A new AI program observed physical phenomena and uncovered relevant variables—a necessary precursor to any physics theory.

Category: physics – Page 222

An AI May Have Just Invented “Alternative” Physics

An AI shown videos of physical phenomena and instructed to identify the variables involved produced answers different from our own.

Artificial Intelligence Discovers Alternative Physics

A new Columbia UniversityColumbia University is a private Ivy League research university in New York City that was established in 1754. This makes it the oldest institution of higher education in New York and the fifth-oldest in the United States. It is often just referred to as Columbia, but its official name is Columbia University in the City of New York.

Roboticists discover alternative physics

Energy, mass, velocity. These three variables make up Einstein’s iconic equation E=MC2. But how did Einstein know about these concepts in the first place? A precursor step to understanding physics is identifying relevant variables. Without the concept of energy, mass, and velocity, not even Einstein could discover relativity. But can such variables be discovered automatically? Doing so could greatly accelerate scientific discovery.

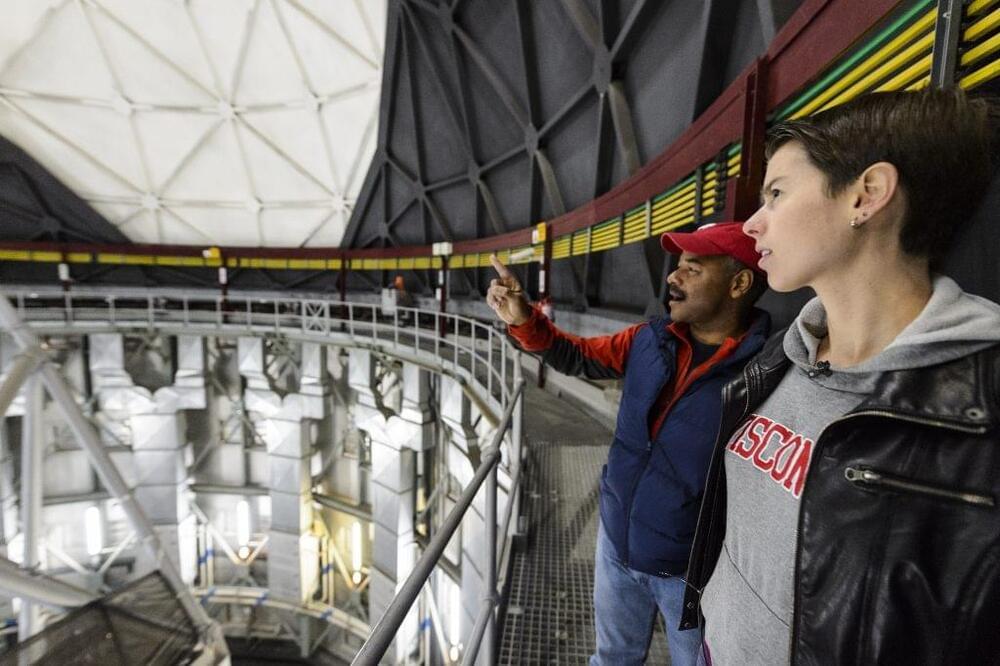

This is the question that researchers at Columbia Engineering posed to a new AI program. The program was designed to observe physical phenomena through a video camera, then try to search for the minimal set of fundamental variables that fully describe the observed dynamics. The study was published on July 25 in Nature Computational Science.

The researchers began by feeding the system raw video footage of phenomena for which they already knew the answer. For example, they fed a video of a swinging double pendulum known to have exactly four “state variables”—the angle and angular velocity of each of the two arms. After a few hours of analysis, the AI produced the answer: 4.7.

Physics, Life Sciences, and Dragon Cargo Transfer Top Tuesday’s Task List for Crew

The Expedition 67 crewmembers aboard the International Space Station spent Tuesday predominantly on research, maintenance, and cargo transfer operations.

Research beneficial to humans on Earth and future crews in space is happening around the clock aboard the orbiting laboratory. NASA Flight Engineer Kjell Lindgren used a majority of his day to service samples for the Immunosenescence investigation inside the Life Science Glovebox. Results from this study may one day inform treatments for accelerated aging processes commonly observed in microgravity and contribute to countermeasures for normal aging progression.

Kinetic energy: Newton vs. Einstein | Who’s right?

Using Newtonian physics, physicists have found an expression for the value of kinetic energy, specifically KE = ½ m v^2. Einstein came up with a very different expression, specifically KE = (gamma – 1) m c^2. In this video, Fermilab’s Dr. Don Lincoln shows how these two equations are the same at low energy and how you get from one to the other.

