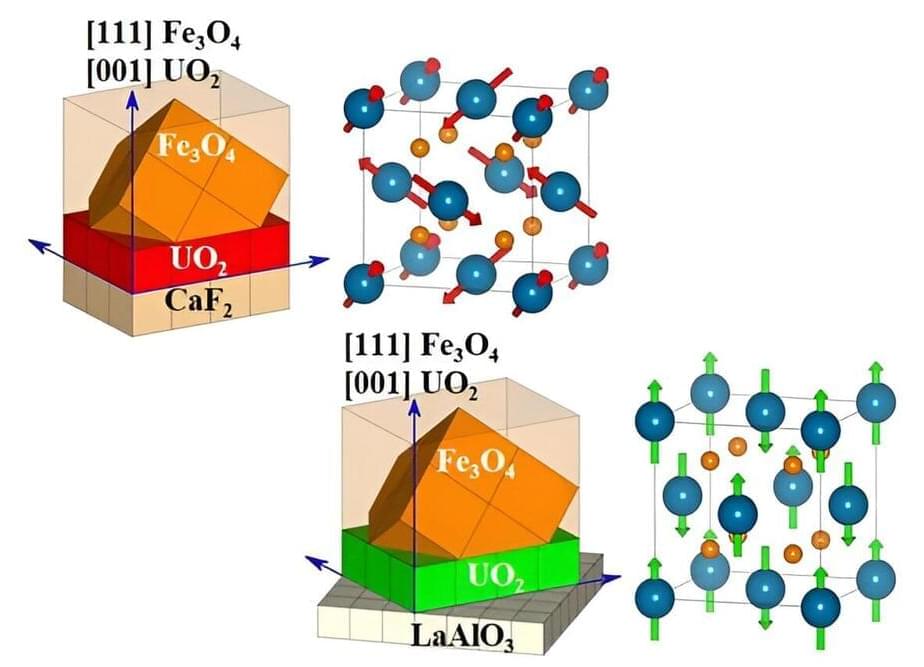

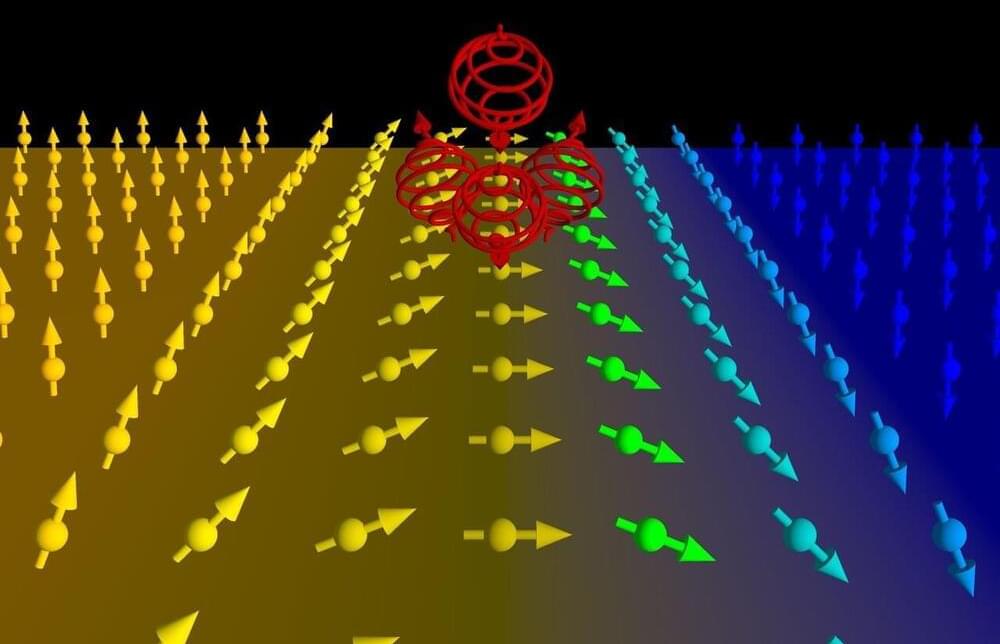

A joint research project of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU), the University of Siegen, Forschungszentrum Jülich, and the Elettra Synchrotron Trieste has achieved a new milestone for the ultra-fast control of magnetism. The international team has been working on magnetization configurations that exhibit chiral twisting. Chirality is a symmetry breaking, which occurs, for example, in nature in molecules that are essential for life. Chirality is also referred to as handedness, since hands are an everyday example of two items that—arranged in a mirror-inverted manner—cannot be superimposed onto each other. Magnetization configurations with a fixed chirality are currently investigated intensively due to their fascinating properties such as enhanced stability and efficient manipulation by current. These magnetic textures thus promise applications in the field of ultrafast chiral spintronics, for example in ultrafast writing and controlling of chiral topological magnetic objects such as magnetic skyrmions, i.e., specially twisted magnetization configurations with exciting properties.

