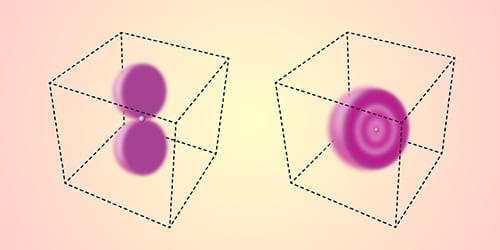

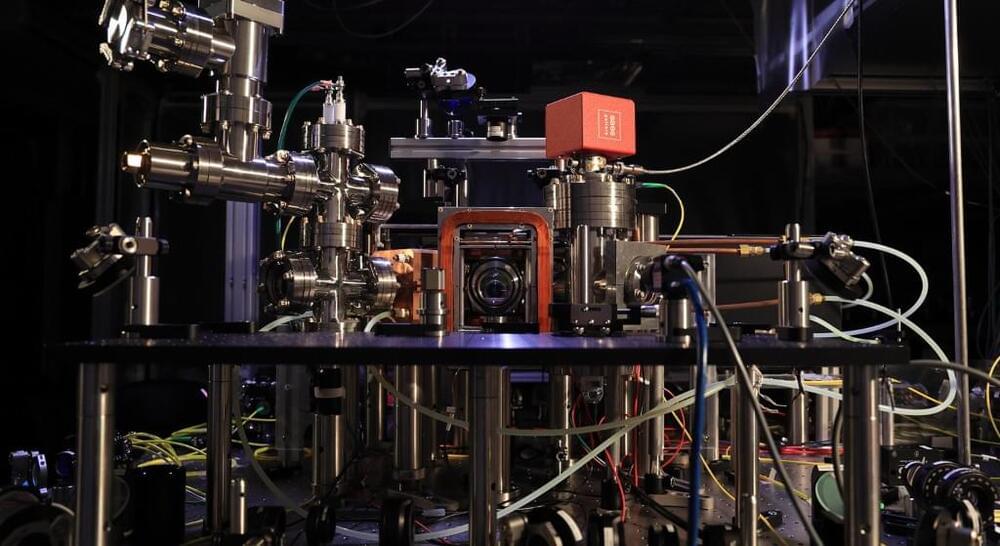

Physicists used to think they had a good idea of the size of the proton. Values derived from measurements of hydrogen’s emission spectrum and from electron-scattering experiments agreed with a proton radius of around 0.88 femtometers (fm). Then, in 2010, confidence was shaken by a spectral measurement that indicated a proton radius of approximately 0.84 fm [1]. In the years since, this “proton radius puzzle” has become even more of a head-scratcher, with some experiments supporting the original estimate and others finding an even greater discrepancy. Simon Scheidegger and Frédéric Merkt at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, have now made precise new measurements of the transition energies between one of hydrogen’s metastable low-energy states and several of its highly excited states [2] (Fig. 1). These measurements allow the researchers to derive some of the atom’s properties, such as its ionization energy, with greater confidence, which should help clear up some of the confusion.

The 2010 study that “shrank the proton” (as the title of the editorial summary in Nature jokingly stated) concerned the 2 S –2 P1/2 Lamb shift [1]. According to Dirac’s predictions, the 2 S and 2 P1/2 levels of atomic hydrogen should be degenerate. The Lamb shift refers to the lifting of this degeneracy by quantum electrodynamic (QED) effects, the largest contribution being the electron “self-energy” due to interactions with virtual photons. Once this and other QED effects are accounted for, a tiny shift of the bound-state energy levels remains, which can be attributed to the proton’s finite size. By measuring this residual energy shift, one can determine the proton radius directly. The authors of the 2010 study did so using hydrogen atoms in which the electron was replaced by its heavier cousin, the muon, since the finite-size effect is stronger in this system.

Ever since that surprise result, researchers have tried to pin down the proton radius both directly, via the finite-size effect, and indirectly, via the Rydberg constant. The Rydberg constant relates an atom’s energy levels to other physical constants and is one of the key inputs used in calculations of the proton radius. Determining its value requires painstaking measurements of the transition energies between hydrogen’s various states. Several groups have made monumental efforts in this regard, but the values they derive for the proton radius have been all over the place. A 2018 measurement of the 1 S –3 S transition by a group in France gave a value of about 0.88 fm [3], a 2019 measurement of the classic Lamb shift (this time in regular hydrogen) by a group in Canada came up with a value of about 0.833 fm [4], and a 2017 measurement of the 2 S –4 P transition by a group in Germany suggested a similarly low value of about 0.834 fm [5]. In 2020, the group in Germany arrived at a slightly higher value of 0.848 fm [6]. In 2022, finally, from measurements of the 2 S –8 D transition, a group at Colorado State University proposed a “compromise value” of about 0.86 fm [7].