A novel beam diagnostic instrument developed by researchers in the University of Liverpool’s QUASAR Group has been approved for use in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the world’s most powerful particle accelerator.

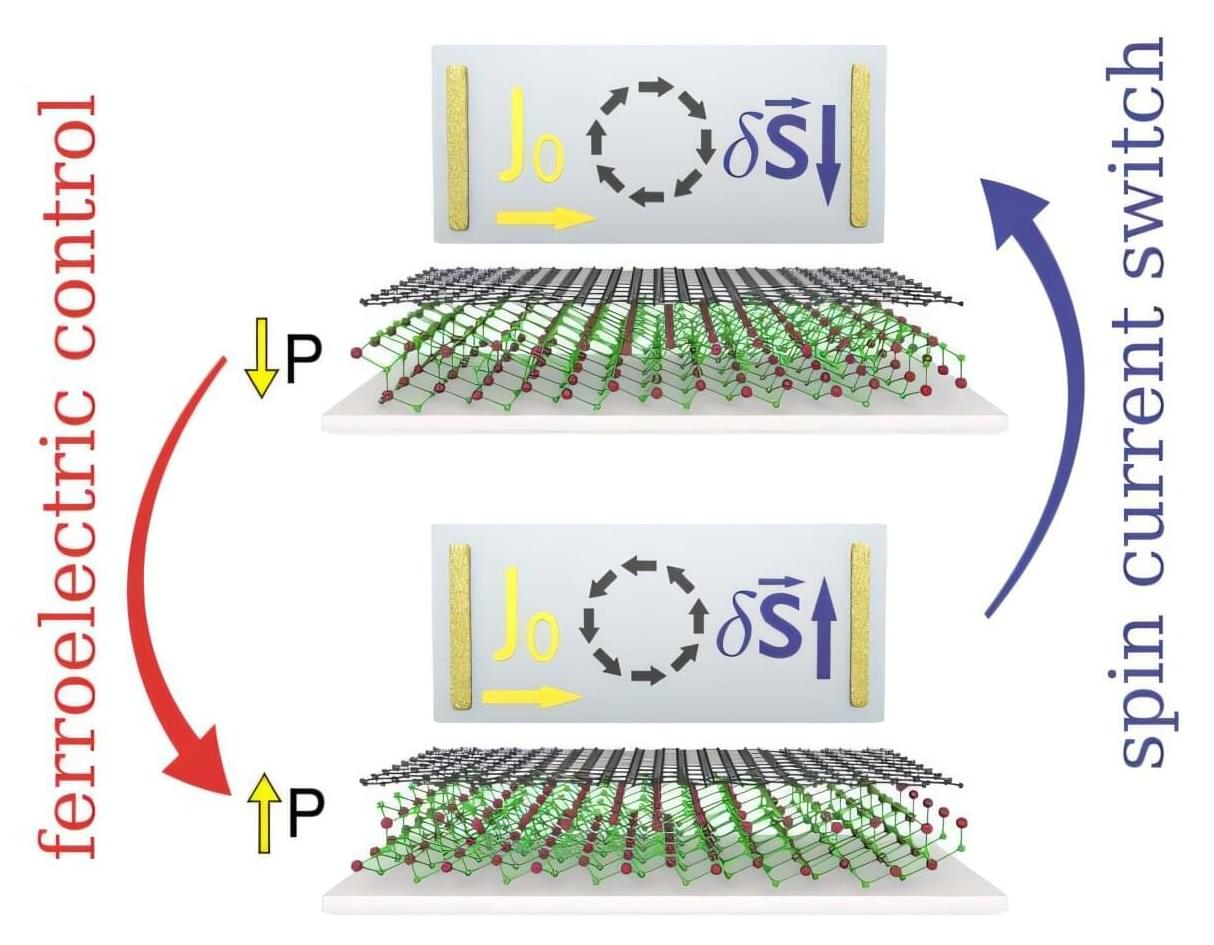

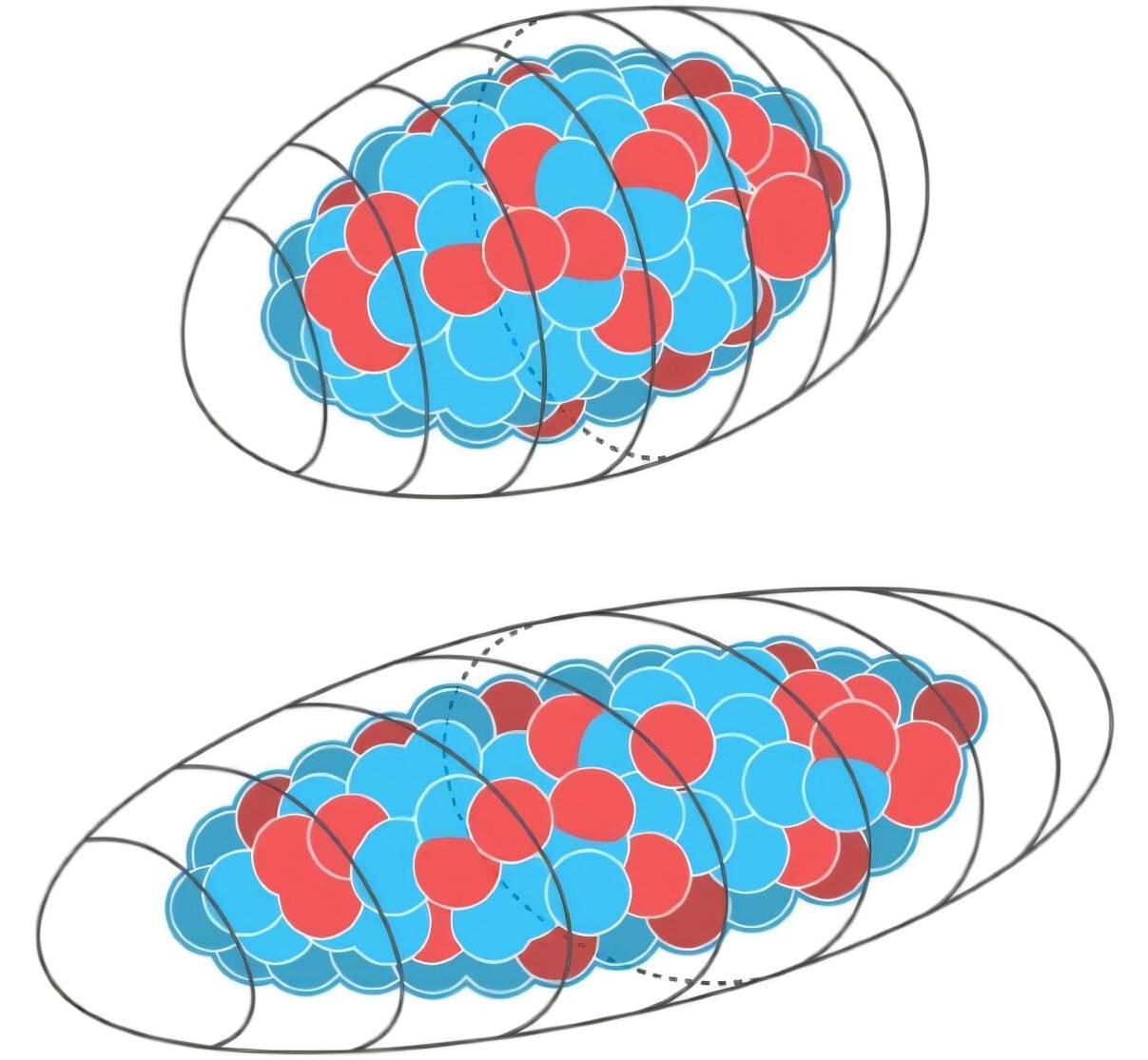

