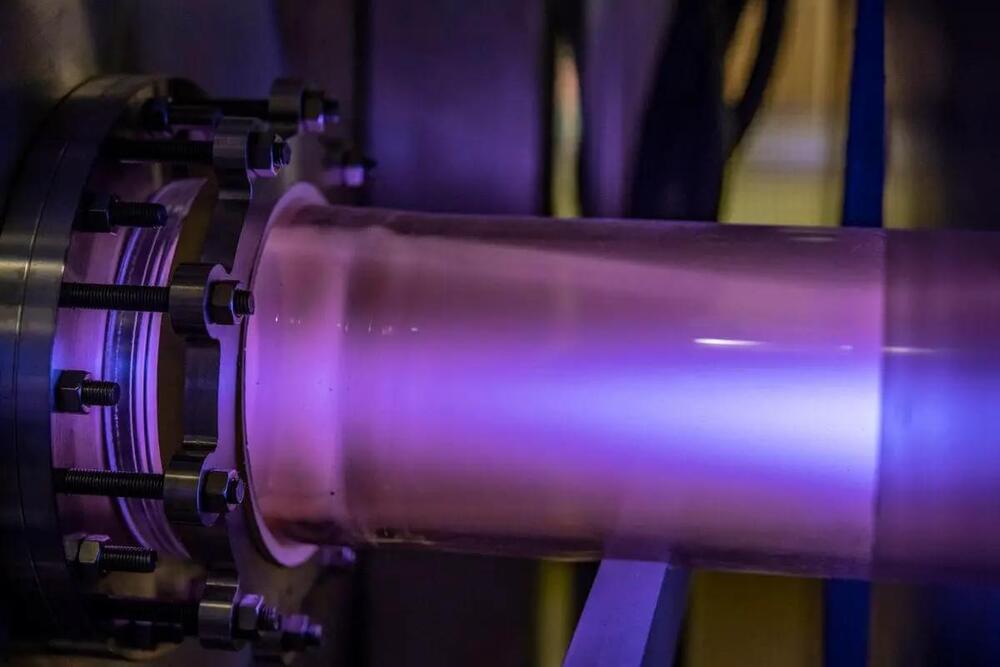

In 2018, a team of scientists at the University of California, Santa Barbara proposed a method for creating Kerr-Newman black holes using lasers. However, this method has not yet been tested experimentally.

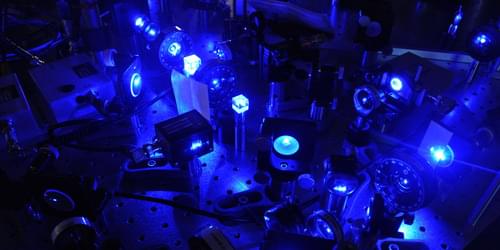

The team of scientists, led by Philip Gibbs, proposed to create Kerr-Newman black holes by colliding two high-energy laser beams. The collision would create a plasma that would be compressed and heated to extreme temperatures, creating a black hole.

