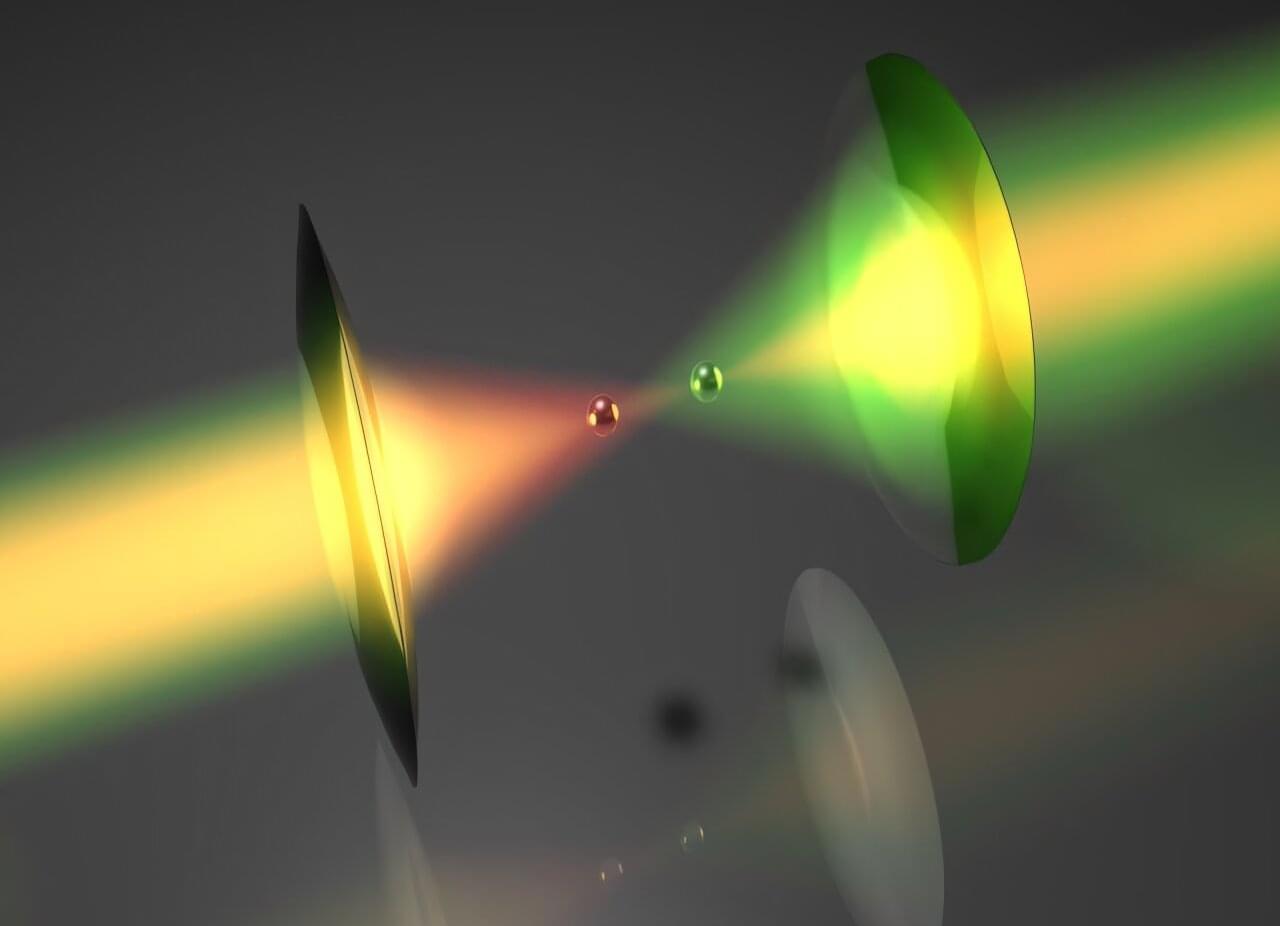

An article published in the journal Optica describes the development of a new experimental device that explores the boundary between classical and quantum physics, allowing the simultaneous observation and investigation of phenomena from both worlds.

The instrument was developed in Florence and is the result of collaboration within the extended partnership of the National Quantum Science and Technology Institute (NQSTI), involving the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Florence, the National Institute of Optics of the National Research Council (CNR-INO), as well as the European Laboratory for Nonlinear Spectroscopy (LENS) and the Florence branch of the National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN).

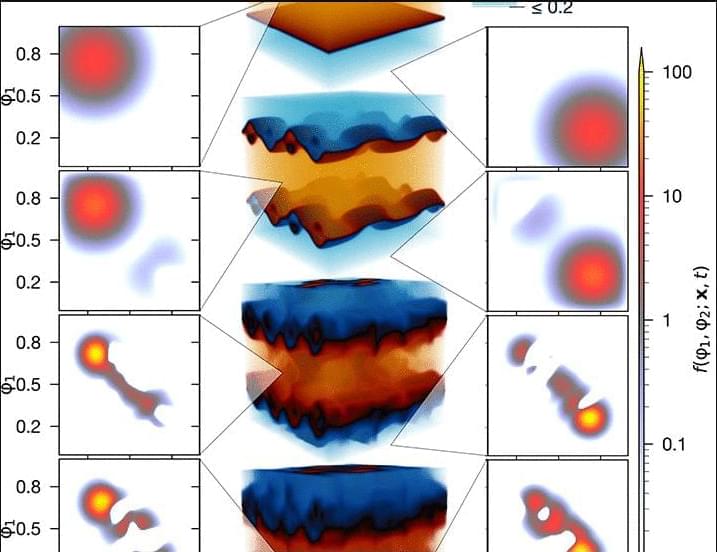

It is well known that the study of matter, as we progress to increasingly smaller scales, shows radically different behaviors from those observed at the macroscopic scale: this is where quantum physics comes into play, helping to understand the properties of matter in the world of the infinitely small. While these phenomena have been studied separately until now, the instrument developed by CNR-INO researchers allows for the experimental exploration of matter’s behavior from both perspectives.