Physicists have created a visible, self-sustaining “time crystal” using swirling liquid crystals that move in endlessly repeating patterns when illuminated. Imagine a clock that runs forever without batteries or wiring, its hands turning on their own without stopping. In a recent study, physic

Category: physics – Page 17

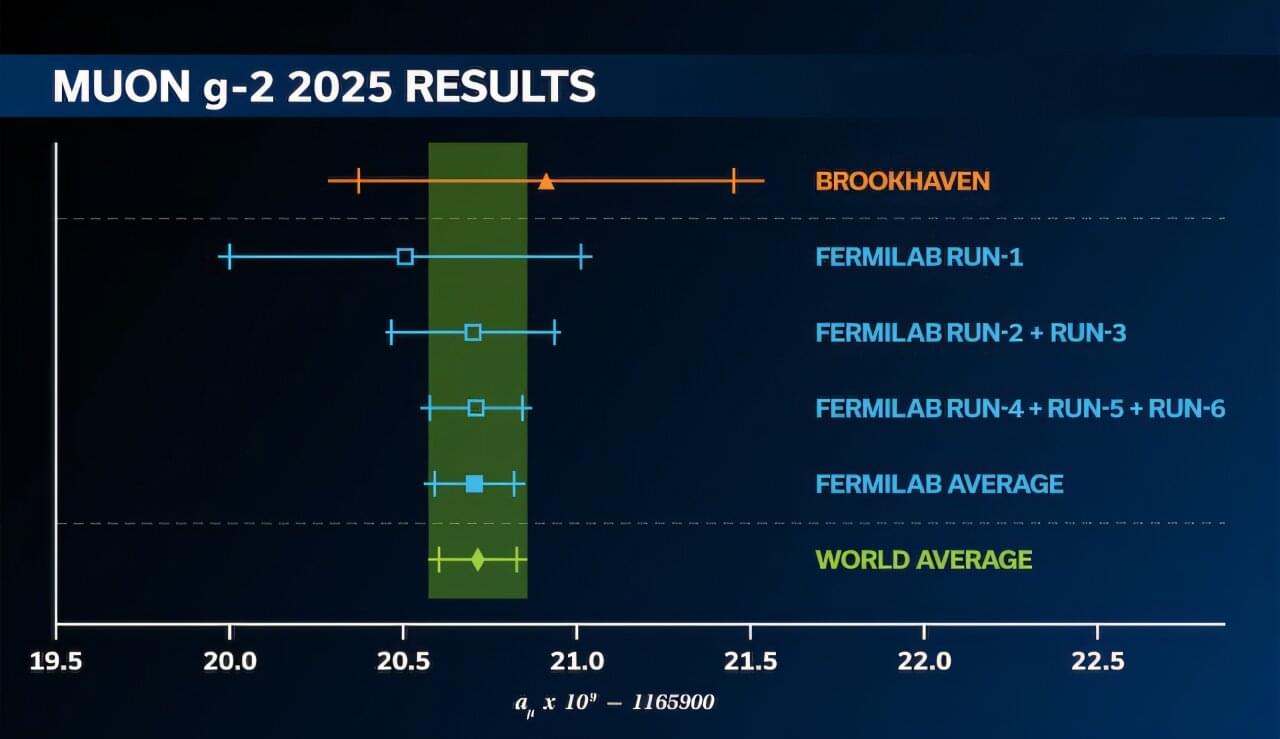

Final experimental result for the muon still challenges theorists

For experimental physicists, the latest measurement of the muon is the best of times. For theorists there’s still work to do.

Colliding 300 billion muons over four years at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in the U.S., the Muon g-2 Collaboration —a group of over 200 researchers—has measured the magnetic strength of the muon to unprecedented precision: accurate to 127 parts per billion.

