that are impervious to spreading out during propagation, potentially safeguarding against the loss of information encoded in the photons spatiotemporal shapes [1].

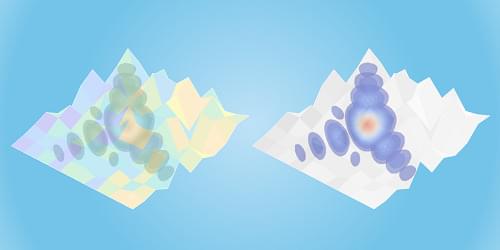

In 2007, physicists demonstrated light beams, known as Airy beams, whose spatial profiles make them resilient to spreading out [2, 3]. These profiles consist of a pattern of bright and dark lobes surrounding a central bright component, with each feature propagating along a parabolic trajectory. Recently, scientists created quantum Airy beams, which are technically challenging to realize [4, 5]. The goal of Wang and colleagues’ work was to extend this principle to the temporal domain, producing quantum Airy single photons that do not spread out in both space and time. Such quantum “light bullets” could offer exciting possibilities for quantum technologies, much like their classical counterparts did for applications in areas from plasma physics to optical trapping [3, 6].