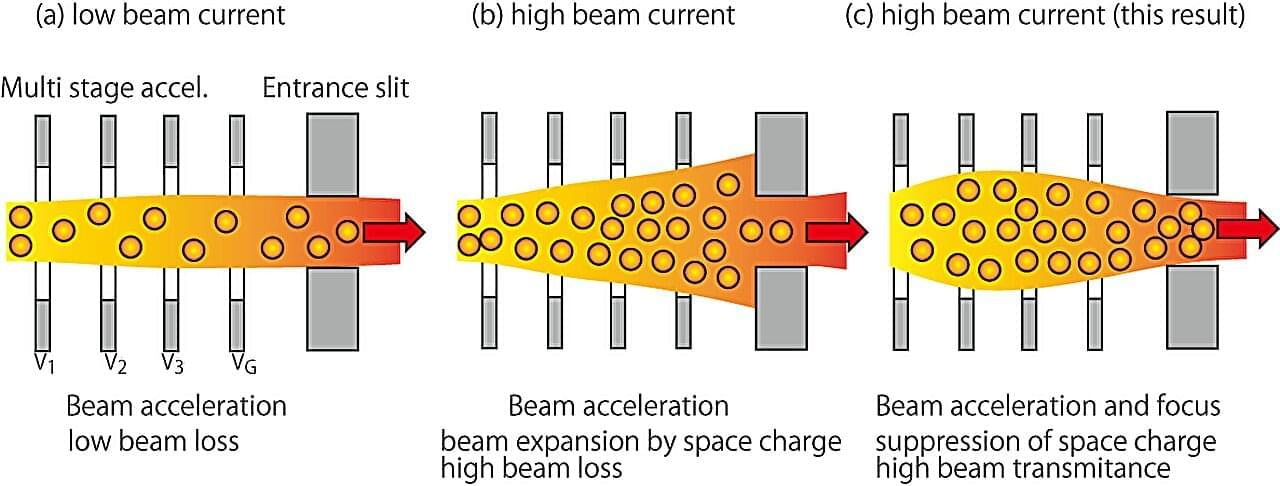

The new device, known as the Beam Gas Curtain (BGC) monitor, addresses one of the toughest challenges in modern accelerator physics: measuring the properties of very high-energy particle beams without disturbing them.

It has now been cleared for continuous operation (~2,000 hours per year).