On Tuesday, July 5, space physics and human studies dominated the science agenda aboard the International Space Station. The Expedition 67 crew also reconfigured a US airlock and put a new 3D printer through its paces.

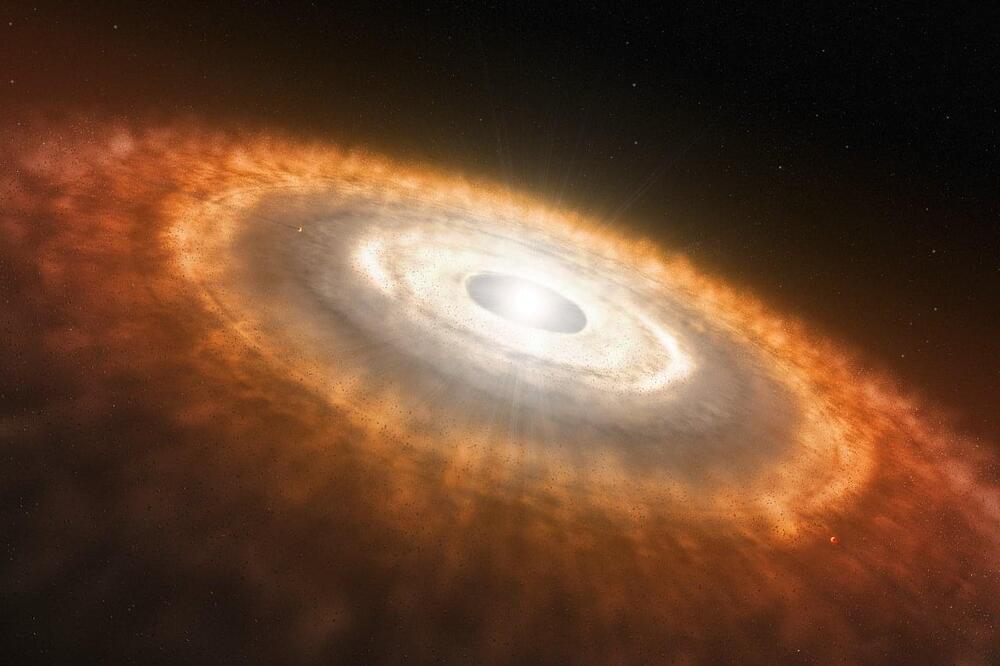

The lack of gravity in space impacts a wide range of physics revealing new phenomena that researchers are studying to improve life for humans on and off the Earth. One such project uses artificial intelligence to adapt complicated glass manufacturing processes in microgravity with the goal of benefitting numerous Earth-and space-based industries. On Tuesday afternoon, NASA

Established in 1958, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is an independent agency of the United States Federal Government that succeeded the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). It is responsible for the civilian space program, as well as aeronautics and aerospace research. Its vision is “To discover and expand knowledge for the benefit of humanity.” Its core values are “safety, integrity, teamwork, excellence, and inclusion.”