The observation of elusive, exotic particles is the key objective of countless studies, as it could open new avenues for research, while also improving present knowledge of the matter contained in the universe and its underlying physics. The quark model, a theoretical model introduced in 1964, predicted the existence of elementary subatomic particles known as quarks in their different configurations.

Quarks and antiquarks (the anti-matter equivalent of quarks) are predicted to be constituents of various subatomic particles. These include “conventional” particles, such as mesons and baryons, as well as more complex particles made up of four or five quarks (i.e., tetraquarks and pentaquarks, respectively).

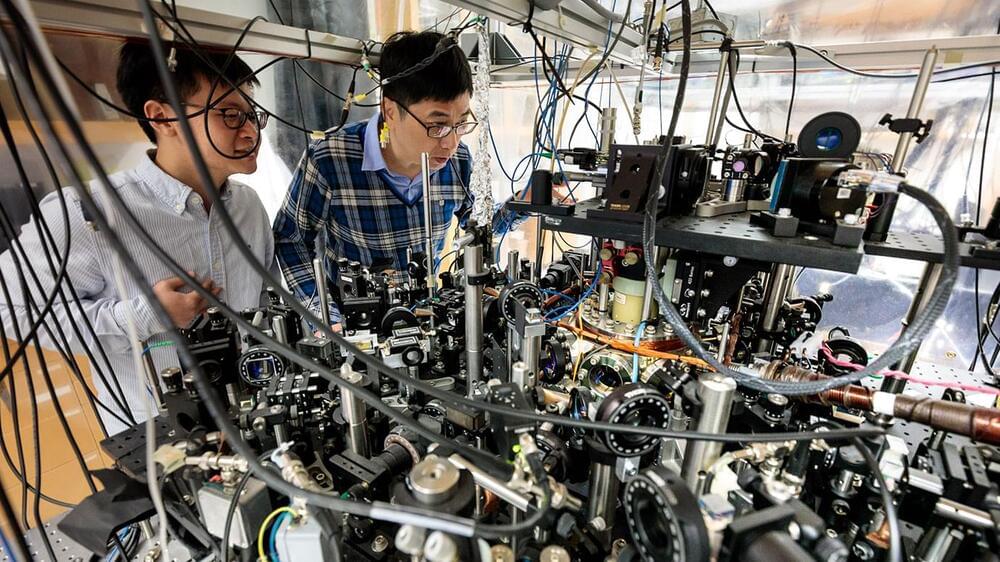

The Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) experiment, a research effort involving a large group of researchers at different institutes worldwide, has been trying to observe some of these fascinating particles for over a decade, using data collected at CERN’s LHC particle collider in Switzerland. In a recent paper published in Physical Review Letters, they reported the very first observation of a doubly charged tetraquark and its neutral partner.