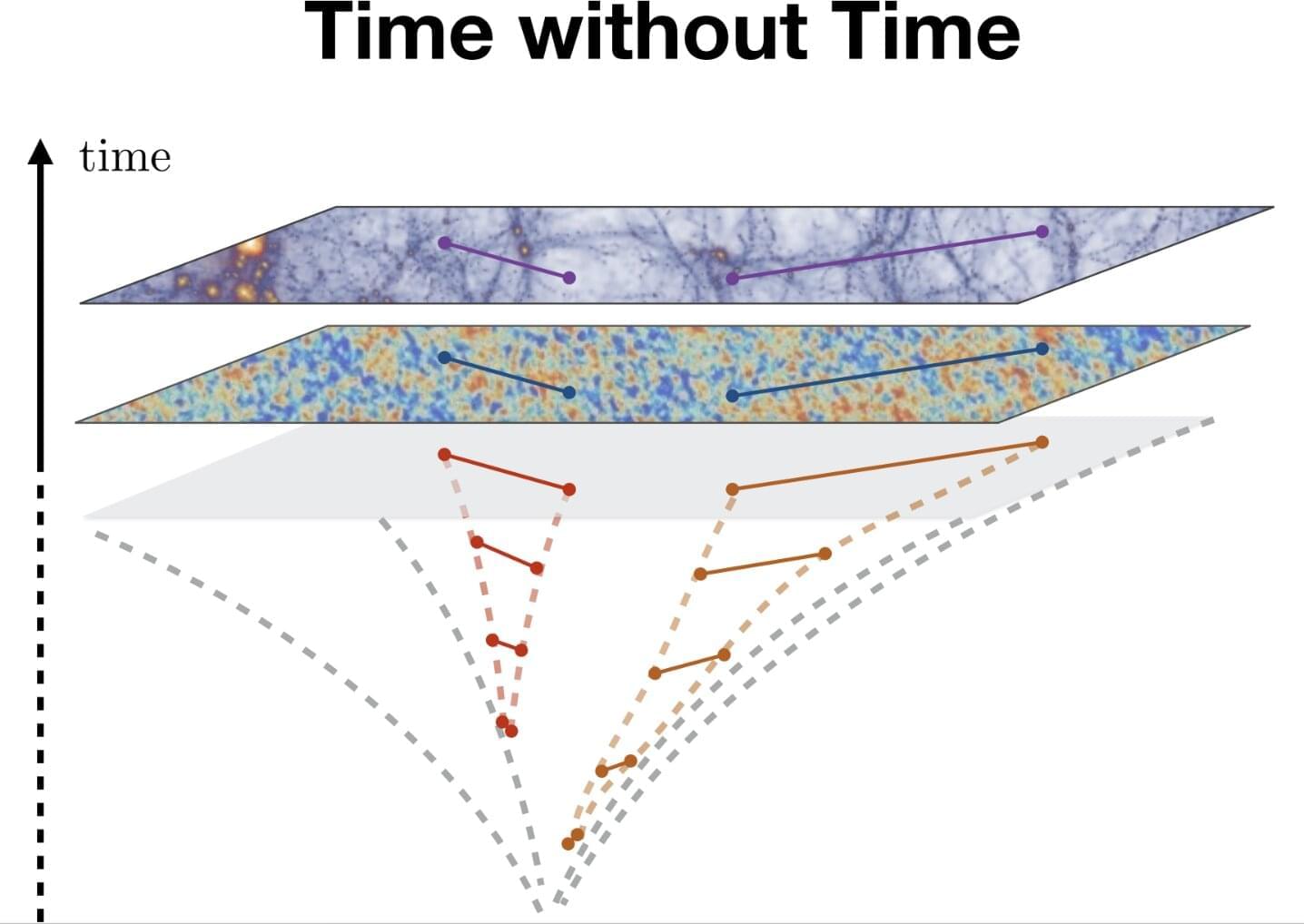

To study the origin and evolution of the universe, physicists rely on theories that describe the statistical relationships between different events or fields in spacetime, broadly referred to as cosmological correlations. Kinematic parameters are essentially the data that specify a cosmological correlation—the positions of particles, or the wavenumbers of cosmological fluctuations.

Changes in cosmological correlations influenced by variations in kinematic parameters can be described using so-called differential equations. These are a type of mathematical equation that connect a function (i.e., a relationship between an input and an output) to its rate of change. In physics, these equations are used extensively as they are well-suited for capturing the universe’s highly dynamic nature.

Researchers at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, the Leung Center for Cosmology and Particle Astrophysics in Taipei, Caltech’s Walter Burke Institute for Theoretical Physics, the University of Chicago, and the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa recently introduced a new perspective to approach equations describing how cosmological correlations are affected by smooth changes in kinematic parameters.