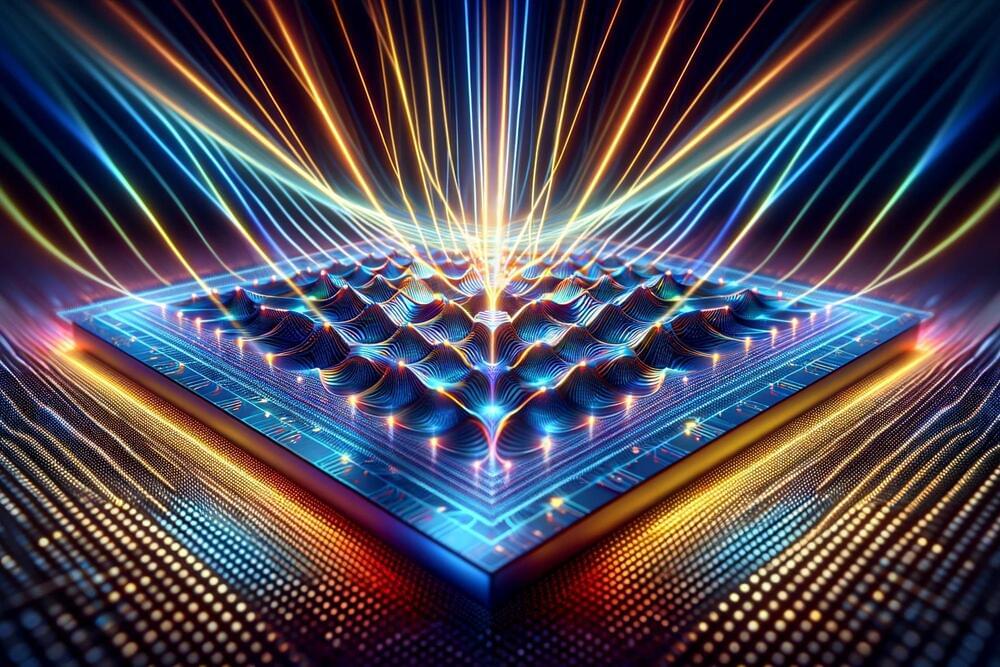

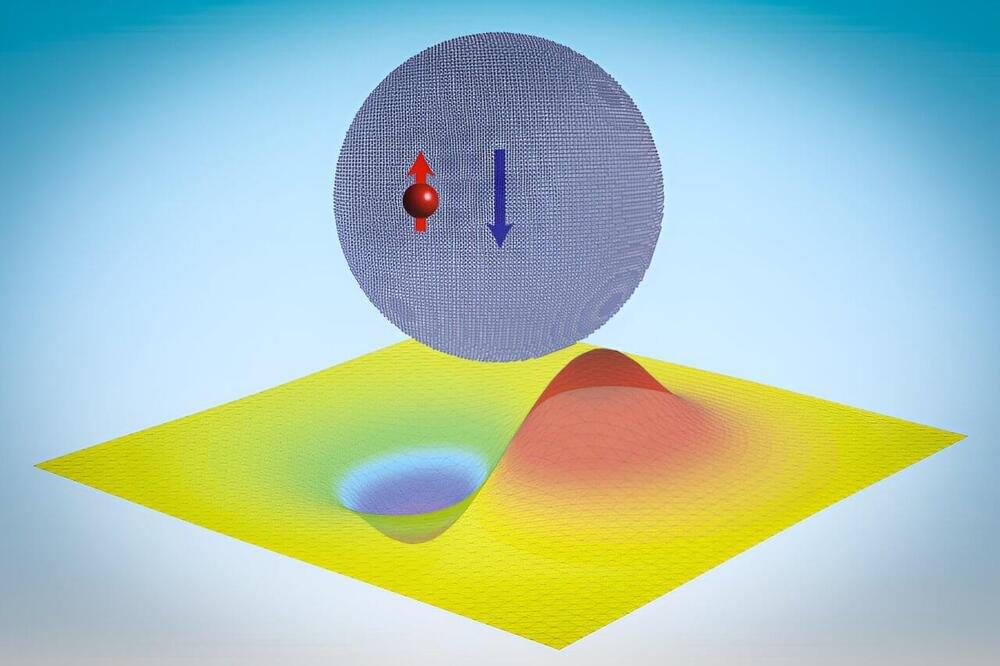

Dielectric metasurfaces, known for their low loss and subwavelength scale, are revolutionizing optical systems by allowing multidimensional light modulation. Researchers have now innovated in this field by developing a liquid crystal-based dielectric metasurface that streamlines manufacturing and enhances device performance.

Dielectric metasurfaces represent one of the cutting-edge research and application directions in the current optical field. They not only possess the advantage of low loss but also enable the realization of device thicknesses at subwavelength scales. Moreover, they can freely modulate light in multiple dimensions such as amplitude, phase, and polarization. This capability, which traditional optics lacks, holds significant importance for the integration, miniaturization, and scaling of future optical systems. Consequently, dielectric metasurfaces have attracted increasing industrial attention.

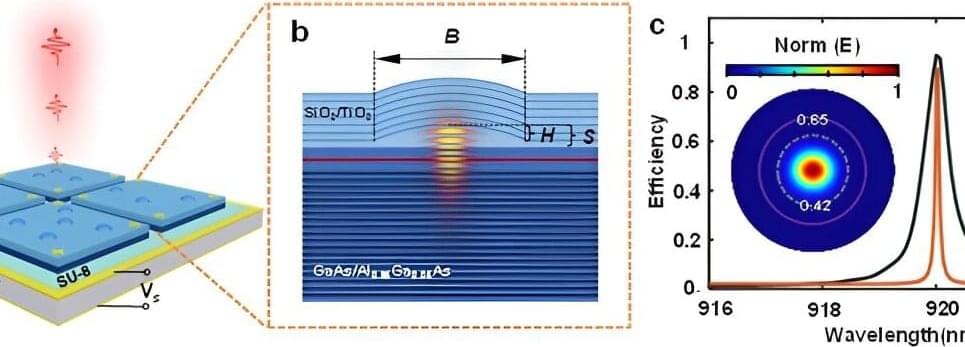

In this study, Professor Daping Chu’s team at the University of Cambridge developed a novel liquid crystal-based tunable dielectric metasurface. By leveraging the dielectric metasurface’s inherent alignment effect on liquid crystals on top of its electrically controllable properties, the need for liquid crystal alignment layer materials and related processes is eliminated, thus saving device manufacturing time and costs. This has practical implications for devices such as liquid crystal on silicon (LCoS).