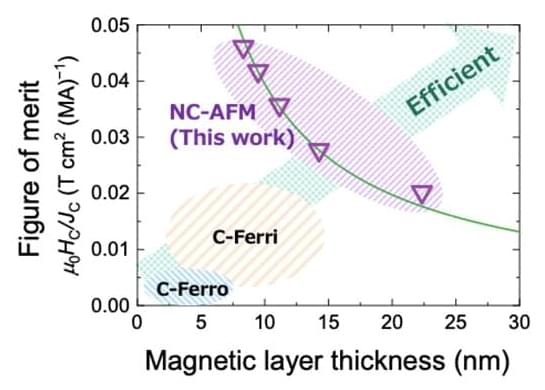

The new insights published in Nature Communications shed light on the ultrafast dynamics after optical excitation of chiral spin structures compared to collinear spin structures. According to the researchers’ findings, the chiral order restores faster compared to the collinear order after excitation by an infrared laser.

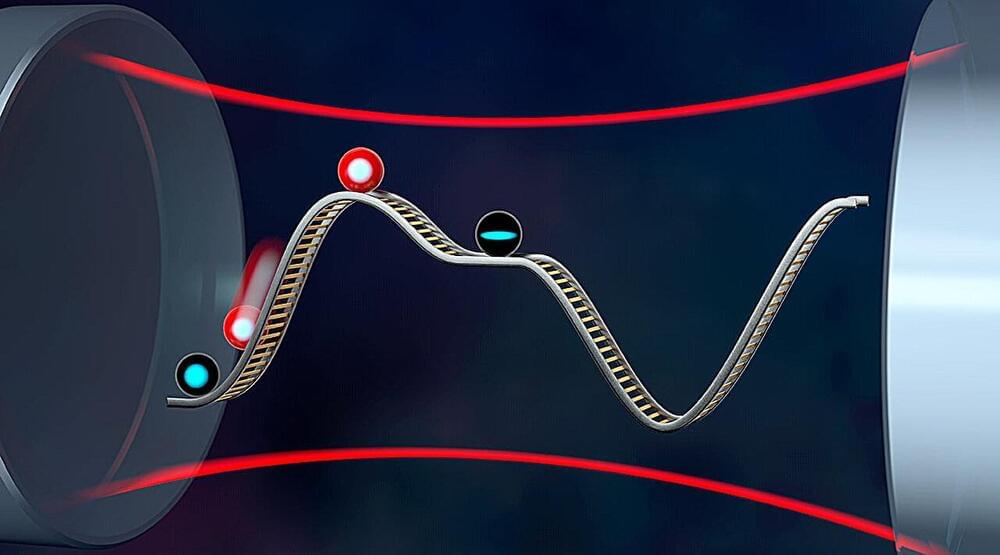

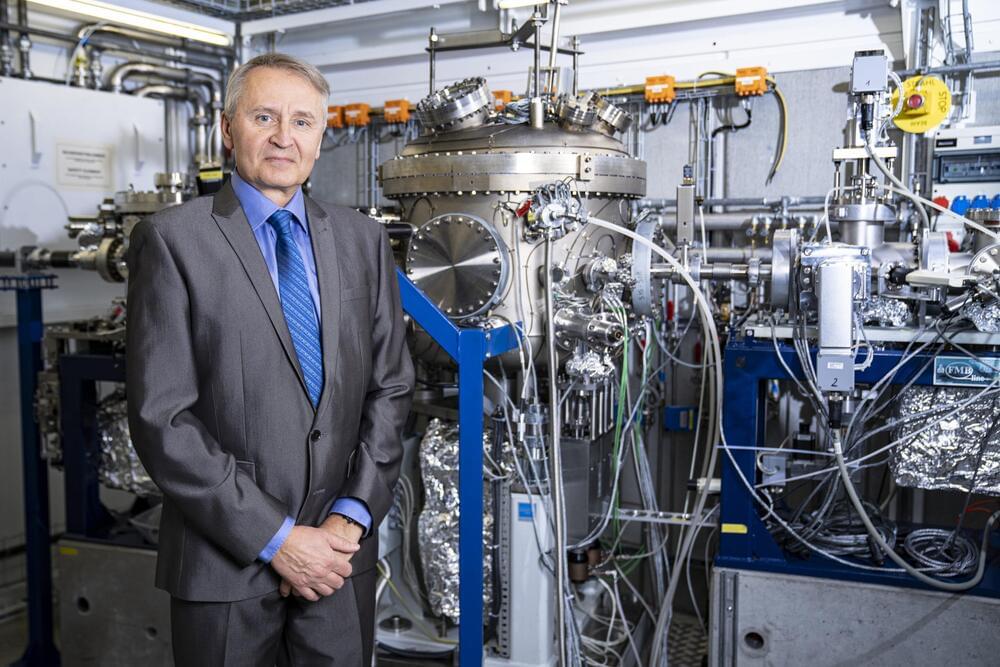

The research team performed small angle X-ray scattering experiments on magnetic thin film samples stabilizing chiral magnetic configurations at the free electron laser (FEL) facility FERMI in Trieste in Italy. The facility provides the unique possibility to study the magnetization dynamics with femtosecond time resolution by using circular left polarized or right polarized light. The results indicate a faster recovery of chiral order compared to collinear magnetic order dynamics, which means that twists are more stable than straight magnetic configurations.