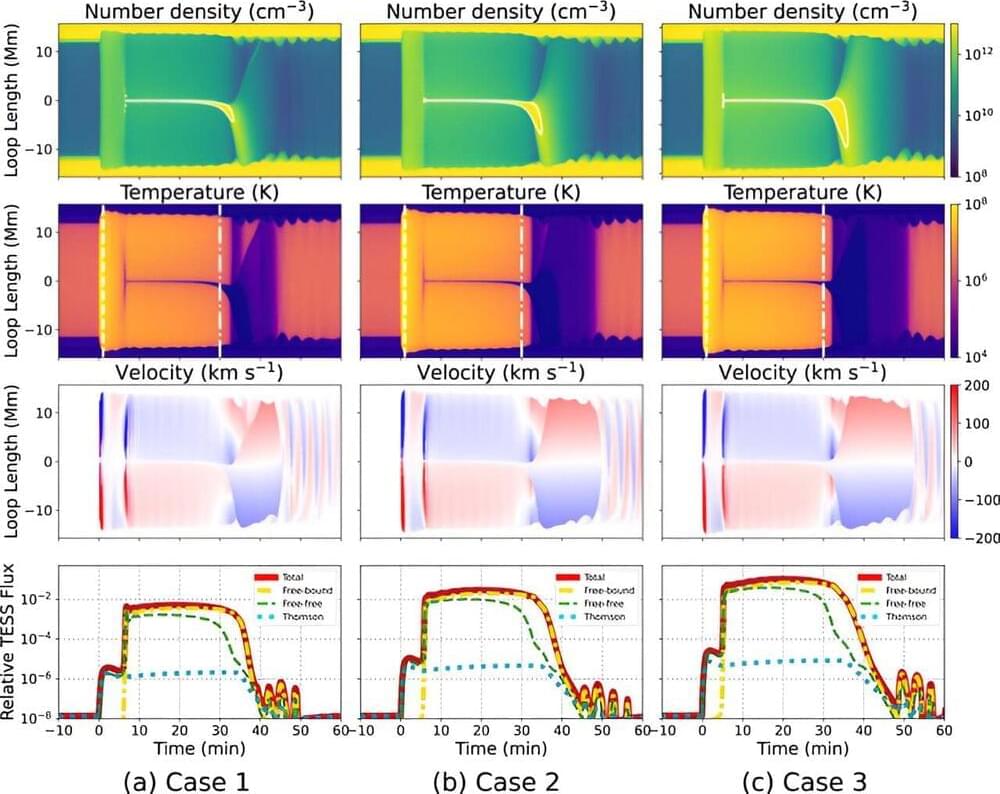

Our sun actively produces solar flares that can impact Earth, with the strongest flares having the capacity to cause blackouts and disrupt communications—potentially on a global scale. While solar flares can be powerful, they are insignificant compared to the thousands of “super flares” observed by NASA’s Kepler and TESS missions. “Super flares” are produced by stars that are 100–10,000 times brighter than those on the sun.

The physics are thought to be the same between solar flares and super flares: a sudden release of magnetic energy. Super-flaring stars have stronger magnetic fields and thus brighter flares but some show an unusual behavior—an initial, short-lived brightness enhancement, followed by a secondary, longer-duration but less intense flare.