These final results on the muon’s magnetic moment—measured by its frequency of the moment’s wobbling in an external magnetic field—are the end of a chain of experimental efforts going back 30 years and have been published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

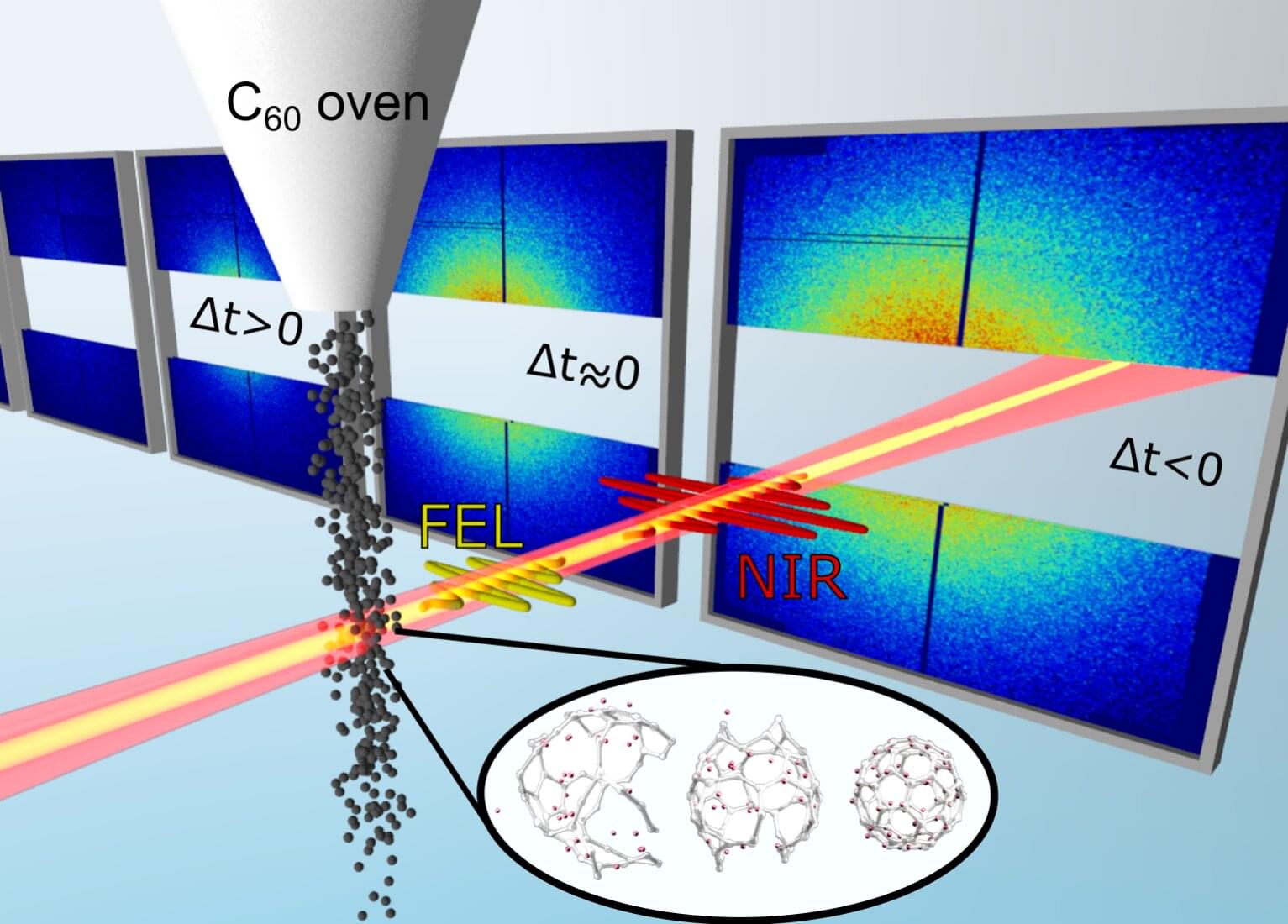

Laser-induced break-up of C₆₀ fullerenes caught in real-time on X-ray camera

The understanding of complex many-body dynamics in laser-driven polyatomic molecules is crucial for any attempt to steer chemical reactions by means of intense light fields. Ultrashort and intense X-ray pulses from accelerator-based free electron lasers (FELs) now open the door to directly watch the strong reshaping of molecules by laser fields.

