As searches for the leading dark matter candidates—weakly interacting massive particles, axions, and primordial black holes—continue to deliver null results, the door opens on the exploration of more exotic alternatives. Guanming Liang and Robert Caldwell of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire have now proposed a dark matter candidate that is analogous with a superconducting state [1]. Their proposal involves interacting fermions that could exist in a condensate similar to that formed by Cooper pairs in the Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer theory of superconductivity.

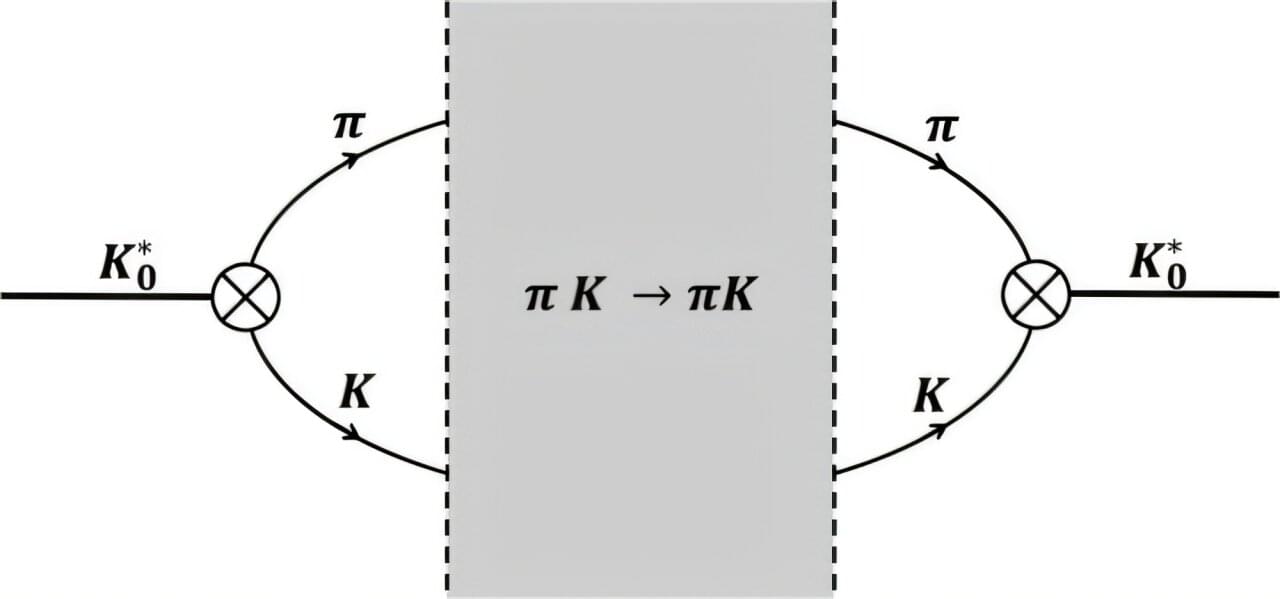

