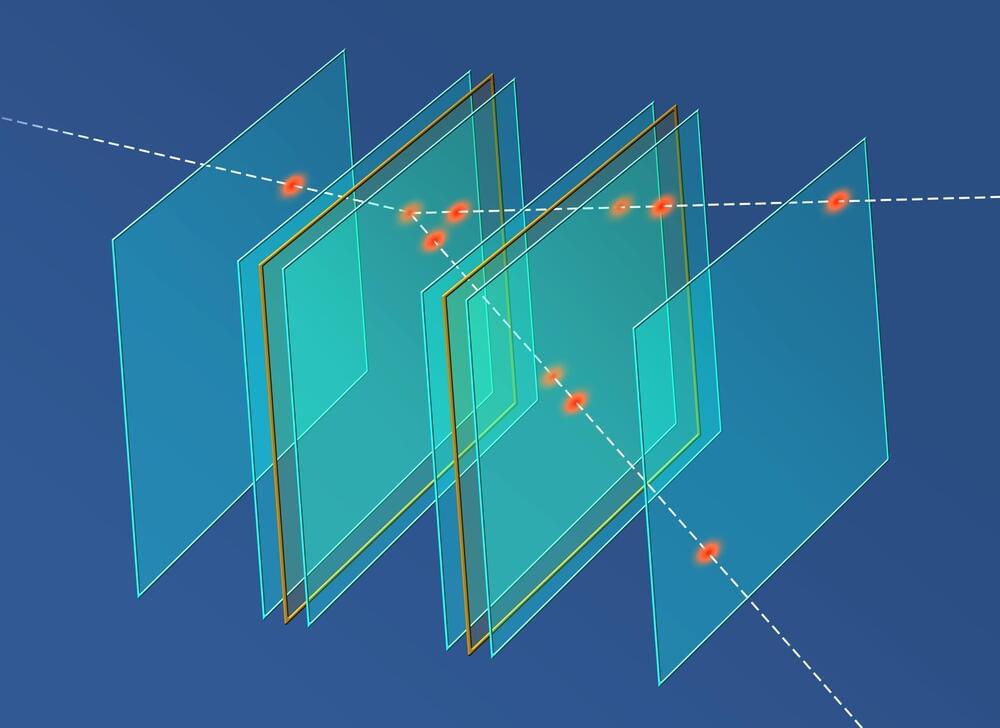

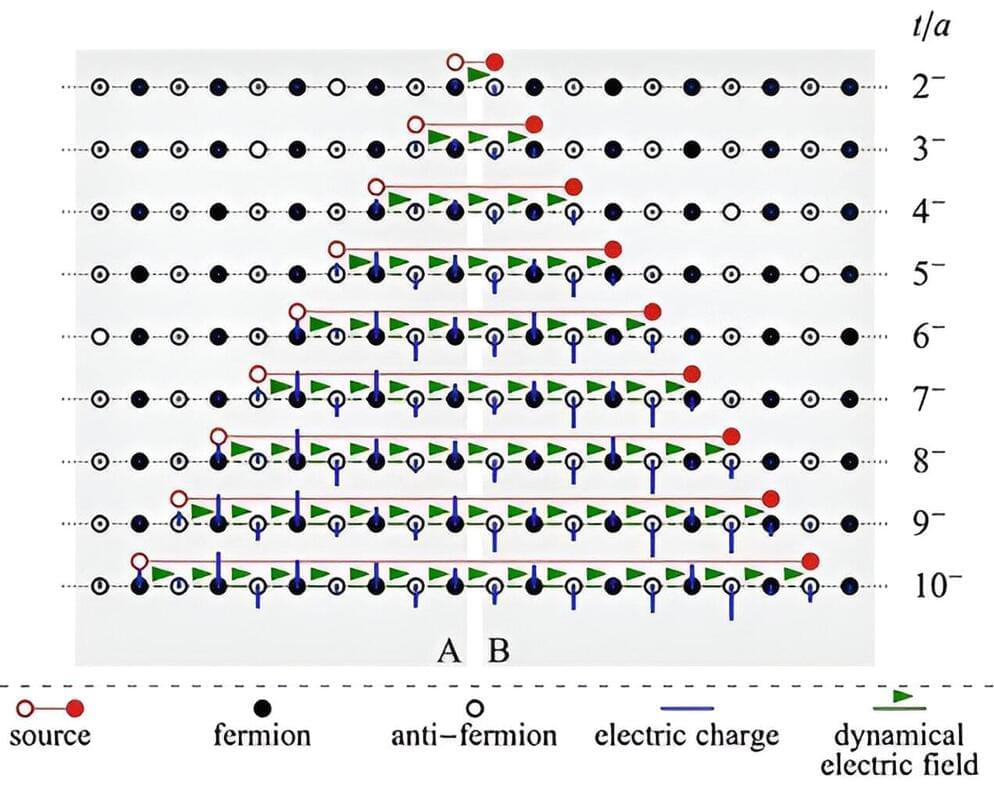

Particles colliding in accelerators produce numerous cascades of secondary particles. The electronics processing the signals avalanching in from the detectors then have a fraction of a second in which to assess whether an event is of sufficient interest to save it for later analysis. In the near future, this demanding task may be carried out using algorithms based on AI, the development of which involves scientists from the Institute of Nuclear Physics of the PAS.