A prototype molecule, the famous football-shaped “Buckminsterfullerene” C₆₀, was studied both experimentally and theoretically by physicists from two Max Planck Institutes, the one for Nuclear Physics (MPIK) in Heidelberg and the one for the Physics of Complex Systems (MPI-PKS) in Dresden in collaboration with groups from the Max Born Institute (MBI) in Berlin and other institutions from Switzerland, U.S. and Japan.

For the first time, the experiment carried out at the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) of the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory could image strong-laser-driven molecular dynamics in C₆₀ directly.

Are The Fundamental Constants Finely Tuned? | The Naturalness Problem

Learn More About Anydesk: https://anydesk.com/spacetime.

Did God have any choice in creating the world? So asked Albert Einstein. He was being poetic. What he really meant, was whether the universe could have been any other way. Could it have had different laws of physics, driven by different fundamental constants. Or is this one vast and complex universe the inevitable result of an inevitable and unique underlying principle, perhaps expressible as a supremely elegant Theory of Everything. It certainly seems that Einstein thought this should be the case … that God had no choice in whether or how to create the world. It seems like a pretty arm-chair philosophical and perhaps unanswerable question, but the modern “problem” of naturalness may lead to an answer.

Check Out Our Patreon Interview with Looking Glass Universe Here:

Sign Up on Patreon to get access to the Space Time Discord!

https://www.patreon.com/pbsspacetime.

Check out the Space Time Merch Store.

https://www.pbsspacetime.com/shop.

Sign up for the mailing list to get episode notifications and hear special announcements!

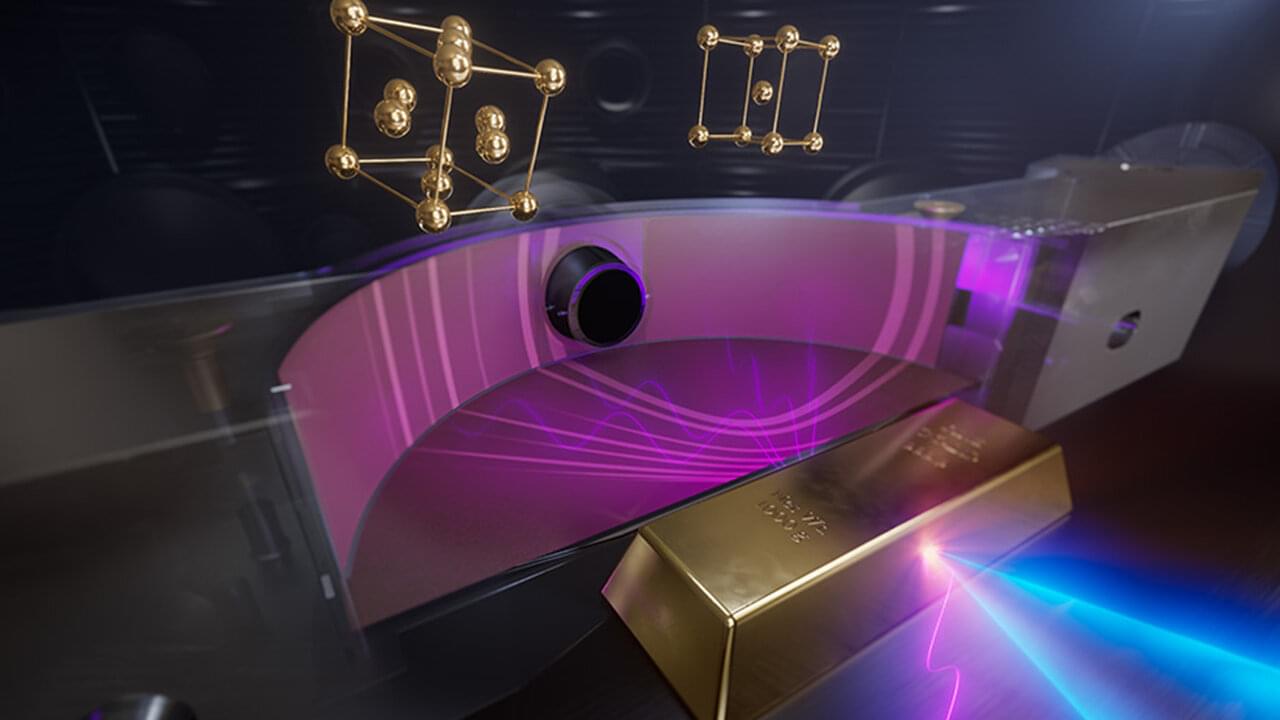

Watching gold’s atomic structure change at 10 million times Earth’s atmospheric pressure

