The tech industry has more power than ever before. It’s time to leverage it to create real social, environmental, and political change. property= description.

Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer (left to right)

In 1911, Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, in his quest to study materials at ever lower temperatures, happened to find that the electrical resistance of some metallic materials suddenly vanished at temperatures near absolute zero. He called the phenomenon superconductivity, and scientists soon found additional materials that exhibited this property.

But no one could completely explain how it worked. For the next few decades, many prominent physicists worked to develop a theory of the mechanism underlying superconductivity, but no one had much success, and some despaired of figuring it out. One such physicist, Felix Bloch, was quoted as proposing “Bloch’s theorem: Superconductivity is impossible.”

It’s a basic rule of chemistry and physics: when you heat things up, they get bigger. While there are exceptions (like water and ice), it’s difficult to find a material with zero thermal expansion.

But new research from the University of New South Wales and the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation has found a compound that doesn’t thermally expand – at least, not between −269°C and 1126°C.

The researchers examined a substance made from scandium, aluminium, tungsten and oxygen (Sc1.5 Al0.5 W3 O12), bonded together in a crystalline structure.

In a new world record, China’s “artificial sun” project has sustained a nuclear fusion reaction for more than 17 minutes, reports Anthony Cuthbertson for the Independent. In the latest experiment, superheated plasma reached 126 million degrees Fahrenheit—that’s roughly five times hotter than the sun, which radiates a scorching 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit at the surface and about 27 million degrees Fahrenheit at its core.

Coal and natural gas are the primary energy sources currently used around the world, but these materials come in limited supply. Nuclear fusion could be the cleanest energy source available because it replicates the sun’s physics by merging atomic nuclei to generate large amounts of energy into electricity. The process requires no fossil fuels, leaves behind no radioactive waste, and is a safer alternative to fission nuclear power, per the Independent.

“The recent operation lays a solid scientific and experimental foundation towards the running of a fusion reactor,” says Gong Xianzu, a researcher at the Institute of Plasma Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, in a statement.

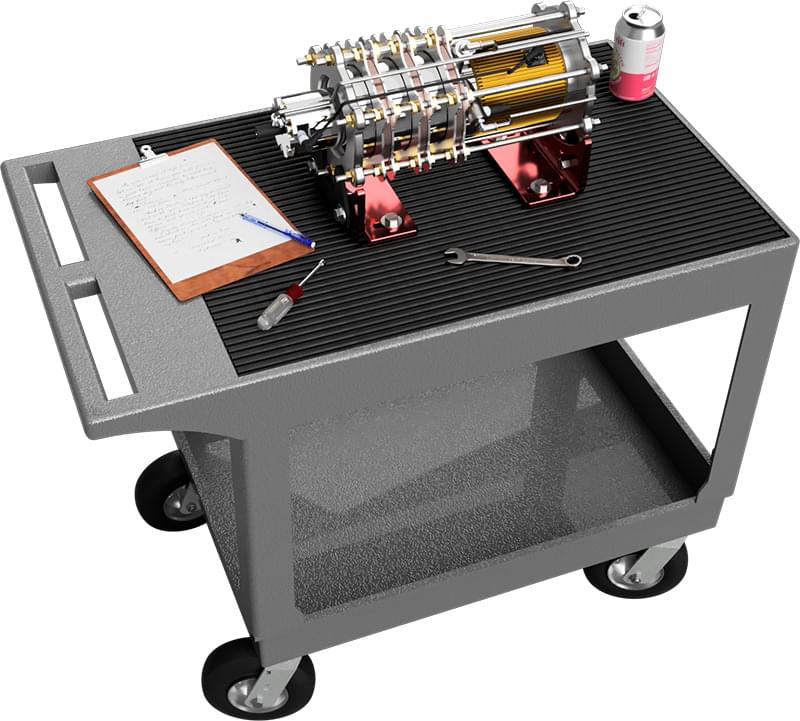

Avalanche is a VC-backed, fusion energy start-up based in Seattle, WA. They are designing, testing and building micro-fusion reactors that you can hold in your hand. Their modular reactor design can be stacked for endless power applications and unprecedented energy density to provide clean energy and decarbonize the planet.

Avalanche is developing a 5kWe power pack called the “Orbitron” in a form-factor the size of a lunch pail. The unique physics of the Orbitron allows for its compact size which is a key enabler for development, scaling, and a wide variety of applications. Avalanche Energy uses electrostatic fields to trap fusion ions and also uses a magnetron electron confinement to reach higher ion densities. The resulting fusion reaction produces neutrons that can be transformed into heat.

The magnetron is a variation of a component in regular microwave ovens and the electrostatic base technology is a derivative of a product available from ThermoFisher Scientific, which is widely deployed for use in commercial mass spectrometry. They are taking two devices that exist already, things you can buy commercially for various applications. They are putting them together in a new interesting way at much higher voltages” to build a “recirculating beam fusion” prototype.

A recent study from the Singapore Centre for Environmental Life Sciences Engineering (SCELSE) at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) and published in Wa | Chemistry And Physics.

