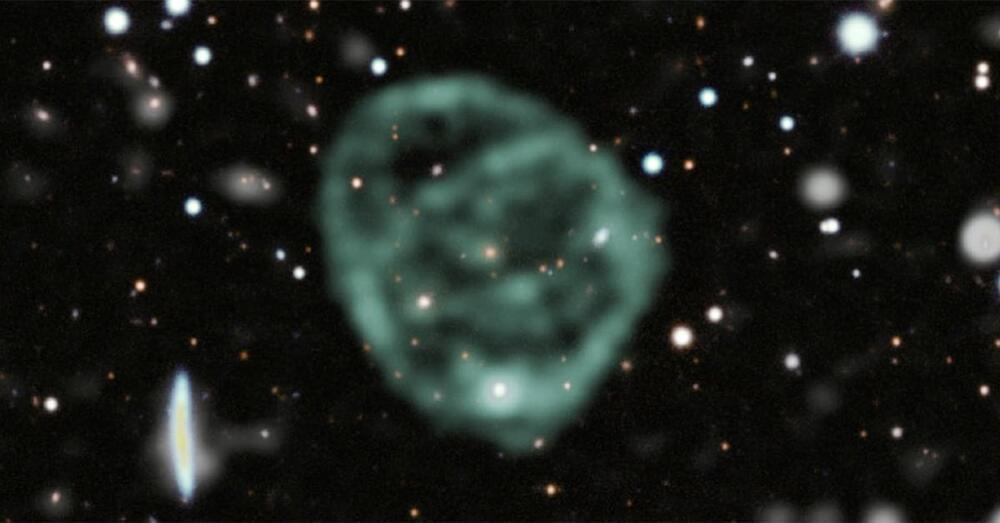

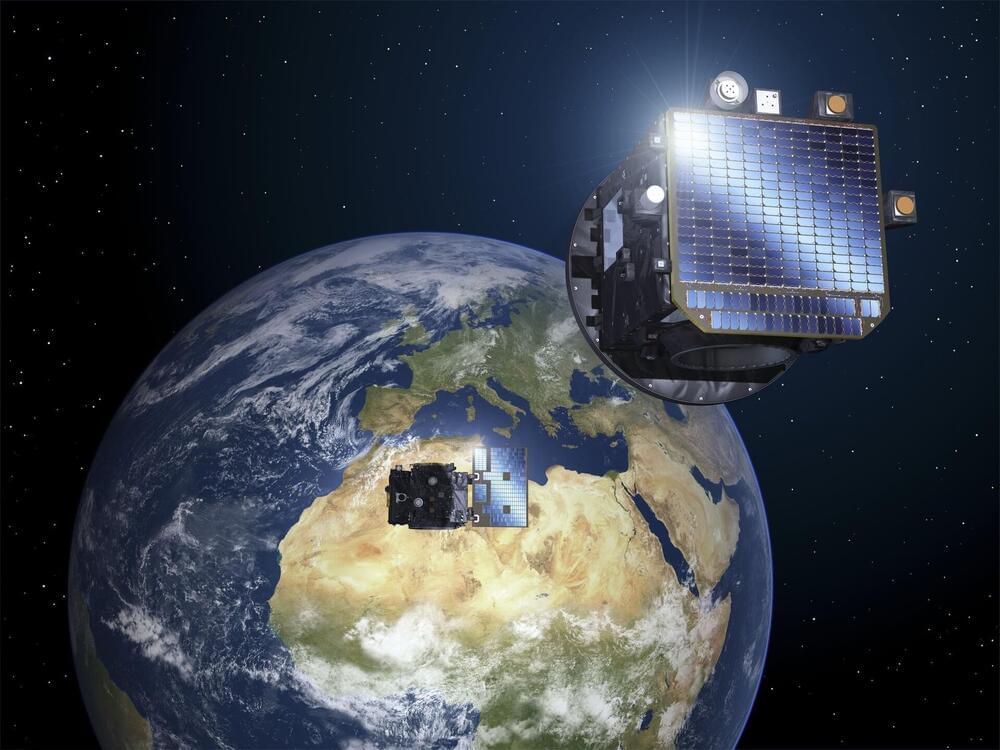

It’s not every day astronomers say, “What is that?” After all, most observed astronomical phenomena are known: stars, planets, black holes and galaxies. But in 2019 the newly completed ASKAP (Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder) telescope picked up something no one had ever seen before: radio wave circles so large they contained entire galaxies in their centers.

As the astrophysics community tried to determine what these circles were, they also wanted to know why the circles were. Now a team led by University of California San Diego Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics Alison Coil believes they may have found the answer: the circles are shells formed by outflowing galactic winds, possibly from massive exploding stars known as supernovae. Their work is published in Nature.

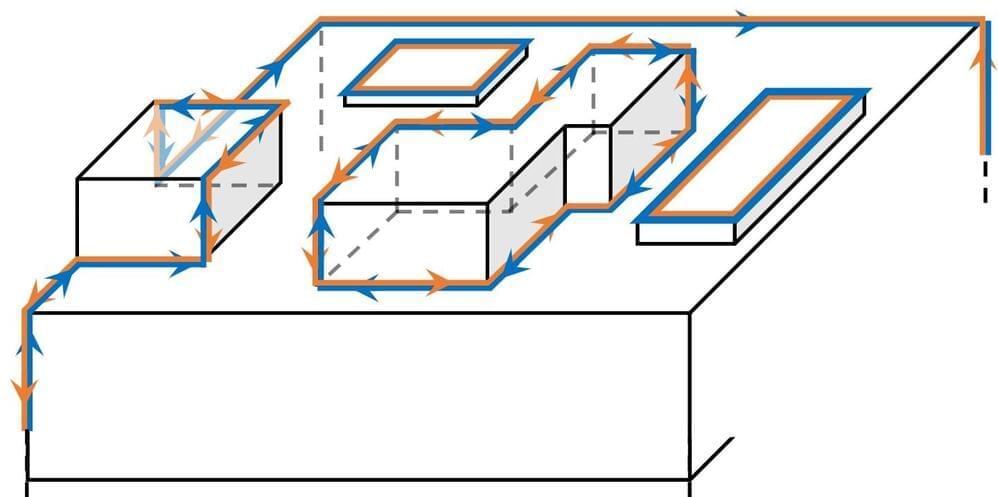

Coil and her collaborators have been studying massive “starburst” galaxies that can drive these ultra-fast outflowing winds. Starburst galaxies have an exceptionally high rate of star formation. When stars die and explode, they expel gas from the star and its surroundings back into interstellar space. If enough stars explode near each other at the same time, the force of these explosions can push the gas out of the galaxy itself into outflowing winds, which can travel at up to 2,000 kilometers/second.