The inside of giant planets can reach pressures more than one million times the Earth’s atmosphere. As a result of that intense pressure, materials can adopt unexpected structures and properties. Understanding matter in this regime requires experiments that push the limits of physics in the laboratory.

In a recent paper published in Physical Review Letters, researchers at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) and their collaborators conducted such experiments with gold, achieving the highest-pressure structural measurement ever made for the material. The results, which show gold switching structure at 10 million times the Earth’s atmospheric pressure, are essential for planetary modeling and fusion science.

“These experiments uncover the atomic rearrangements that occur at some of the most extreme pressures achievable in laboratory experiments,” said LLNL scientist and author Amy Coleman.

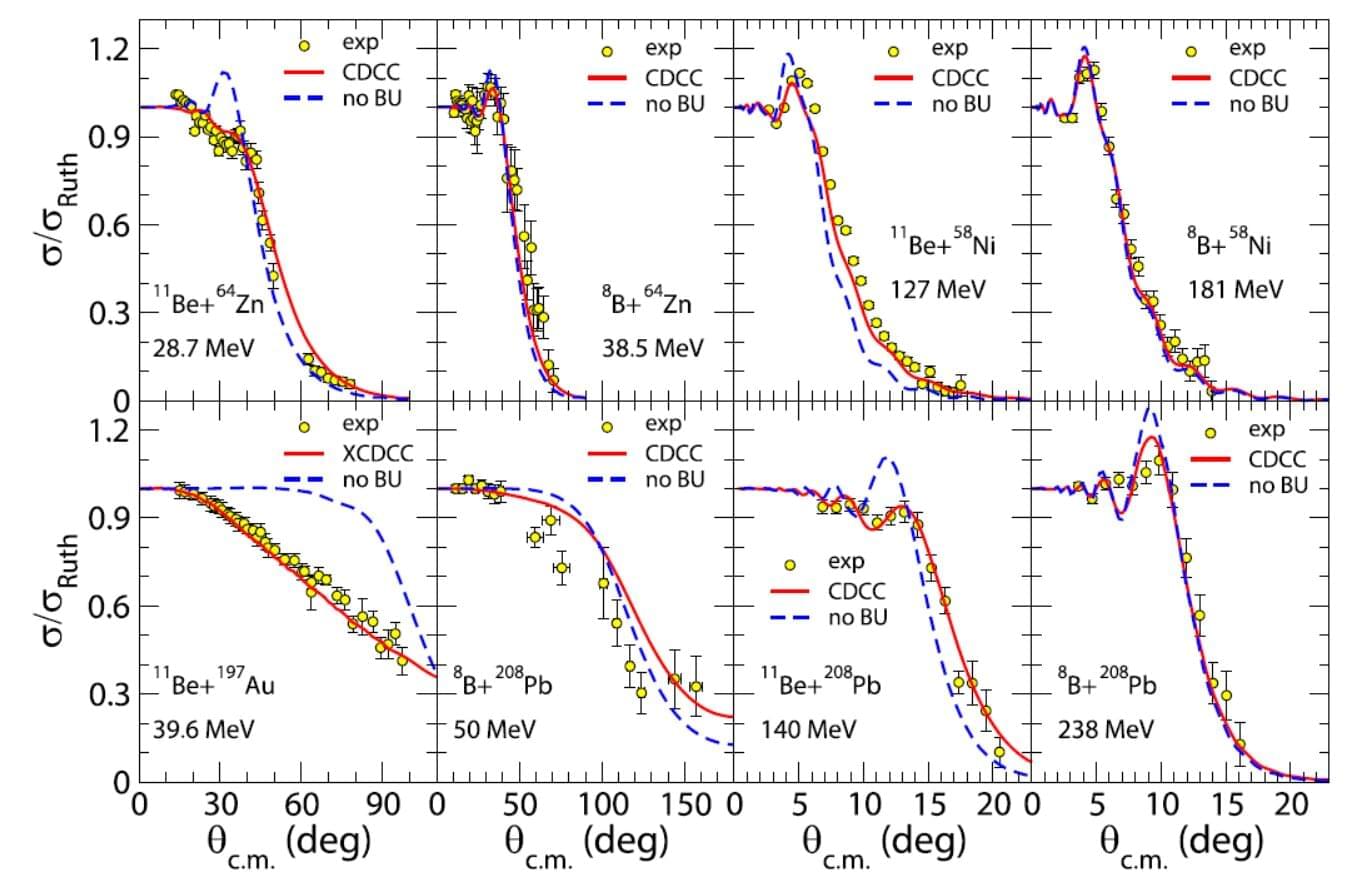

Study sheds new light on reaction dynamics of weakly bound nuclei

Researchers from the Institute of Modern Physics (IMP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have reported new experimental results that advance our understanding of reaction dynamics and exotic nuclear structures of weakly bound nuclei.

The findings are published in Physics Letters B.

Weakly bound nuclei are characterized by their extremely low binding energy of protons and neutrons. Investigating their reaction mechanisms and exotic structures represents a frontier field in nuclear physics.

The Intelligence Foundation Model Could Be The Bridge To Human Level AI

Cai Borui and Zhao Yao from Deakin University (Australia) presented a concept that they believe will bridge the gap between modern chatbots and general-purpose AI. Their proposed “Intelligence Foundation Model” (IFM) shifts the focus of AI training from merely learning surface-level data patterns to mastering the universal mechanisms of intelligence itself. By utilizing a biologically inspired “State Neural Network” architecture and a “Neuron Output Prediction” learning objective, the framework is designed to mimic the collective dynamics of biological brains and internalize how information is processed over time. This approach aims to overcome the reasoning limitations of current Large Language Models, offering a scalable path toward true Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and theoretically laying the groundwork for the future convergence of biological and digital minds.

