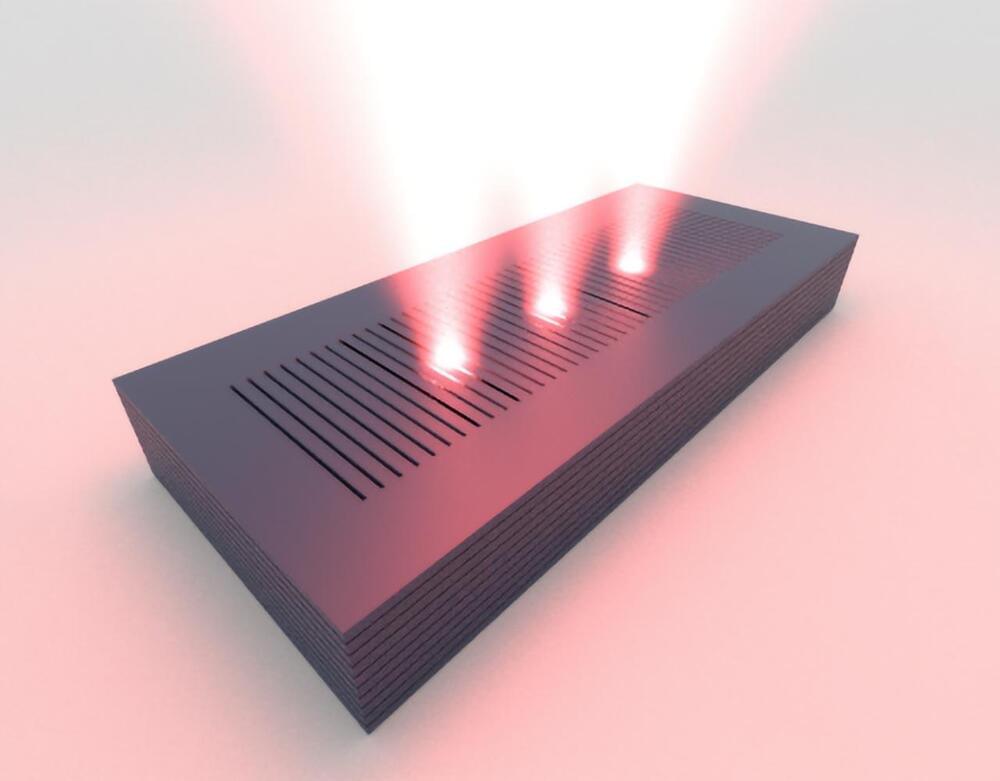

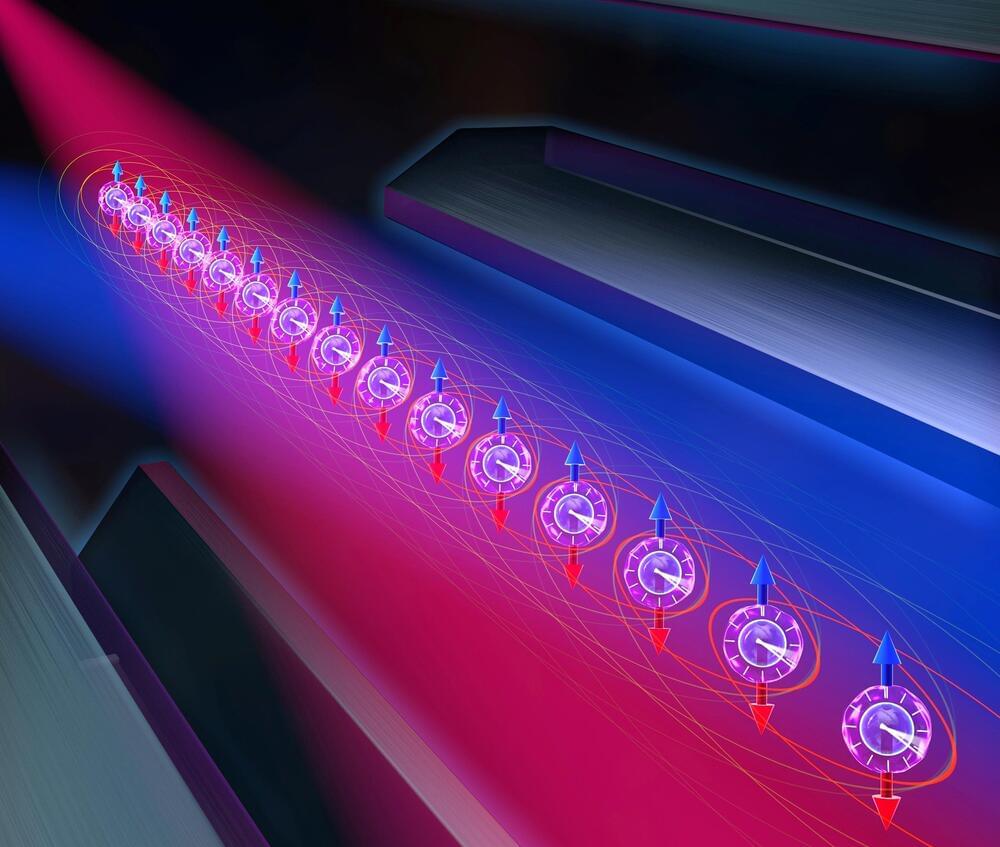

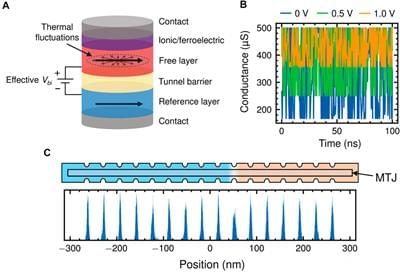

Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) combine the generalizability of deep neural networks (DNNs) with a rigorous quantification of predictive uncertainty, which mitigates overfitting and makes them valuable for high-reliability or safety-critical applications. However, the probabilistic nature of BNNs makes them more computationally intensive on digital hardware and so far, less directly amenable to acceleration by analog in-memory computing as compared to DNNs. This work exploits a novel spintronic bit cell that efficiently and compactly implements Gaussian-distributed BNN values. Specifically, the bit cell combines a tunable stochastic magnetic tunnel junction (MTJ) encoding the trained standard deviation and a multi-bit domain-wall MTJ device independently encoding the trained mean. The two devices can be integrated within the same array, enabling highly efficient, fully analog, probabilistic matrix-vector multiplications. We use micromagnetics simulations as the basis of a system-level model of the spintronic BNN accelerator, demonstrating that our design yields accurate, well-calibrated uncertainty estimates for both classification and regression problems and matches software BNN performance. This result paves the way to spintronic in-memory computing systems implementing trusted neural networks at a modest energy budget.

The powerful ability of deep neural networks (DNNs) to generalize has driven their wide proliferation in the last decade to many applications. However, particularly in applications where the cost of a wrong prediction is high, there is a strong desire for algorithms that can reliably quantify the confidence in their predictions (Jiang et al., 2018). Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) can provide the generalizability of DNNs, while also enabling rigorous uncertainty estimates by encoding their parameters as probability distributions learned through Bayes’ theorem such that predictions sample trained distributions (MacKay, 1992). Probabilistic weights can also be viewed as an efficient form of model ensembling, reducing overfitting (Jospin et al., 2022). In spite of this, the probabilistic nature of BNNs makes them slower and more power-intensive to deploy in conventional hardware, due to the large number of random number generation operations required (Cai et al., 2018a).