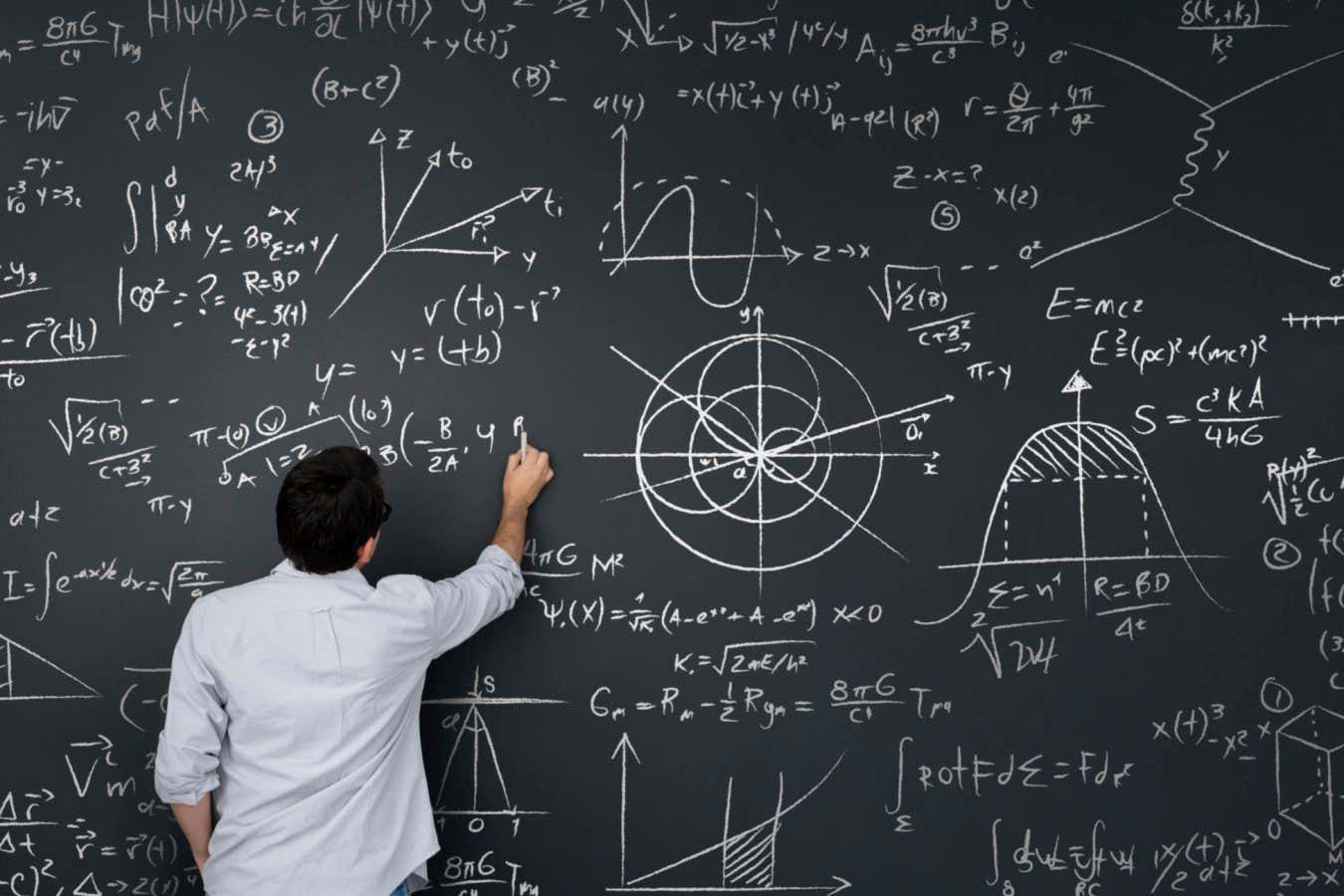

AI gives a thumbs up to Brett Bellmore innovative modifications to Robert Zubrin’s Nuclear Salt Water Rocket (NSWR). Switching from water to polyethene and storing in sausage strings could enhance its performance and safety, particularly focusing on avoiding criticality during storage, minimizing parasitic mass, and addressing practical challenges like micrometeorite protection and fuel state.

