Medical science has changed humanity. It changed what it means to be human, what it means to live a human life. So many of us reading this (and at least one person writing it) owe their lives to medical advances, without which we would have died.

Live expectancy is now well over double what it was for the Medieval Briton, and knocking hard on triple’s door.

What for the future? Extreme life extension is no more inherently ridiculous than human flight or the ability to speak to a person on the other side of the world. Science isn’t magic – and ageing has proven to be a very knotty problem – but science has overcome knotty problems before.

A genuine way to eliminate or severely curtail the influence of ageing on the human body is not in any sense inherently ridiculous. It is, in practice, extremely difficult, but difficult has a tendency to fall before the march of progress. So let us consider what implications a true and seismic advance in this area would have on the nature of human life.

One absolutely critical issue that would surround a breakthrough in this area is the cost. Not so much the cost of research, but the cost of application. Once discovered, is it expensive to do this, or is it cheap? Do you just have to do it once? Is it a cure, or a treatment?

If it can be produced cheaply, and if you only need to do it once, then you could foresee a future where humanity itself moves beyond the ageing process.

The first and most obvious problem that would arise from this is overpopulation. A woman has about 30–35 years of life where she is fertile, and can have children. What if that were extended to 70–100 years? 200 years?

Birth control would take on a vastly more important role than it does today. But then, we’re not just dropping this new discovery into a utopian, liberal future. We’re dropping it into the real world, and in the real world there are numerous places where birth control is culturally condemned. I was born in Ireland, a Catholic nation, where families of 10 siblings or more are not in any sense uncommon.

What of Catholic nations – including some staunchly conservative, and extremely large Catholic societies in Latin America – where birth control is seen as a sin?

Of course, the conservatism of these nations might (might) solve this problem before it arises – the idea of a semi-permanent extension of life might be credibly seen as a deeper and more blasphemous defiance of God than wearing a condom.

But here in the West, the idea that we are allowed to choose how many children we have is a liberty so fundamental that many would baulk to question it.

We may have to.

There is another issue. What about the environmental impact? We’re already having a massive impact on the environment, and it’s not looking pretty. What if there were 10 times more of us? 100 times more? What about the energy consumption needs, in a world running out of petrol? The food needs? The living space? The household waste?

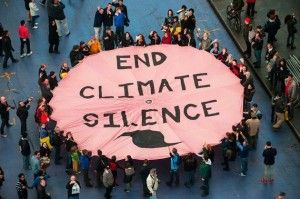

There are already vast flotillas of plastic waste the size of small nations that float across the surface of the Pacific. Carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere have just topped 400 parts per million. We are pushing hard at the envelope of what the world of capable of sustaining, and a massive boost in population would only add to that ever-increasing pressure.

Of course, science might well sort out the answer to those things – but will it sort it out in time? The urgency of environmental science, and cultural change, suddenly takes on a whole new level of importance in the light of a seismic advance in addressing the problem of human ageing.

These are problems that would arise if the advance produced a cheap treatment that could (and would) be consumed by very large numbers of people.

But what if it wasn’t a cure? What if it wasn’t cheap? What if it was a treatment, and a very expensive one?

All of a sudden, we’re looking at a very different set of problems, and the biggest of all centres around something Charlie Chaplin said in the speech he gave at the end of his film, The Great Dictator. It is a speech from the heart, and a speech for the ages, given on the eve of mankind’s greatest cataclysm to date, World War 2.

In fact, you’d be doing yourself a favour if you watched the whole thing, it is an astounding speech.

The quote is this:

“To those who can hear me, I say — do not despair.

The misery that is now upon us is but the passing of greed, the bitterness of men who fear the way of human progress. The hate of men will pass, and dictators die, and the power they took from the people will return to the people. And so long as men die, liberty will never perish.”

And so long as men die, liberty will never perish.

What if Stalin were immortal? And not just immortal, but immortally young?

Immortally vigourous, able to amplify the power of his cult of personality with his literal immortality.

This to me seems a threat of a very different kind, but of no less importance, than the dangers of overpopulation. That so long as men die, liberty will never perish. But what if men no longer die?

And of course, you could very easily say that those of us lucky enough to live in reasonably well-functioning democracies wouldn’t have to worry too much about this. It doesn’t matter if you live to be 1000, you’re still not getting more than 8 years of them in the White House.

But there is something in the West that would be radically changed in nature. Commercial empires.

What if Rupert Murdoch were immortal?