Abstract

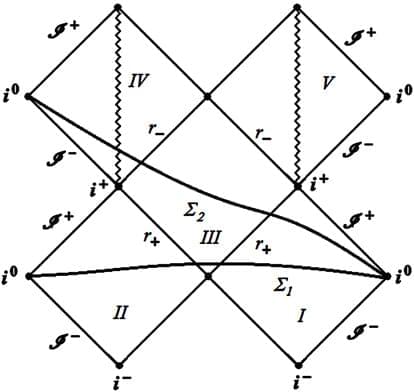

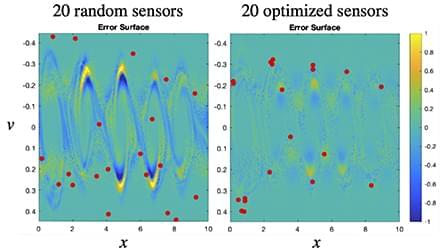

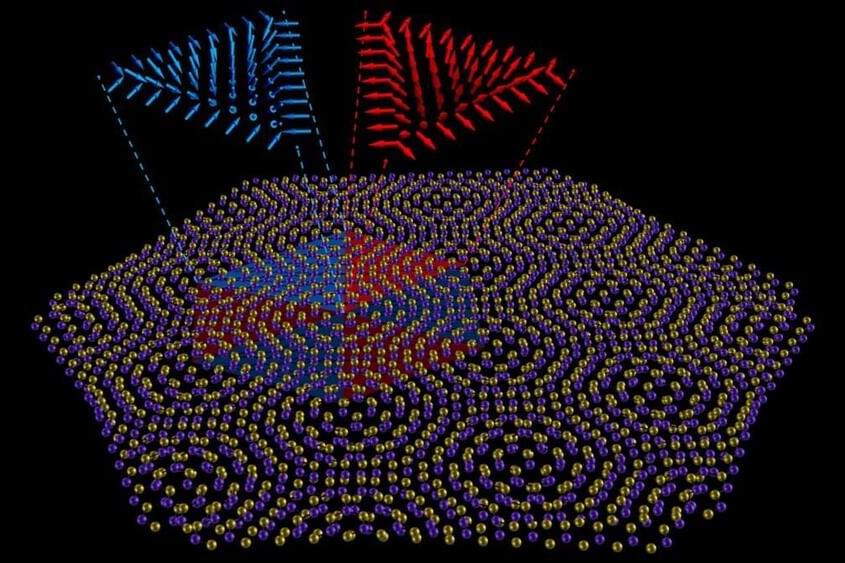

Note, that micro black holes last within micro seconds, and that we wish to ascertain how to build, in a laboratory, a black hole, which may exist say at least up to 10^−1 seconds and provide a test bed as to early universe gravitational theories. First of all, it would be to determine, if the mini black hole bomb, would spontaneously occur, unless the Kerr-Newmann black hole were carefully engineered in the laboratory. Specifically, we state that this paper is modeling the creation of an actual Kerr Newman black hole via laser physics, or possibly by other means. We initiate a model of an induced Kerr-Newman black Holes, with specific angular momentum J, and then from there model was to what would happen as to an effective charge, Q, creating an E and B field, commensurate with the release of GWs. The idea is that using a frame of reference trick, plus E + i B = −function of the derivative of a complex valued scalar field, as given by Appell, in 1887, and reviewed by Whittaker and Watson, 1927 of their “A Course of Modern Analysis” tome that a first principle identification of a B field, commensurate with increase of thermal temperature, T, so as to have artificially induced GW production. This is compared in part with the Park 1955 paper of a spinning rod, producing GW, with the proviso that both the spinning rod paper, and this artificial Kerr-Newman Black hole will employ the idea of lasers in implementation of their respective GW radiation. The idea is in part partly similar to an idea the author discussed with Dr. Robert Baker, in 2016 with the difference that a B field would be generated and linked to effects linked with induced spin to the Kerr-Newman Black hole. We close with some observations about the “black holes have no hair” theorem, and our problem. Citing some recent suppositions that this “theorem” may not be completely true and how that may relate to our experimental situation. We close with observations from Haijicek, 2008 as which may be pertinent to Quantization of Gravity. Furthermore as an answer to questions raised by a referee, we will have a final statement as to how this problem is for a real black hole being induced, and answering his questions in his review, which will be included in a final appendix to this paper. The main issue which is now to avoid the black hole bomb effect which would entail an explosion of a small black hole in a laboratory. Furthermore as an answer to questions raised by a referee, we will have a final statement as to how this problem is for a real black hole being induced, and answering his questions in his review, which will be included in a final appendix to this paper. In all, the main end result is to try to avoid the so called black hole bomb effect, where a mini black hole would explode in a laboratory setting within say 10^−16 or so seconds, i.e. the idea would be to have a reasonably stable configuration within put laser energy, but a small mass, and to do it over hopefully 1015 or more times longer than the 10^−16 seconds where the mini black hole would quickly evaporate. I.e. a duration of say up to 10^−1 seconds which would provide a base line as to astrophysical modeling of a Kerr-Newman black hole.

Kerr Newman Black Hole, High-Frequency Gravitational Waves (HGW), Causal Discontinuity