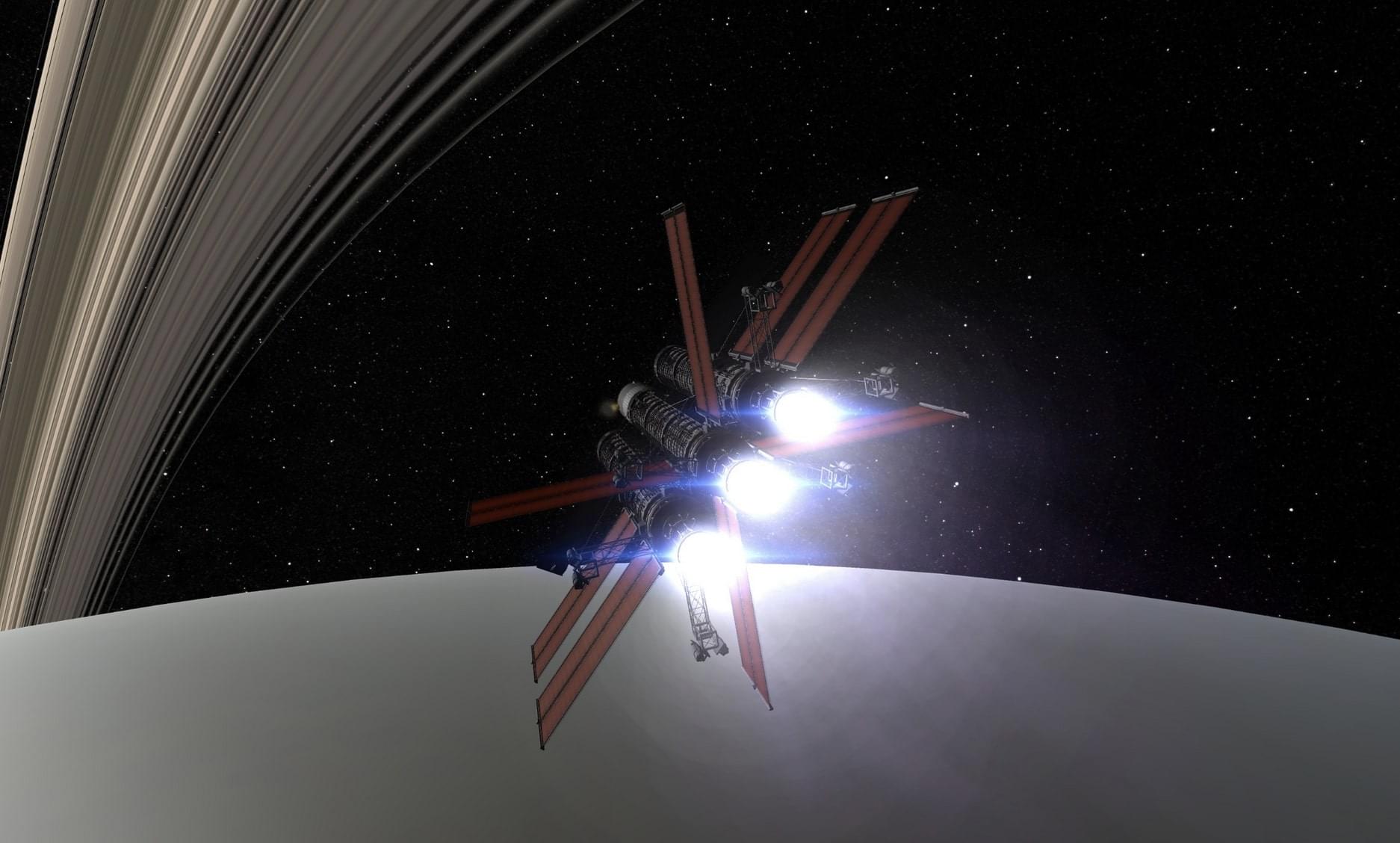

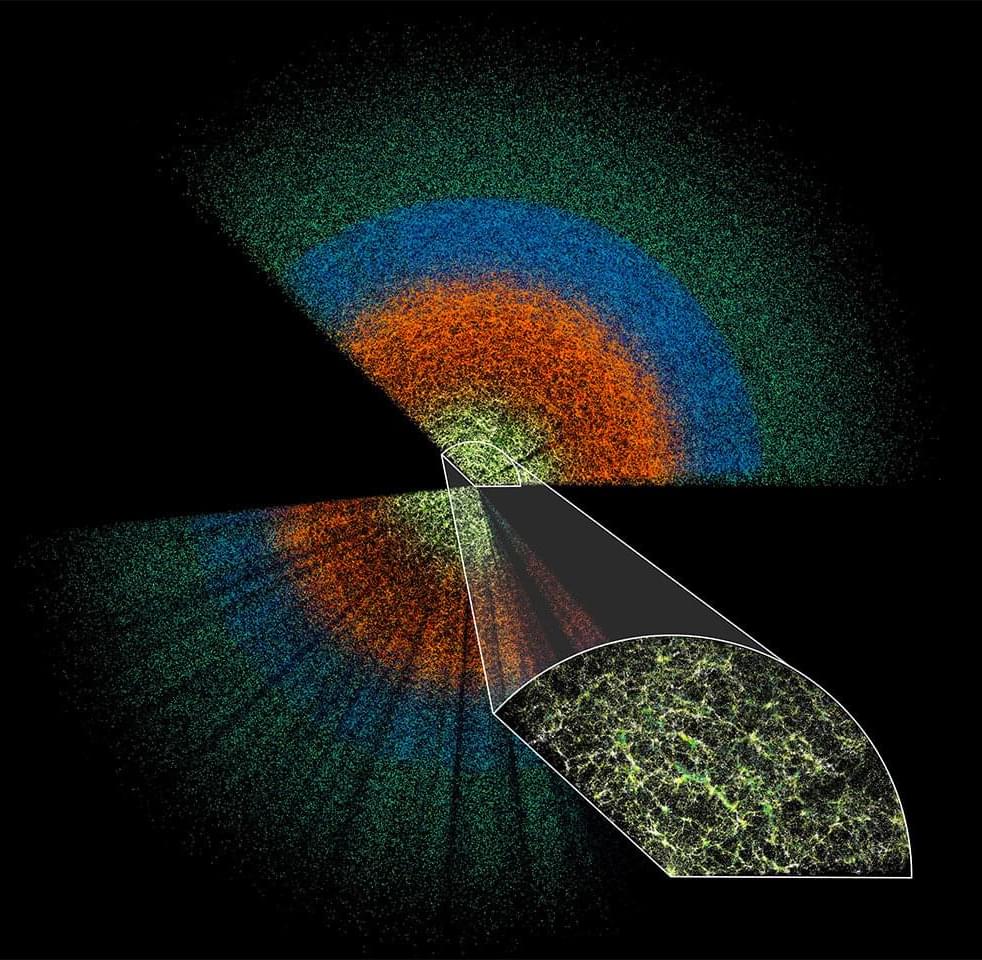

Robert Zubrin’s Nuclear Salt Water Rocket (NSWR) design is a rocket that uses known physics and engineering. My previous analysis shows that the first working prototype might be made in space with a 10–20 year development program for 10–30 billion. There are versions that could reach 7–8% of light speed. The use of low grade uranium enrichment for a more near term version is the one that is often described. However, if weapons grade uranium (90% enrichment) is used then he exhaust would be at 1.575% of the speed of light. A 30,000 ton ice asteroid and 7,500 tons of uranium could propel a 300 ton payload including a crew to 7.62% of light speed.

One of key parts of the engineering is to use water to protect the nozzle from the intense heat of the system. A combination of the coatings and space between the pipes would prevent the solution from reaching critical mass until it was pumped into a reaction chamber. It would reach critical mass and it being expelled through a nozzle to generate thrust. The nozzle would be protected by running water.