The Intelligence Foundation Model represents a bold new proposal in the quest to build machines that can truly think. We currently live in an era dominated by Large Language Models like ChatGPT and Gemini. These systems are incredibly impressive feats of engineering that can write poetry, solve coding errors, and summarize history. However, despite their fluency, they often lack the fundamental spark of what we consider true intelligence.

They are brilliant mimics that predict statistical patterns in text but do not actually understand the world or learn from it in real-time. A new research paper suggests that to get to the next level, we need to stop modeling language and start modeling the brain itself.

Borui Cai and Yao Zhao have introduced a concept they believe will bridge the gap between today’s chatbots and Artificial General Intelligence. Published in a preprint on arXiv, their research argues that existing foundation models suffer from severe limitations because they specialize in specific domains like vision or text. While a chatbot can tell you what a bicycle is, it does not understand the physics of riding one in the way a human does.

Explainable AI and turbulence: A fresh look at an unsolved physics problem

While atmospheric turbulence is a familiar culprit of rough flights, the chaotic movement of turbulent flows remains an unsolved problem in physics. To gain insight into the system, a team of researchers used explainable AI to pinpoint the most important regions in a turbulent flow, according to a Nature Communications study led by the University of Michigan and the Universitat Politècnica de València.

A clearer understanding of turbulence could improve forecasting, helping pilots navigate around turbulent areas to avoid passenger injuries or structural damage. It can also help engineers manipulate turbulence, dialing it up to help industrial mixing like water treatment or dialing it down to improve fuel efficiency in vehicles.

“For more than a century, turbulence research has struggled with equations too complex to solve, experiments too difficult to perform, and computers too weak to simulate reality. Artificial Intelligence has now given us a new tool to confront this challenge, leading to a breakthrough with profound practical implications,” said Sergio Hoyas, a professor of aerospace engineering at the Universitat Politècnica de València and co-author of the study.