This study is intriguing since one of the results of climate change is increasing water temperatures, so removing phosphorus from such waters will prove invaluable in the future, with this study appropriately being referred to as a “future-proof” method.

Since phosphorus in fresh water often results in algal blooms, removing it from wastewater prior to it being released into fresh water is extremely important. This is because algal blooms drastically reduce oxygen levels in natural waters when the algae die, often resulting in the delivery of high levels of toxins, killing organisms in those waters.

While traditional removal methods result in a large volume of inert sludge that requires treatment and disposal afterwards, this new SCELSE-developed method does not involve chemicals, most notably iron and aluminum coagulants. Using this new method, the research team was successful in removing phosphorus from wastewater at 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) and 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit).

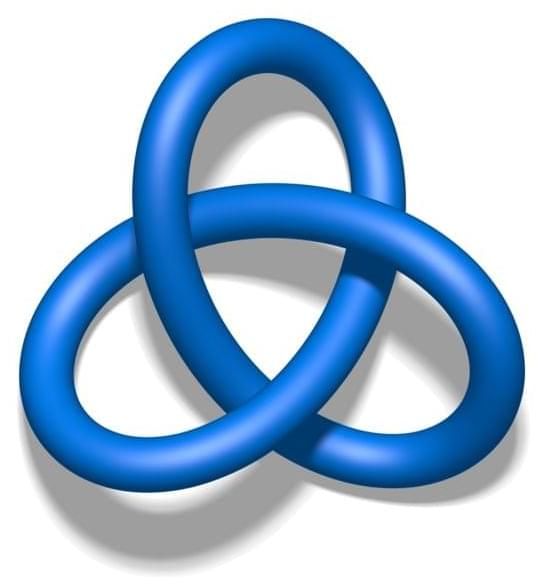

At the heart of every resonator—be it a cello, a gravitational wave detector, or the antenna in your cell phone—there is a beautiful bit of mathematics that has been heretofore unacknowledged.

Yale physicists Jack Harris and Nicholas Read know this because they started finding knots in their data.

In a new study in the journal Nature, Harris, Read, and their co-authors describe a previously unknown characteristic of resonators. A resonator is any object that vibrates only at a specific set of frequencies. They are ubiquitous in sensors, electronics, musical instruments, and other devices, where they are used to produce, amplify, or detect vibrations at specific frequencies.

Circa 2010

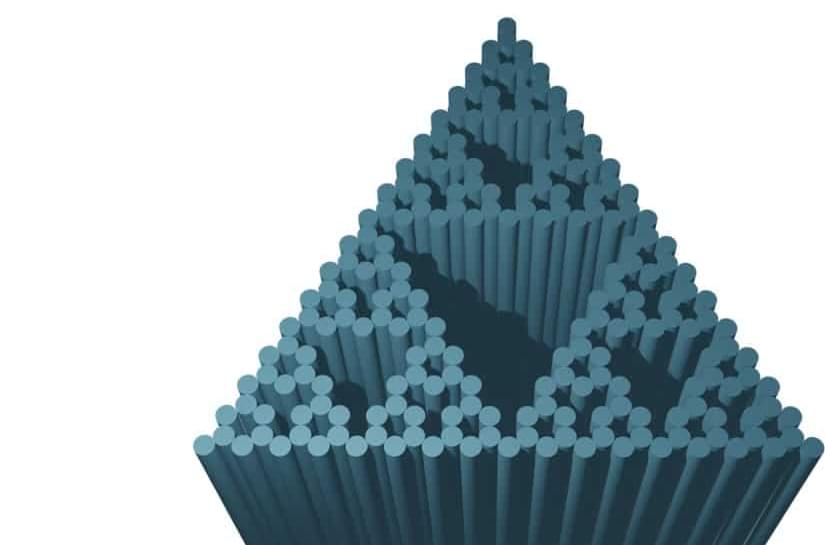

How do Utricularia, aquatic carnivorous plants commonly found in marshes, manage to capture their preys in less than a millisecond? A team of French physicists from the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire de Physique has identified the ingenious mechanical process that enables the plant to ensnare any small, a little too curious aquatic animals that venture too closely. It is the reversal of its curvature and the release of the associated elastic energy that make it the fastest known aquatic trap in the world. These results are published on 16 February 2011 on the website of the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B.

Utricularia are carnivorous plants that capture small prey with remarkable suction traps. Utricularia are rootless plants formed of very thin, forked leaves on which wineskin-shaped traps, just a few millimeters in size, are attached. Only the flowers, standing on long stems, stick out of the water. The traps are underwater. When an aquatic animal (water fleas, cyclops, daphnia or small mosquito larvae) touches its sensitive hairs, the trap sucks it in, in a fraction of a second, along with water, which is then drained through its walls.

In order to understand the mechanical process involved, the researchers observed and recorded the extremely rapid movements of the capture phase with a high speed camera. The scientists show that the trap door buckles, which reverses its curvature and allows it to open and close very rapidly, thus entrapping its prey. The suction time (less than a millisecond) is much shorter than was previously assumed.