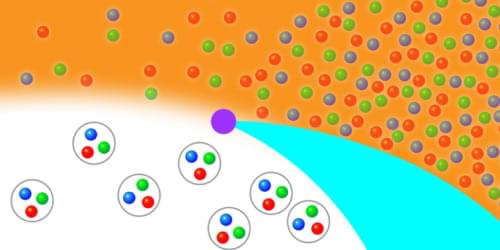

The future of computing lies in the surprising world of quantum physics, where the rules are much different from the ones that power today’s devices. Quantum computers promise to tackle problems too complex for even the fastest supercomputers running on silicon chips. To make this vision real, scientists around the world are searching for new quantum materials with unusual, almost otherworldly properties.

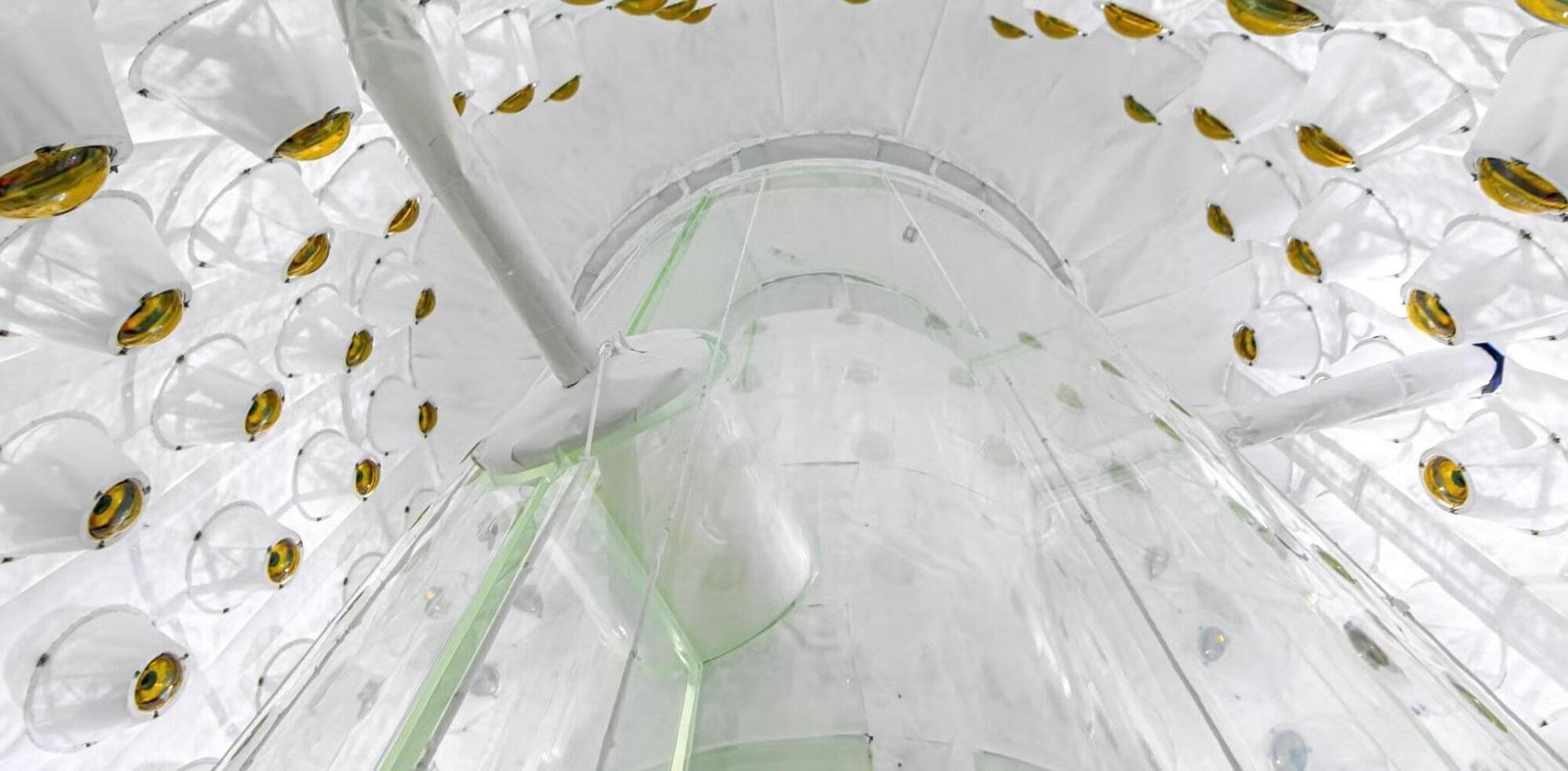

One of the more intriguing candidates is called a quantum spin liquid—a state of matter where electron spins never settle down, even at the coldest temperatures in the universe. To date, however, preparing such a quantum state in a lab has proven stubbornly elusive. In a collaborative project with multiple institutions, scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory now report coming tantalizingly closer.

