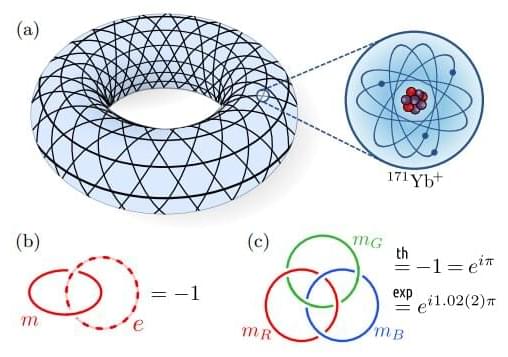

In a development that could make quantum computers less prone to errors, a team of physicists from Quantinuum, California Institute of Technology and Harvard University has created a signature of non-Abelian anyons (nonabelions) in a special type of quantum computer. The team has published their results on the arXiv preprint server.

As scientists work to design and build a truly useful quantum computer, one of the difficulties is trying to account for errors that creep in. In this new effort, the researchers have looked to anyons for help.

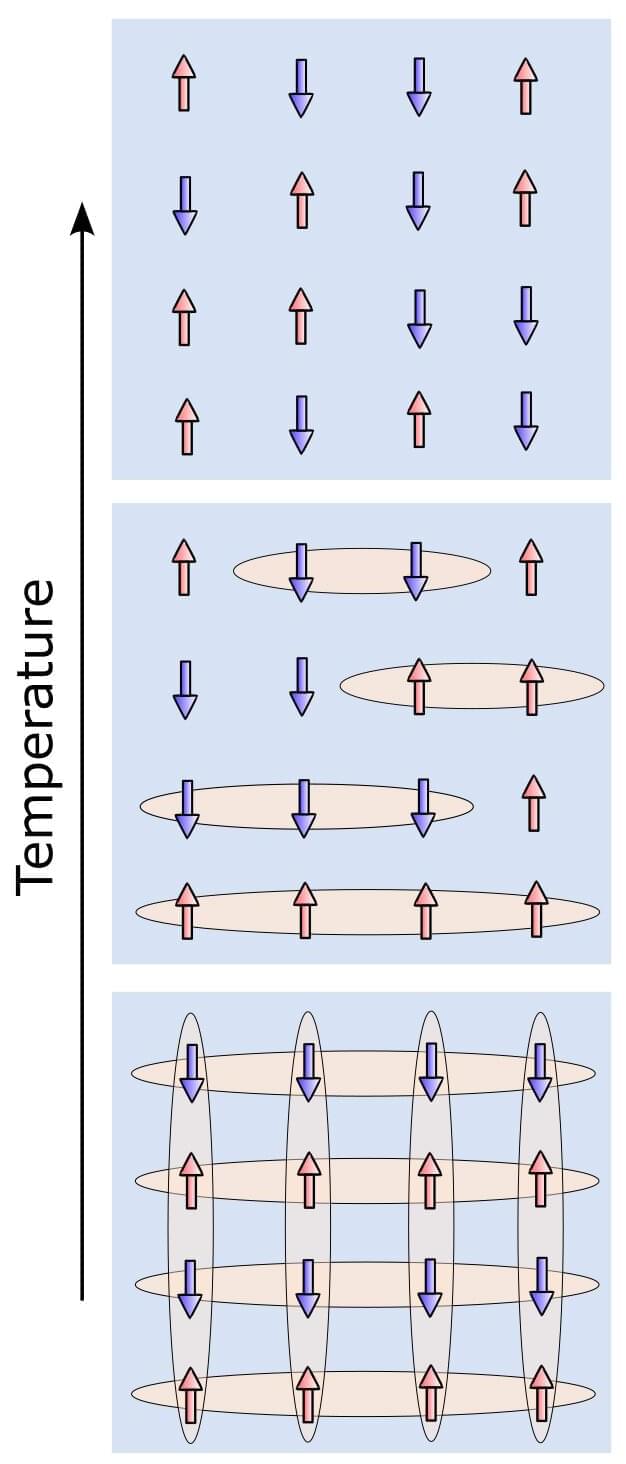

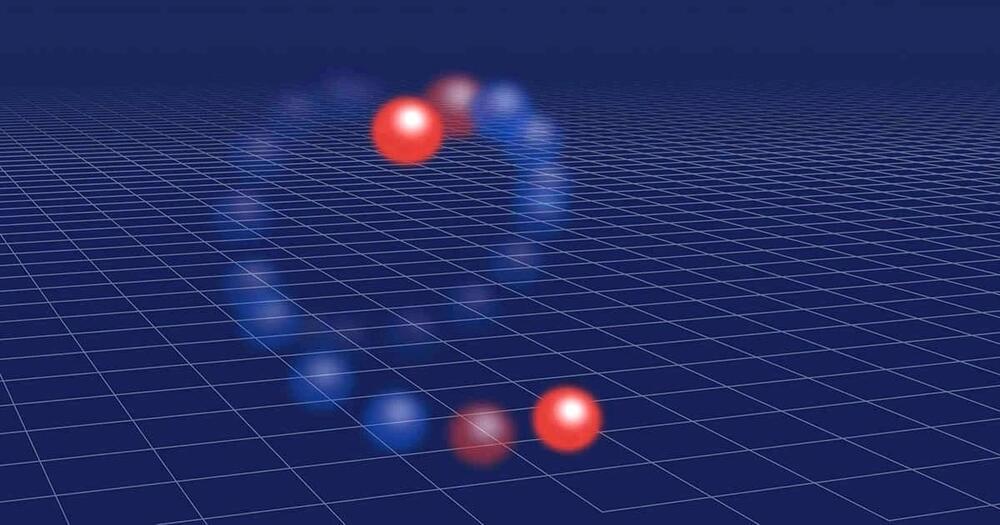

Anyons are quasiparticles that exist in two dimensions. They are not true particles, but instead exist as vibrations that act like particles—certain groups of them are called nonabelions. Prior research has found that nonabelions have a unique and useful property—they remember some of their own history. This property makes them potentially useful for creating less error-prone quantum computers. But creating, manipulating and doing useful things with them in a quantum computer is challenging. In this new work, the team have come close by creating a physical simulation of nonabelions in action.