Relativity playlist:

Fermilab physics 101:

https://www.fnal.gov/pub/science/particle-physics-101/index.html.

Fermilab home page:

https://fnal.gov

Astronomers find ‘Goldilocks’ black hole

Last year, scientists used gravitational waves to detect an elusive intermediate-mass black hole for the first time. Now, Australian astronomers have spotted another – this time using gamma-ray bursts.

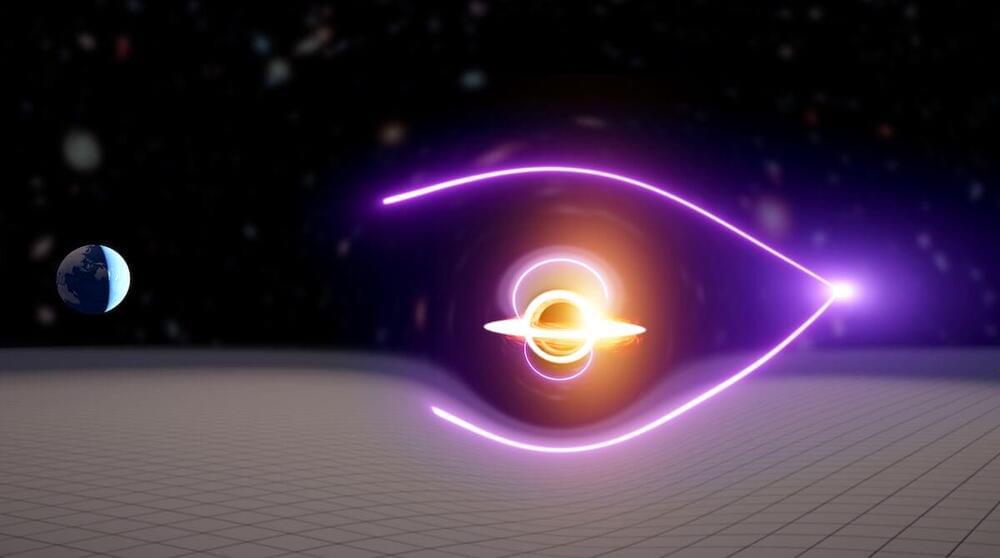

Black holes are formed when massive stars reach the end of their lives and collapse under their own gravity. But they aren’t all the same – stellar mass black holes are small, just a few times the mass of our Sun, while supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxy are enormous, with masses millions or even billions of times greater than our sun.

Intermediate mass black holes are the missing link between these two populations, thought to span between 100 and 100,000 solar masses. The black hole discovered in 2020 was 142 solar masses – while this newly discovered monster is on the other end of the scale, at approximately 55,000 solar masses.

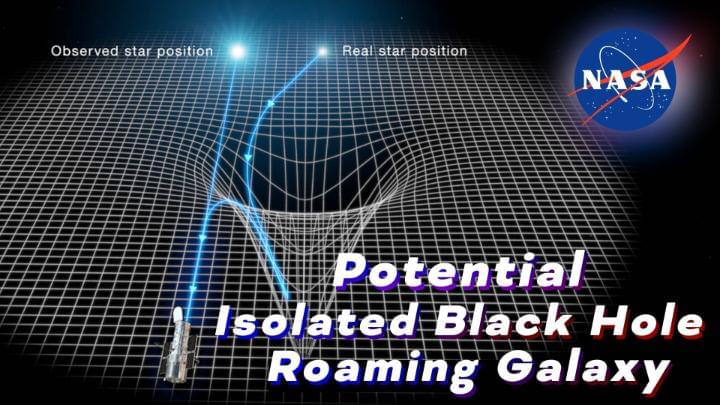

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope

It’s estimated that about 100 million black holes roam around our Milky Way Galaxy — and for the first time ever, astronomers now believe they may have precisely measured the mass of an isolated black hole with Hubble.

Roaming black holes are born from rare, monstrous stars that are at least 20 times more massive than our Sun. After these stars explode in a supernova, the remnant core is crushed by gravity into a black hole. Because this self-detonation isn’t perfectly symmetrical, the black hole might get “kicked” and careen through our galaxy.

Astronomers believe that the isolated black hole measured by Hubble is traveling across the Milky Way at 100,000 miles per hour (160,000 kph). That’s fast enough to get from Earth to the Moon in less than three hours!

Read more about this discovery: https://go.nasa.gov/3mx6t6p.

#NASA #Hubble #BlackHole #astronomy #science #universe #astrophysics #space #stars #galaxy

View insights.