In the early 1900s, Albert Einstein proposed the theory of general relativity, which challenged everything scientists believed they understood about the universe at the time. Over the years, scientists have questioned whether this theory was true. However, a newly created dark matter map finally gives undeniable proof.

We must first look at Einstein’s original theory to fully understand this new development. Before Einstein proposed the theory of general relativity, scientists believed space to be almost featureless and changeless. Further, they thought that time flowed at its own pace, oblivious to clocks that tried to measure it, as Isaac Newton had suggested two centuries earlier.

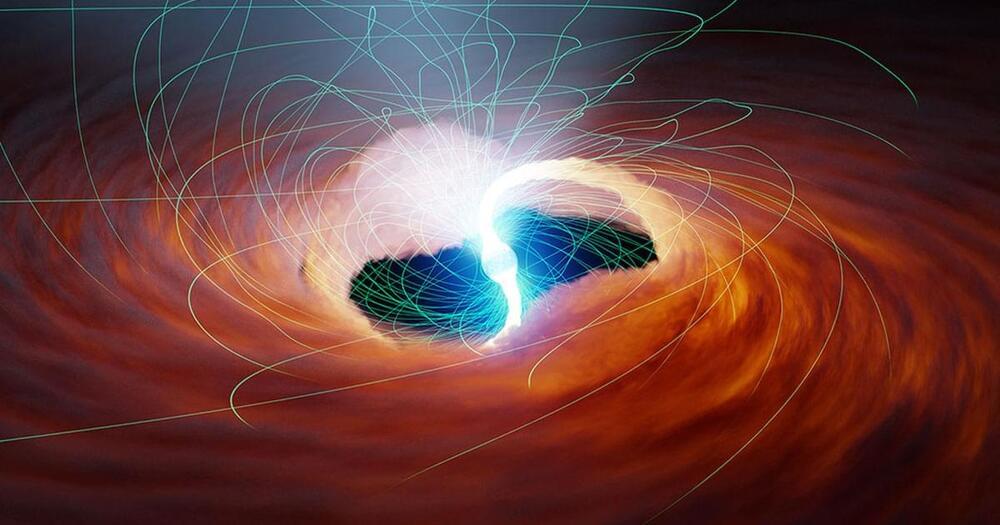

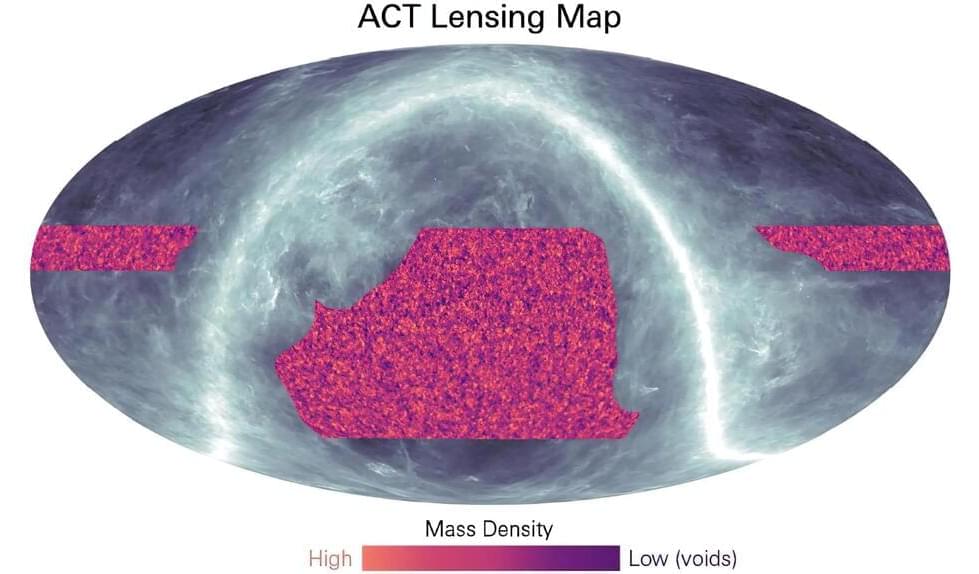

However, Einstein proposed that both space and time were one force, spacetime, and that matter within this ever-changing stage was controlled by the curving path that gravity dictated. But to create gravity, we needed mass, a force so strong it could literally curve spacetime around it. This is where dark matter comes into play.