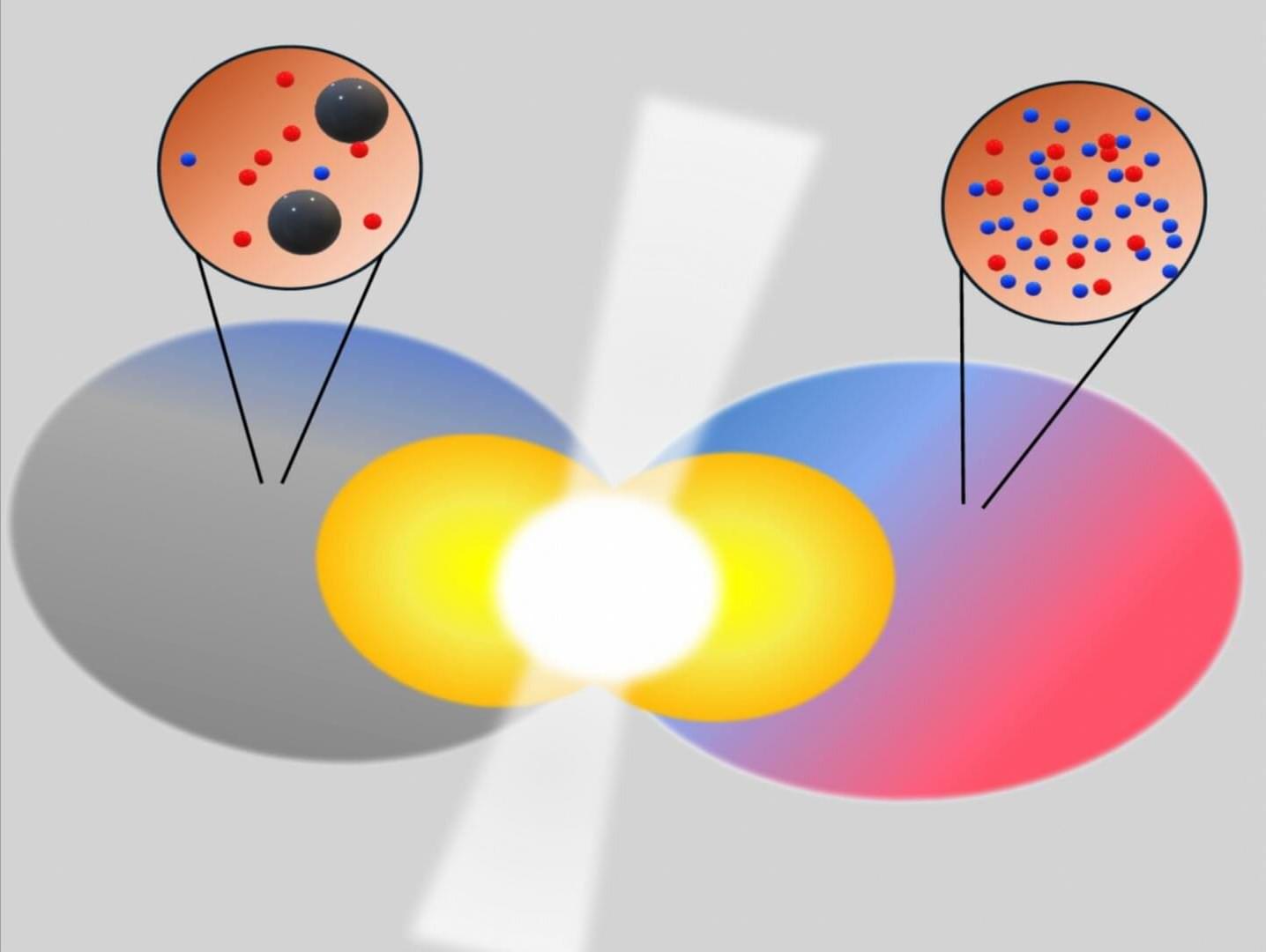

As explained by Argonne Senior Physicist and Group Leader Daniel Haskel, in these materials, it’s not atoms that stay fluid as in an ordinary liquid, but the tiny magnetic orientations—or spins—of electrons. Each spin wants to “get along” with its neighbors by aligning in a way that keeps everyone content. But when the spins are pushed closer together under pressure, satisfying every neighbor becomes impossible.