It doesn’t matter how expensive that treatment for ageing is. If it exists, he’d be able to afford it, and if he were able to buy it, he’d almost certainly do so.

If Fox News was run by an immortal business magnate, with several lifetimes worth of business experience and skill to know how to hold it all together, keep it going, keep it growing? What then?

Not perhaps the sunny utopia of a playground of immortals that we might hope for.

This is a different kind of issue. It’s not an external issue – the external impact of population on the environment, or the external need of a growing population to be fed. These problems might well sink us, but science has shown itself extremely adept at finding solutions to external problems.

What this is, is an internal problem. A problem of humanity. More specifically, the fact that extreme longevity would allow tyranny to achieve a level of entrenchment that it has so far never been capable of.

But then a law might be passed. Something similar to the USA’s 8 year term limit on Presidents. You can’t be a CEO for longer than 30 years, or 40 years, or 50. Something like that might help, might even become urgently necessary over time. Forced retirement for the eternally young.

Not an unproblematic idea, I’m sure you’ll agree. Quite the culture shock for Western societies loathe to accept government intervention in private affairs.

But it is a new category of problem. A classic problem of humanity, amplified by immortality. The centralisation of control, power and influence in a world where the people it centres upon cannot naturally die.

This, I would say, is the most obvious knotty problem that would arise, for humanity, in the event of an expensive, but effective, treatment for ageing.

But then, let’s just take a quick look back at the other side of the coin. Is there a problem inherent in humanity that would be amplified were ageing to be overcome, cheaply, worldwide?

Let me ask you a question.

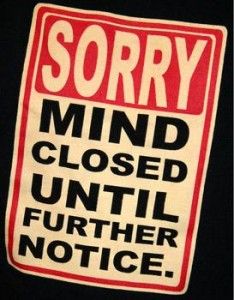

Do people, generally speaking, become more open to new things, or less open to new things, as they age?

Do older people – just in general terms – embrace change or embrace stasis?

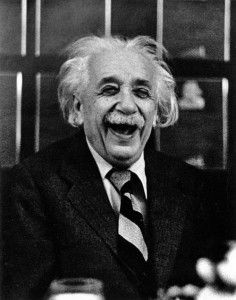

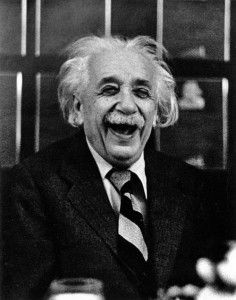

Well, it’s very obvious that some older people do remain young at heart. They remain passionate, humble in their beliefs, they are open to new things, and even embrace them. Some throw the influence and resources they have accrued throughout their lifetimes into this, and are instrumental to the march of progress.

More than this, they add a lifetime of skill, experience and finesse to their passion, a melding of realism and hope that is one of the most precious and potent cocktails that humanity is capable of mixing.

But we’re not talking about the few. We’re talking about the many.

Is it fair to say that most older people take this attitude to change? Or is it fairer to say that older people who retain that passion and spark, who not only have retained it, but have spent a lifetime fuelling it into a great blaze of ability and success – is it fair to say that these people are a minority?

I would say yes. They are incredibly precious, but part of that preciousness is the fact that they are not common.

Perhaps one day we will make our bodies forever young. But what of our spirit? What of our creativity?

I’m not talking about age-related illnesses like Parkinson’s, or Alzheimer’s disease. I’m talking about the creativity, passion and fire of youth.

The temptation of the ‘comfort zone’ for all human beings is a palpable one, and one that every person who lives well, who breaks the mold, who changes the future, must personally overcome.

Do the majority of people overcome it? I would argue no. And more than this, I would argue that living inside a static understanding of the world – even working to protect that understanding in the face of naked and extreme challenges from reality itself – is now, and has historically been, through all human history, the norm.

Those who break the mold, brave the approbation of the crowd, and look to the future with wonder and hope, have always been a minority.

Now add in the factor of time. The retreat into the comforting, the static and the known has a very powerful pull on human beings. It is also not a binary process, but an analogue process – it’s not just a case of you do or you don’t. There are degrees of retreat, extremes of intellectual conservatism, just as there are extremes of intellectual curiosity, and progress.

But which extremes are the more common? This matters, because if all people could live to 200 years old or more, what would that mean for a demographic shift in cultural desire away from change and toward stasis?

A worrying thought. And it might seem that in the light of all this, we should not seek to open the Pandora’s box of eternal life, but should instead stand against such progress, because of the dangers it holds.

