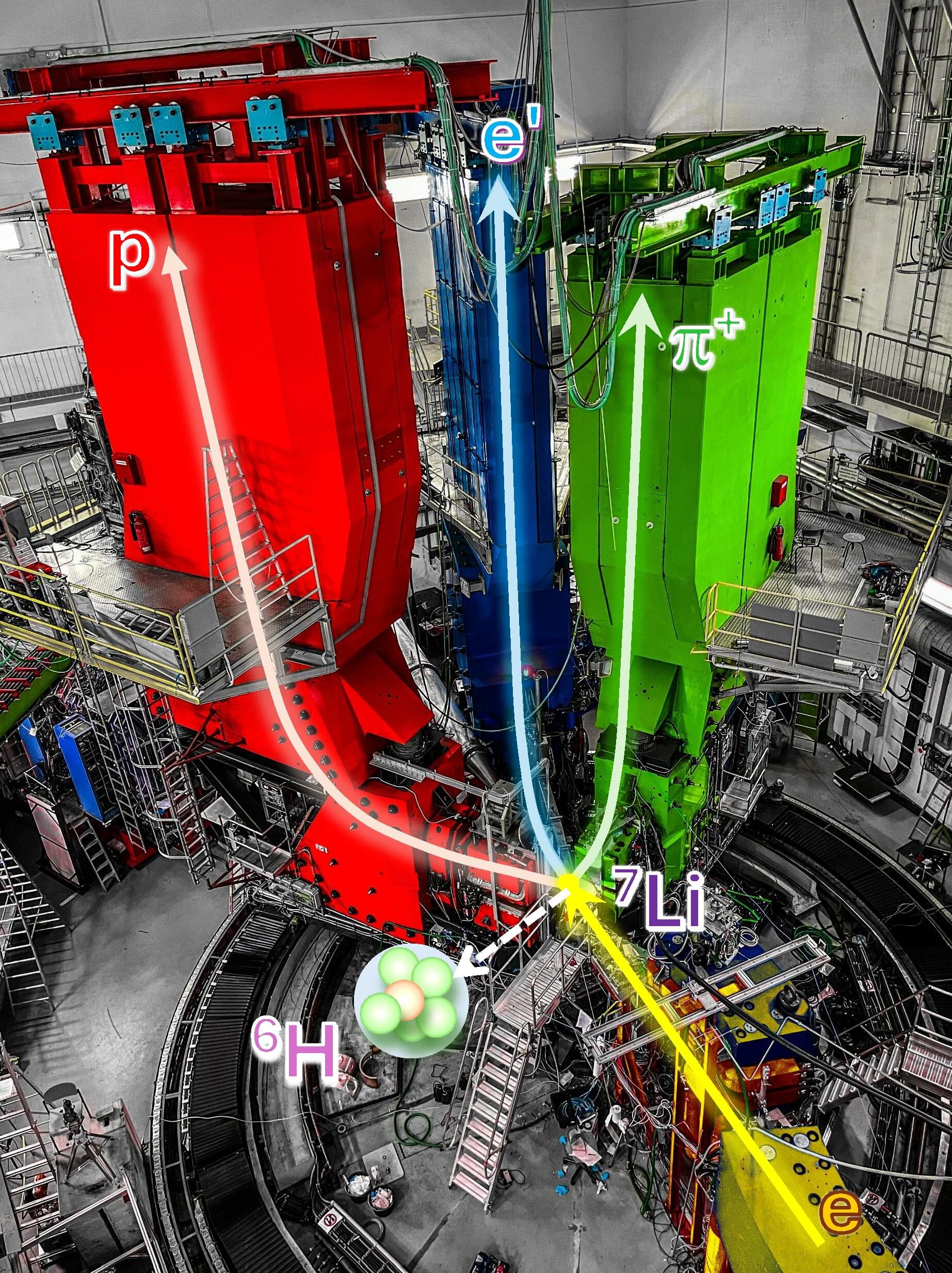

Researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) are tackling one of the most complex challenges in the world of quantum information—how to create reliable, scalable networks that can connect quantum systems over distances.

Their work has resulted in two publications in Physical Review Letters and Science Advances, bringing us one step closer to realizing large-scale networked quantum systems, or even the quantum internet.

