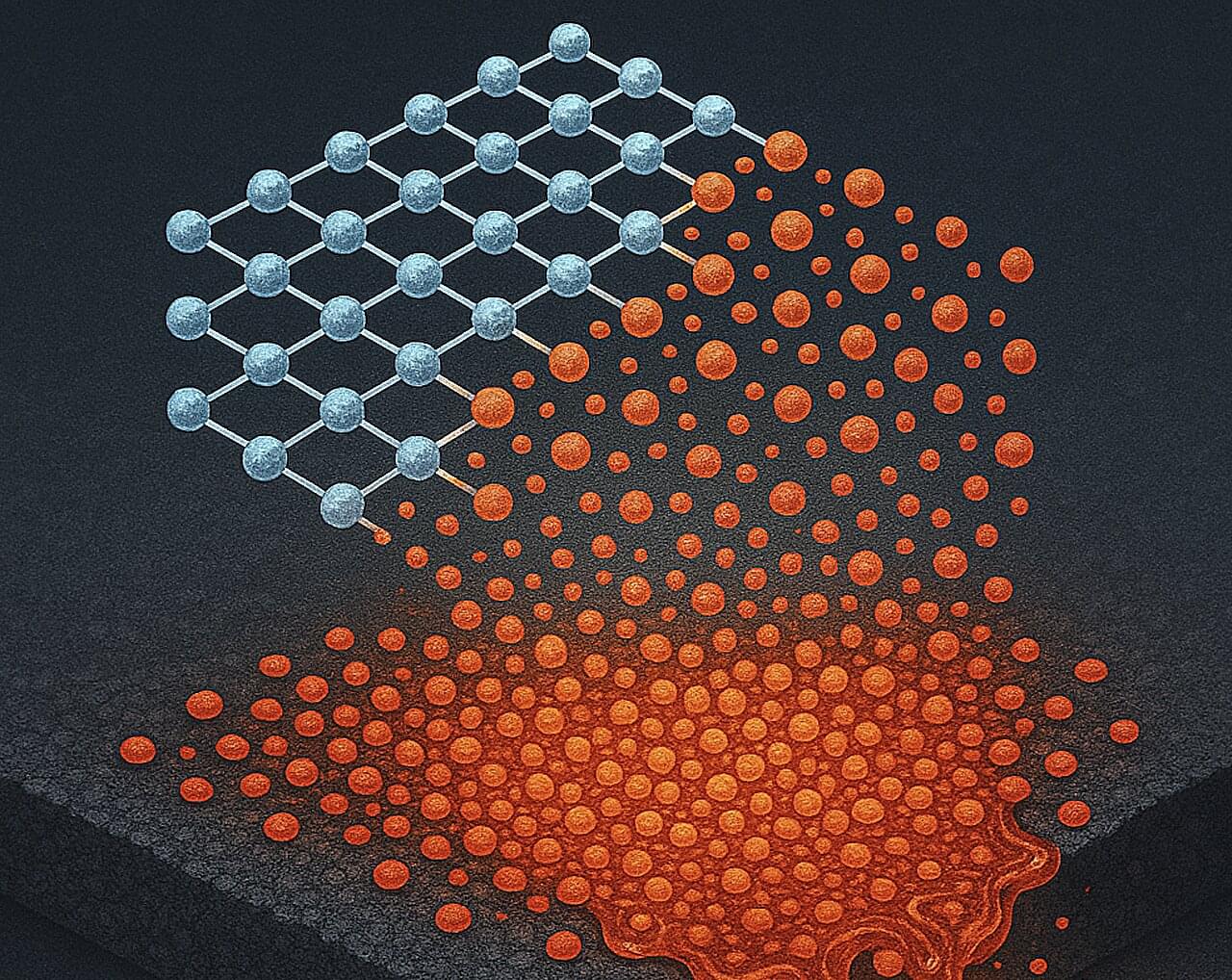

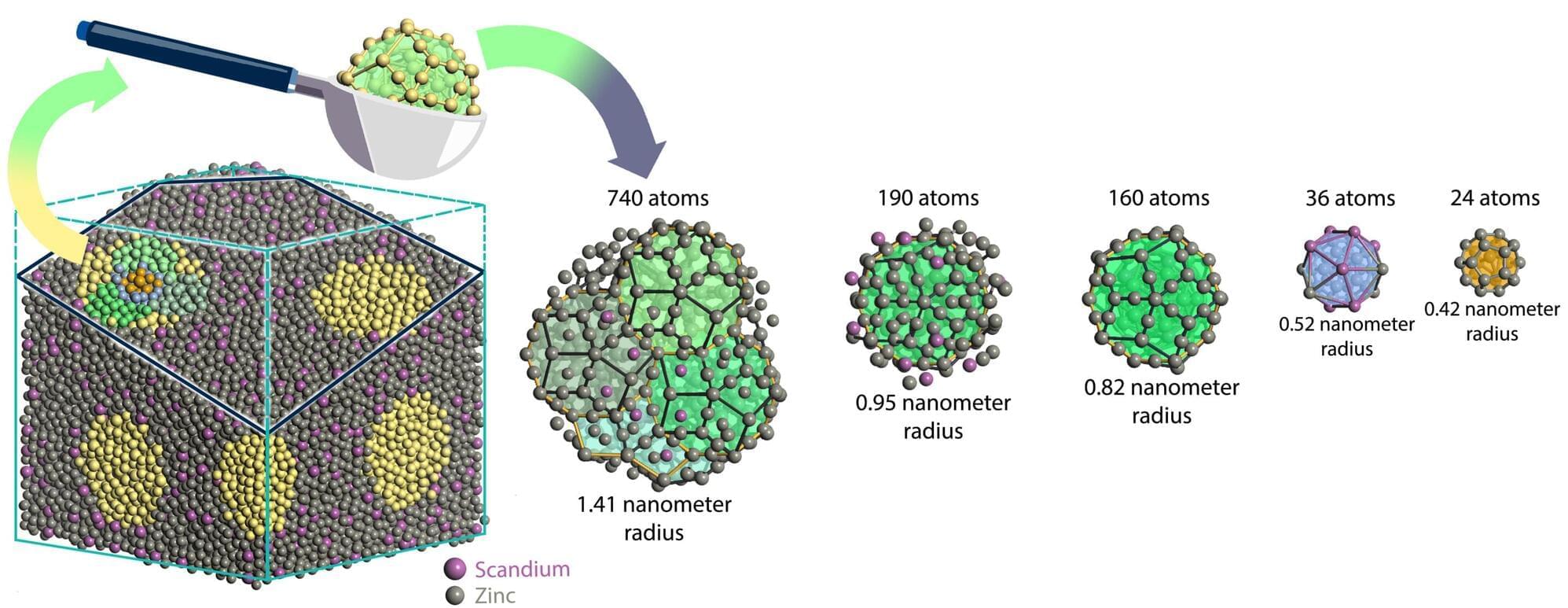

Once considered merely insulating, a change in the angle between silicon and oxygen atoms opens a pathway for electrical charge to flow.

A breakthrough discovery from the University of Michigan has revealed that a new form of silicone can act as a semiconductor. This finding challenges the long-held belief that silicones are only insulating materials.

“The material opens up the opportunity for new types of flat panel displays, flexible photovoltaics, wearable sensors or even clothing that can display different patterns or images,” said Richard Laine, U-M professor of materials science and engineering and macromolecular science and engineering and corresponding author of the study recently published in Macromolecular Rapid Communications.