But, frankly, this is not an option.

The question is not whether or not human beings should seek to conquer death.

The question is whether or not conquering death is possible.

If it is possible, it will be done. If it is not, it will not be.

But the obvious problem of longevity – massive population expansion – is something that is, at least in principle, amenable to other solutions arising from science as it now practiced. Cultural change is often agonising, but it does happen, and scientific progress may indeed solve the issues of food supply and environmental impact. Perhaps not, but perhaps.

At the very least, these sciences take on a massively greater importance to the cohesion of the human future than they already have, and they are already very important indeed.

But there is another, deeper problem of a very different kind. The issue of the human spirit. If, over time, people (on average) become more calcified in their thinking, more conservative, less likely to take risks, or admit to new possibilities that endanger their understanding, then longevity, distributed across the world, can only lead to a culture where stasis is far more valued than change.

Pandora’s box is already open, and its name is science. Whether it is now, or a hundred years from now, if it is possible for human beings to be rendered immortal through science, someone is going to crack it.

We cannot flinch the future. It would be churlish and naive to assume that such a seemingly impossible vision will forever remain impossible. Not after the last century we just had, where technological change ushered in a new era, a new kind of era, where the impossibilities of the past fell like wheat beneath a scythe.

Scientific progress amplifies the horizon of possible scientific progress. And we stand now at a time when what it means to be a human – something which already undergone enormous change – may change further still, and in ways more profound than any of us can imagine.

If it can be done, it will be done. And so the only sane approach is to look with clarity at what we can see of what that might mean.

The external problems are known problems, and we may yet overcome them. Maybe. If there’s a lot of work, and a lot of people take a lot of issues a lot more seriously than they are already doing.

But there is a different kind of issue. An issue extending from human nature itself. Can we overcome, as a people, as a species, our fear, and the things that send us scurrying back from curiosity and hope into the comforting arms of wilful ignorance, and static belief?

This, in my opinion, is the deepest problem of longevity. Who wants to live forever in a world where young bodies are filled with withered souls, beaten and embittered with the frustrations of age, but empowered to set the world in stone to justify them?

But perhaps it was always going to come to this. That at some point technological advancement would bring us to a kind of reckoning. A reckoning between the forces of human fear, and the value of human courage.

To solve the external problems of an eternal humanity, science must do what science has done so well for so long – to delve into the external, to open up new possibilities to feed the world, and balance human presence with the needs of the Earth.

But to solve the internal problems of an eternal humanity, science needs to go somewhere else. The stunning advances in the understanding of the external world must begin to be matched with new ways of charting the deeps of human nature. The path of courage, of open-mindedness, of humility, and a willingness to embrace change and leave behind the comforting arms of old static belief systems – this is not a path that many choose.

But many more must choose it in a world of immortal people, to counterbalance the conservatism of those who fail the test, and retreat, and live forever.

Einstein lived to a ripe old age, and never lost his wonder. Never lost his humility, or his courage to brave the approbation and ridicule of his peers in that task he set himself. To chart the deep simplicities of the real, and know the mind of God. The failure of the human spirit is not written in the stars, and never will be.

We are none of us doomed to fail in matters of courage, curiosity, wonder or hope. But we are none of us guaranteed to succeed.

And as long as courage, hope and the ability to break new ground remain vague, hidden properties that we squeamishly refuse to interrogate, each new generation will have to start from scratch, and make their own choices.

And in a world of eternal humans, if any individual generation fails, the world will be counting that price for a very long time.

It is a common fear that if we begin to make serious headway into issues normally the domain of the spiritual, we will destroy the mystique of them, and therefore their preciousness.

Similar criticisms were, and sometimes still are, laid at the feet of Darwin’s work, and Galileo’s. But the fact is that an astronomer does not look to the sky with less wonder because of their deeper understanding, but more wonder.

Reality is both stunningly elegant, and infinitely beautiful, and in these things it is massively more amazing than the little tales of mystery humans have used to make sense of it since we came down from the trees.

In the face of a new future, where the consequences of human courage and human failure are amplified, the scientific conquest of death must be fused with another line of inquiry. The scientific pioneering of the fundamental dynamics of courage in living, and humility to the truth, over what we want to believe.

It will never be a common path, and no matter how clear it is made, or how wide it is opened, there will always be many who will never walk it.

But the wider it can be made, the clearer it can be made, the more credible it can be made as an option.

And we will need that option. We need it now.

And our need will only grow greater with time.