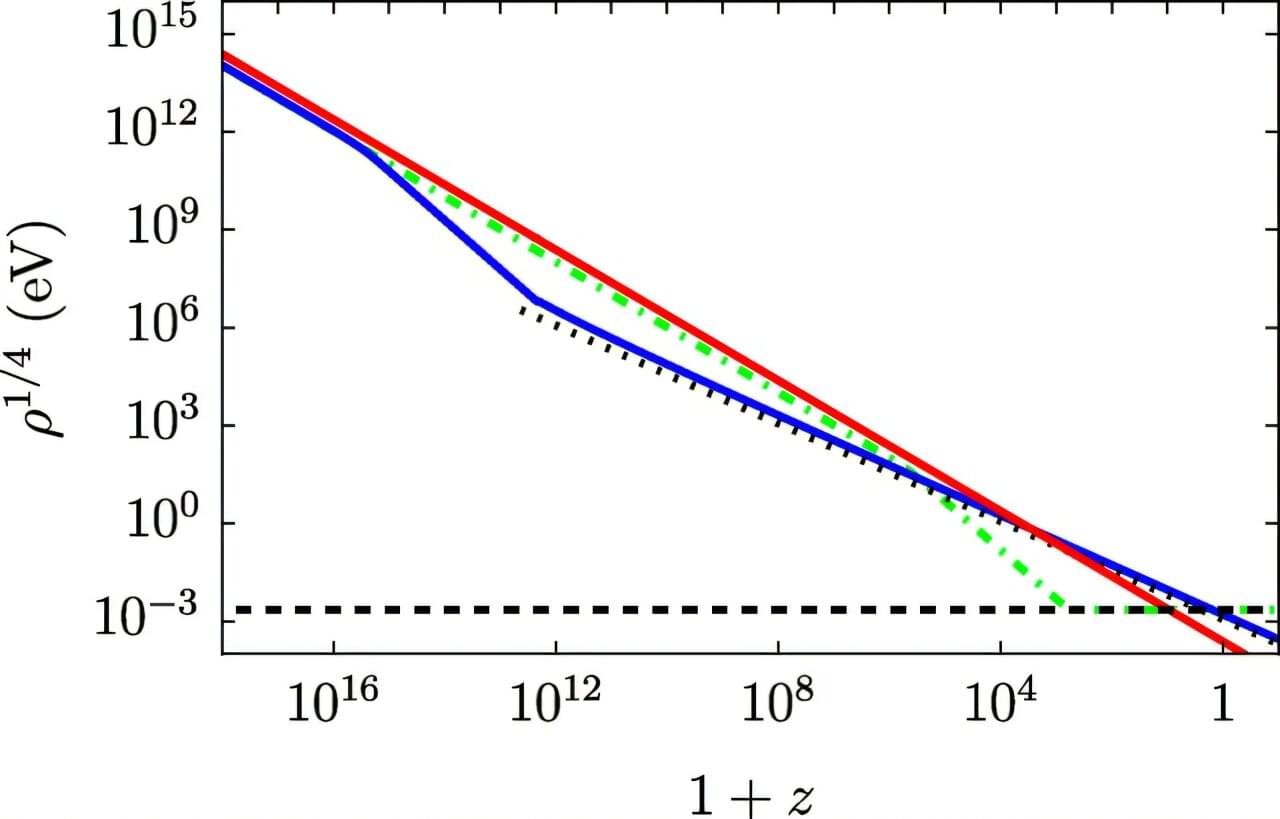

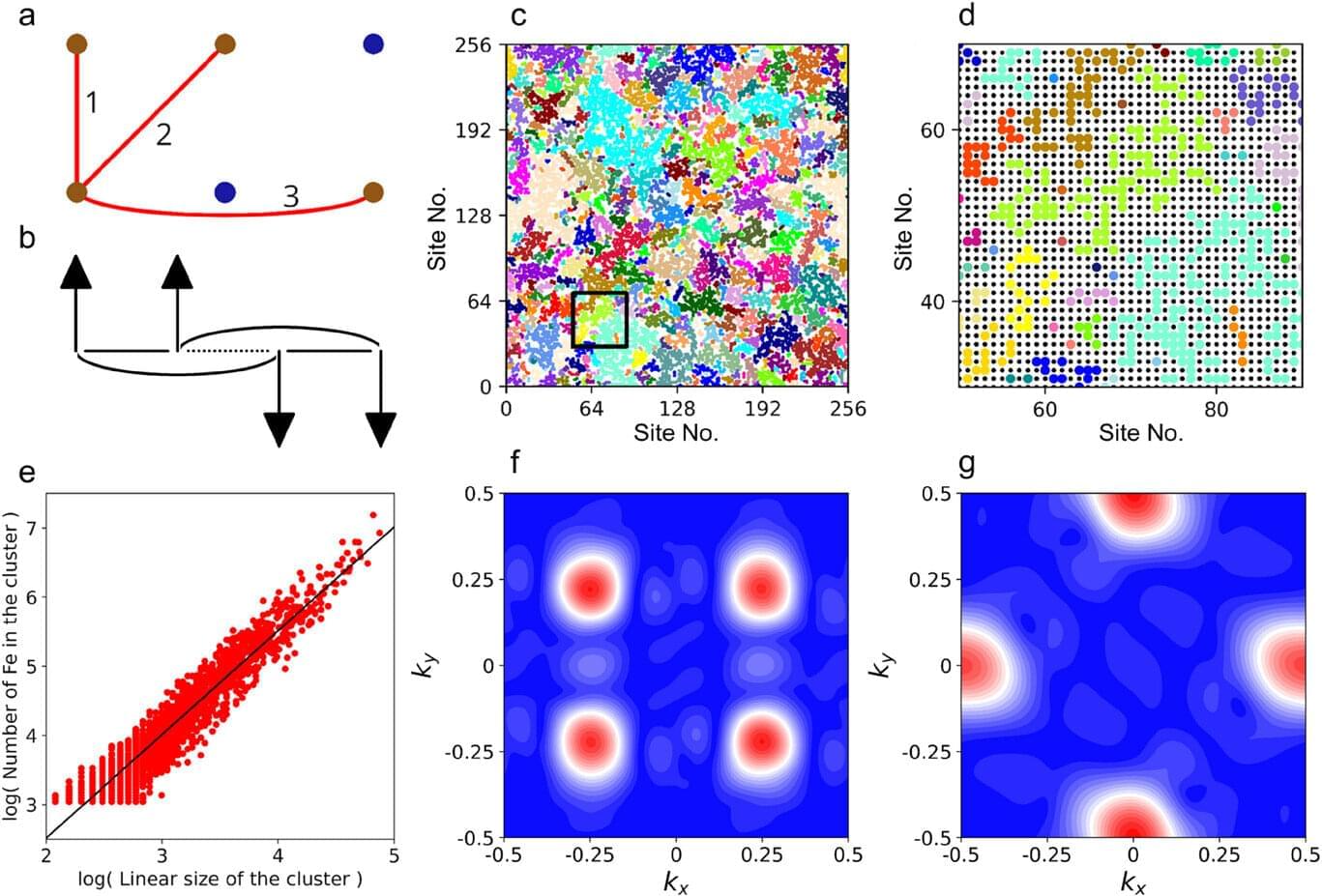

The novel fermions considered by Liang and Caldwell emerge in the Nambu–Jona-Lasinio model, which can be regarded as a low-energy approximation of the quantum chromodynamics theory that describes the strong interaction. The duo considers a scenario where, in the early Universe, the fermions behave like radiation, reaching thermal equilibrium with standard photons. As the Universe expands and the temperature drops below a certain threshold, however, the fermions undergo a phase transition that leads them to pair up and form a massive condensate.

