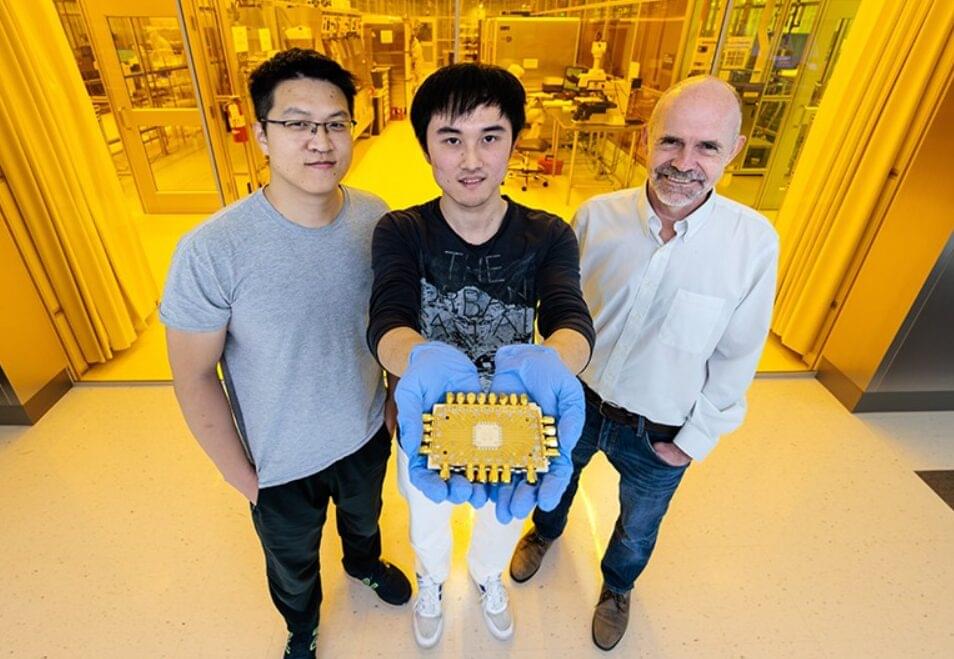

A groundbreaking step in quantum technology has been achieved with the demonstration of an integrated spin-wave quantum memory, overcoming challenges of photon transmission loss and noise suppression.

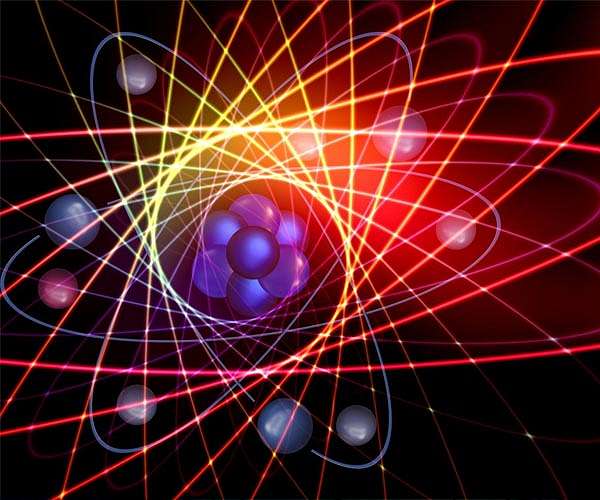

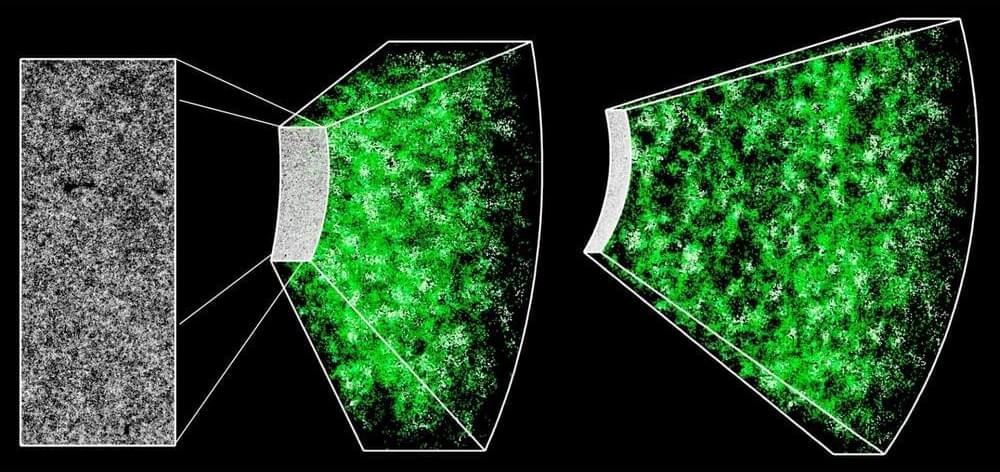

Quantum memories play a crucial role in creating large-scale quantum networks by enabling the connection of multiple short-distance entanglements into long-distance entanglements. This approach helps to overcome photon transmission losses effectively. Rare-earth ion-doped crystals are a promising candidate for implementing high-performance quantum memories, and integrated solid-state quantum memories have already been successfully demonstrated using advanced micro-and nano-fabrication techniques.

Limitations of Existing Quantum Memory.