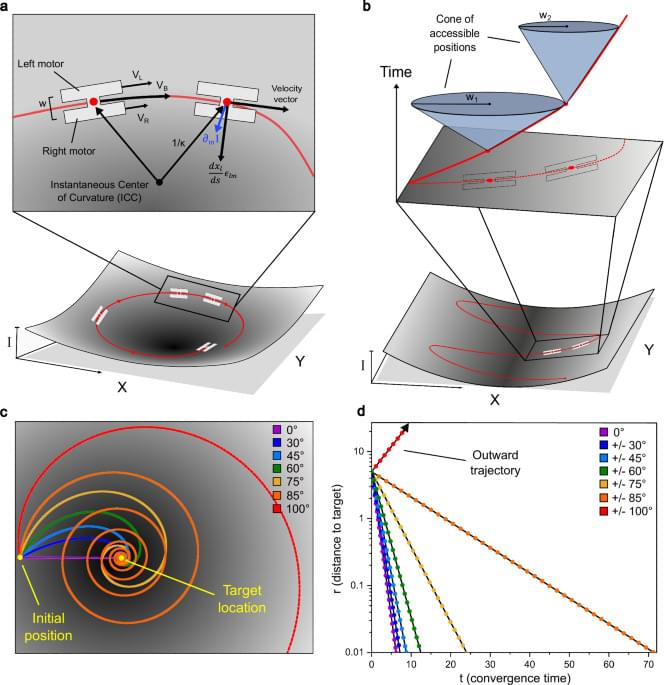

Artificial spacetimes for reactive control of resource-limited robots

Not metaphorically—literally. The light intensity field becomes an artificial “gravity,” and the robot’s trajectory becomes a null geodesic, the same path light takes in warped spacetime.

By calculating the robot’s “energy” and “angular momentum” (just like planetary orbits), they mathematically prove: robots starting within 90 degrees of a target will converge exponentially, every time. No simulations or wishful thinking—it’s a theorem.

They use the Schwarz-Christoffel transformation (a tool from black hole physics) to “unfold” a maze onto a flat rectangle, program a simple path, then “fold” it back. The result: a single, static light pattern that both guides robots and acts as invisible walls they can’t cross.

npj Robot ics — Artificial spacetimes for reactive control of resource-limited robots. npj Robot 3, 39 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44182-025-00058-9

It Took Physicists 50 Years To Prove Einstein Right About This

Increase your problem solving skills with Brilliant! Start learning science and maths for free at https://brilliant.org/sabine/ and get 20% off a premium subscription, which includes daily unlimited access!

Over a century ago, Einstein wrote his theories of special relativity and general relativity. Within those theories, he predicted that, as an object moves faster, it slightly contracts in length. However, 50 years later Penrose and Terrell predicted that what one would see is instead that the object is rotated. In a recent experiment, physicists proved that this Penrose-Terrell effect is actually real. Let’s take a look.

Paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s4200… to what I say: The object (frame) they used is obviously not a cube (as you can see in the photo), it has dimensions of 1 × 1 × 0.6 m. 🤓 Check out my new quiz app ➜ http://quizwithit.com/ 📚 Buy my book ➜ https://amzn.to/3HSAWJW 💌 Support me on Donorbox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg 📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/ 👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine 📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle… 👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl… 🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder #science #sciencenews #physics #relativity.

Correction to what I say: The object (frame) they used is obviously not a cube (as you can see in the photo), it has dimensions of 1 × 1 × 0.6 m.

🤓 Check out my new quiz app ➜ http://quizwithit.com/

📚 Buy my book ➜ https://amzn.to/3HSAWJW

💌 Support me on Donorbox ➜ https://donorbox.org/swtg.

📝 Transcripts and written news on Substack ➜ https://sciencewtg.substack.com/

👉 Transcript with links to references on Patreon ➜ / sabine.

📩 Free weekly science newsletter ➜ https://sabinehossenfelder.com/newsle…

👂 Audio only podcast ➜ https://open.spotify.com/show/0MkNfXl…

🔗 Join this channel to get access to perks ➜

/ @sabinehossenfelder.

#science #sciencenews #physics #relativity