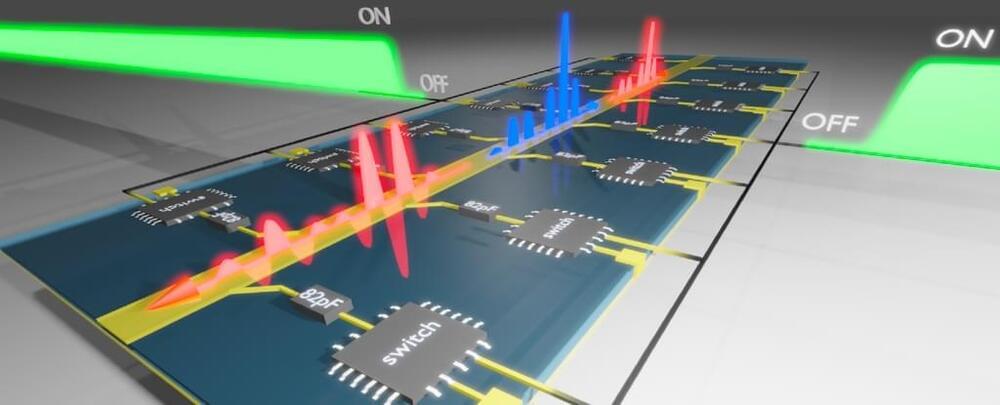

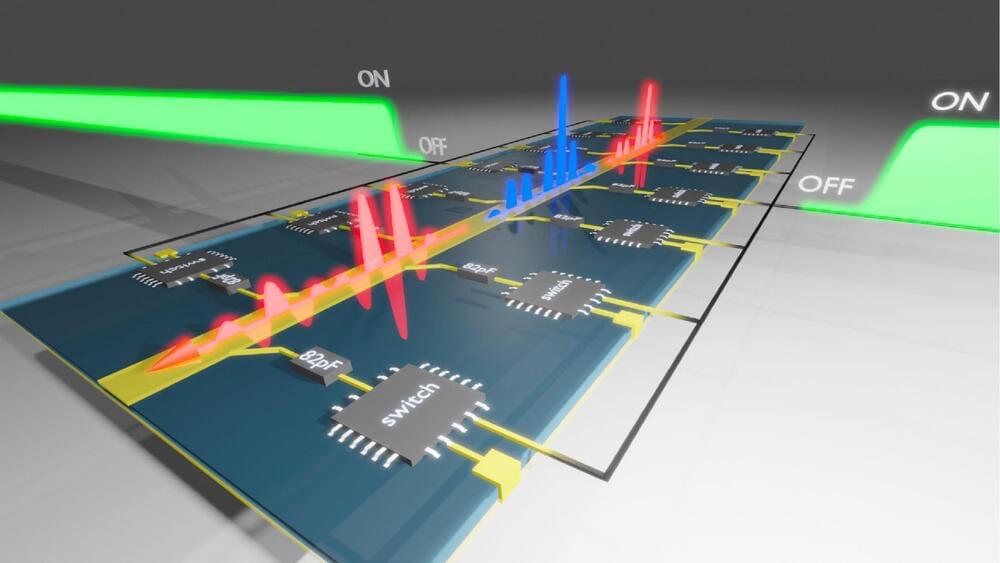

It’s a theoretical concept, but realistic enough that NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts program has given Davoyan’s group $175,000 to show that the technology is feasible. “There’s rich physics in there,” says Davoyan, a mechanical and aerospace engineer at UCLA. To create propulsion, he continues, “you either throw the fuel out of the rocket or you throw the fuel at the rocket.” From a physics perspective, they work the same: Both impart momentum to a moving object.

His team’s project could transform long-distance space exploration, dramatically expanding the astronomical neighborhood accessible to us. After all, we’ve only sent a few robotic visitors to scope out Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and their moons. We know even less about objects lurking farther away. The even smaller handful of NASA craft en route to interstellar space include Pioneer 10 and 11, which blasted off in the early 1970s; Voyager 1 and 2, which were launched in 1977 and continue their mission to this day; and the more recent New Horizons, which took nine years to fly by Pluto in 2015, glimpsing the dwarf planet’s now famous heart-shaped plain. Over its 46-year journey, Voyager 1 has ventured farthest from home, but a pellet-beam-powered craft could overtake it in just five years, Davoyan says.

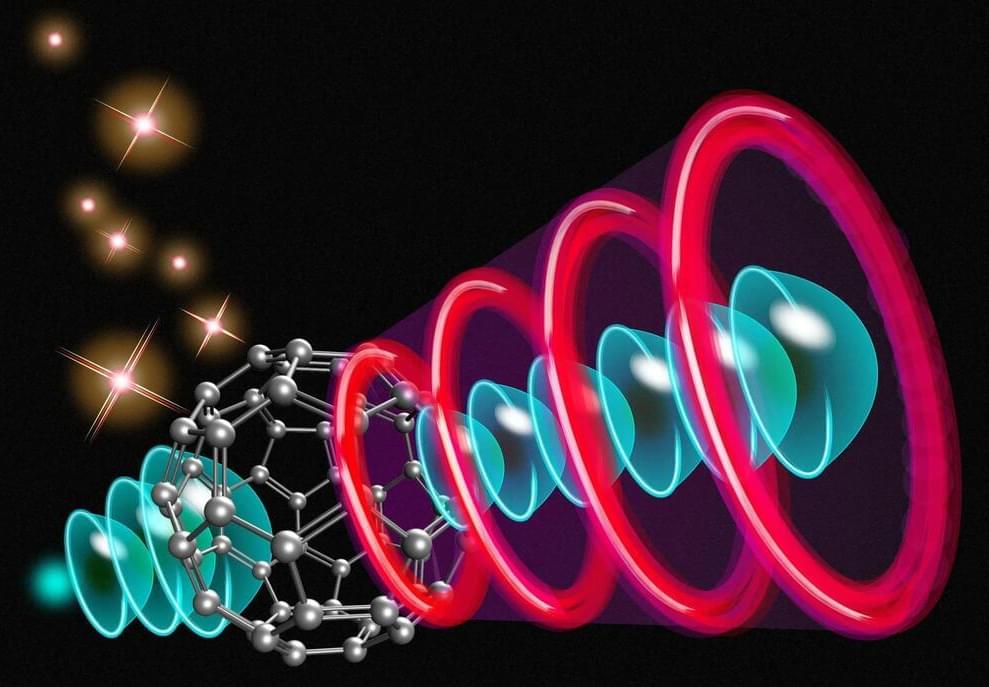

He takes inspiration from Breakthrough Starshot, a $100 million initiative announced in 2016 by Russian-born philanthropist Yuri Milner and British cosmologist Stephen Hawking to use a 100-gigawatt laser beam to blast a miniature probe toward Alpha Centauri. (The star nearest our solar system, it resides “only” 4 light-years away.) The Starshot team is exploring how they could hurl a 1-gram craft attached to a lightsail into interstellar space, using the laser to accelerate it to 20 percent of the speed of light, which is ludicrously fast and would reduce travel time from millennia to decades. “I’m increasingly optimistic that later this century, humanity’s going to be including nearby stars in our reach,” says Pete Worden, Breakthrough Starshot’s executive director.