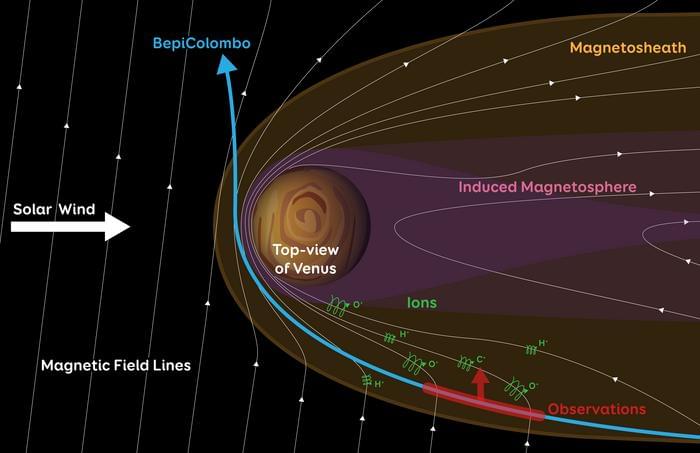

How much of Venus’s atmosphere is being stripped by the Sun, and what can this tell us about how the planet lost its water long ago? This is what a recent study published in Nature Astronomy hopes to address as a team of international researchers examined data obtained from a 2021 Venus flyby by the BepiColombo spacecraft, which is a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan Aerospace and Exploration Agency (JAXA) currently en route to Mercury. This study holds the potential to help researchers better understand the formation and evolution of planetary atmospheres, both within our solar system and beyond.

“Characterizing the loss of heavy ions and understanding the escape mechanisms at Venus is crucial to understand how the planet’s atmosphere has evolved and how it has lost all its water,” said Dr. Dominique Delcourt, who is a CNRS researcher at the Plasma Physics Laboratory (LPP) and the Principal Investigator of the Mass Spectrum Analyzer (MSA) instrument onboard BepiColombo, and a co-author on the study.

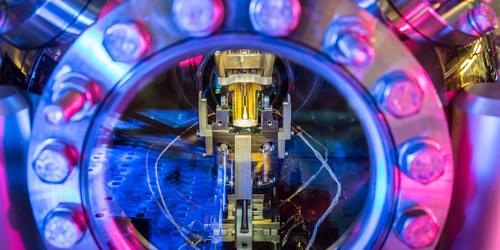

During its journey to Mercury, BepiColombo needs to conduct several gravity assists to slow down enough to enter Mercury’s orbit, with one such gravity assist occurring at Venus on August 10, 2021. During this flyby, BepiColombo passed through Venus’s magnetosheath, which is Venus’s version of a weak magnetic field that is produced by charged particles from the Sun interacting with Venus’s upper atmosphere. Over the course of 90 minutes, BepiColombo and its powerful instruments successfully measured data on how much atmospheric loss Venus is currently experiencing, which could help researchers better understand the formation and evolution of Venus’s atmosphere, and specifically how the planet lost its water long ago.