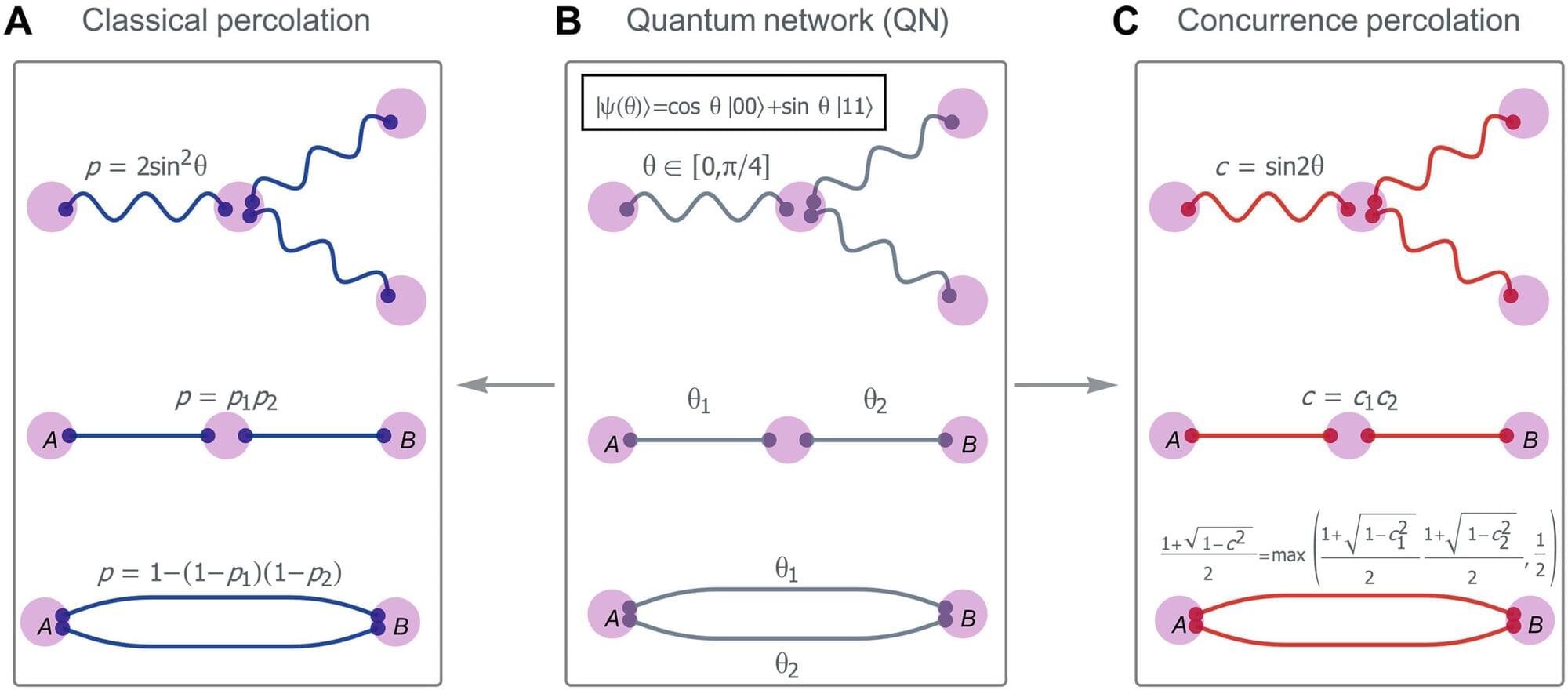

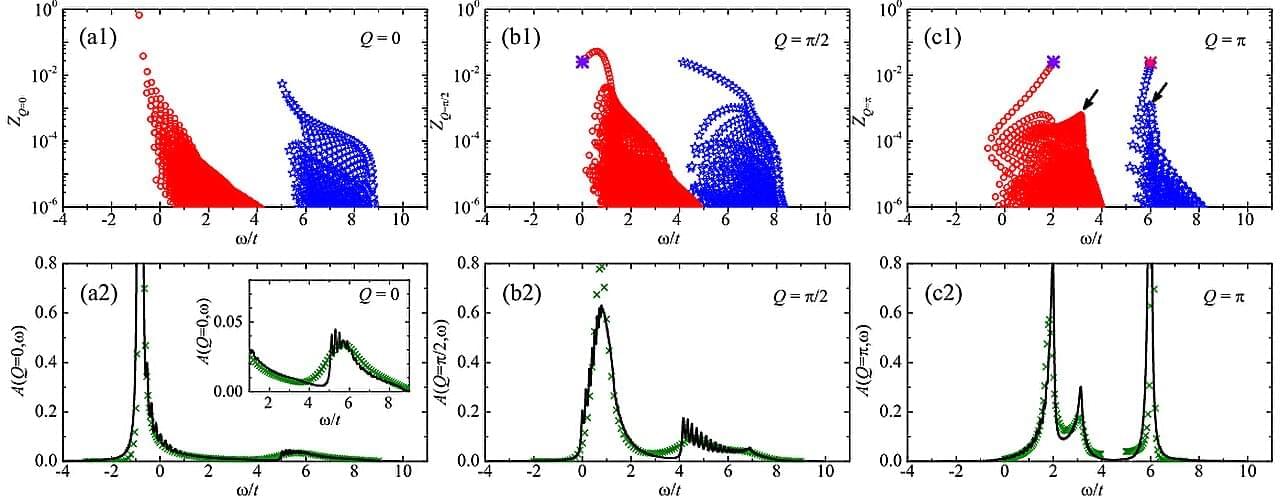

The research team, which includes faculty members from the RPI Department of Physics, Applied Physics, and Astronomy, and the Department of Computer Science, is led by Assistant Professor Xiangyi Meng, Ph.D. Their research focuses on designing quantum networks that use entanglement—a phenomenon where quantum particles become mysteriously correlated.