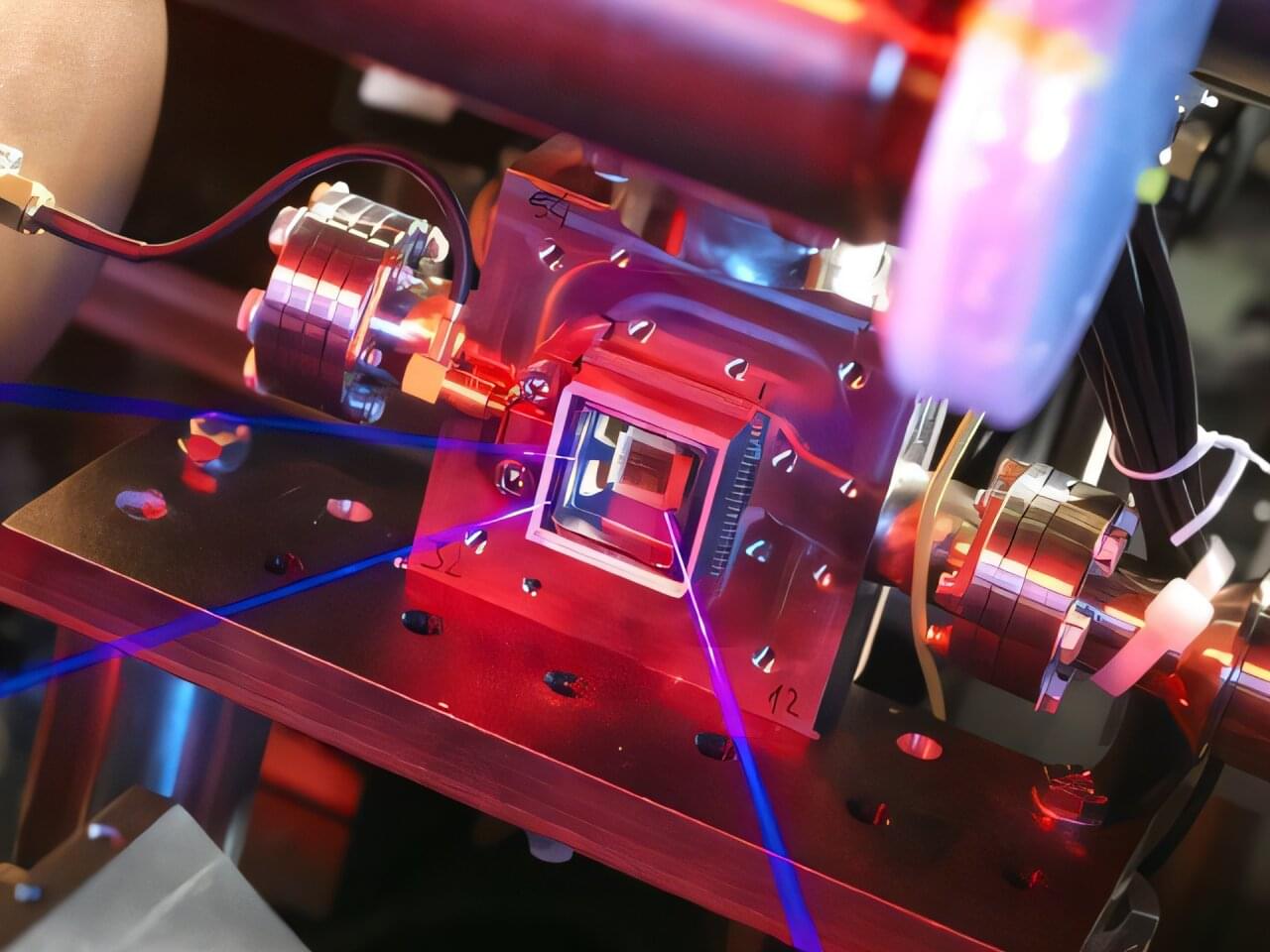

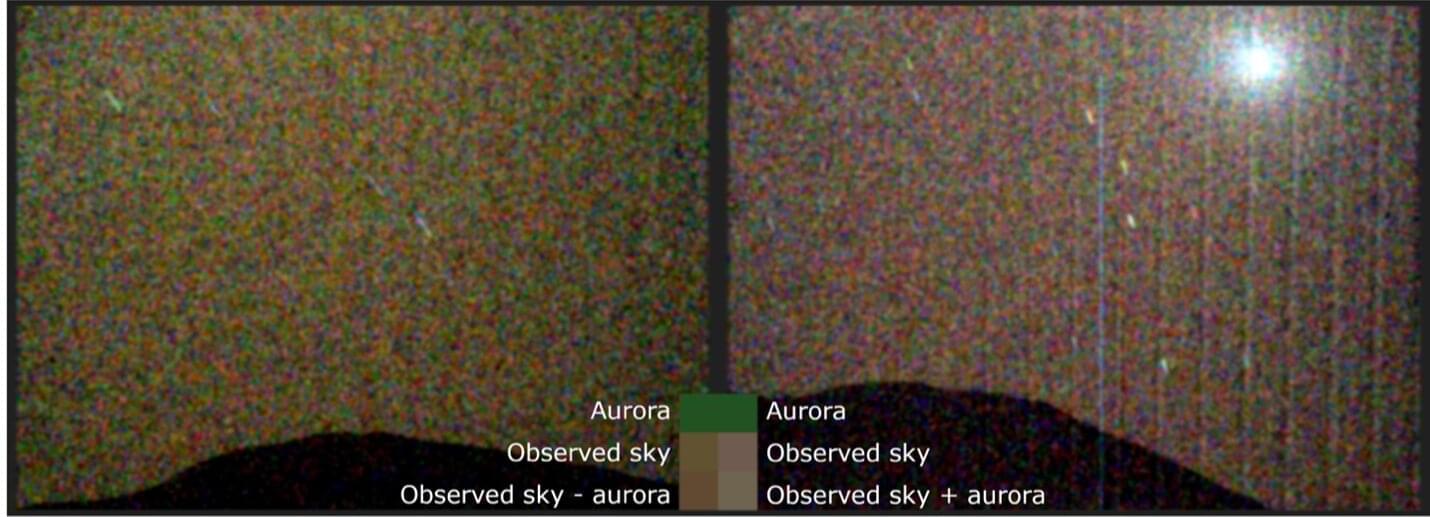

The proposed scenario has several appealing features, say Liang and Caldwell. The fermions’ behavior would be consistent with that of the cold dark matter considered by the current standard model of cosmology. Further, the scenario implies a slight imbalance between fermions with different chiralities (left-and right-handed). Such an imbalance might be related to the yet-to-be-explained matter–antimatter asymmetry seen in the Universe. What’s more, the model predicts that the fermions obey a time-dependent equation of state that would produce unique, potentially observable signatures in the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation. The researchers suggest that next-generation CMB measurements—by the Simons Observatory and by so-called stage 4 CMB telescopes—might reach sufficient precision to vet their idea.