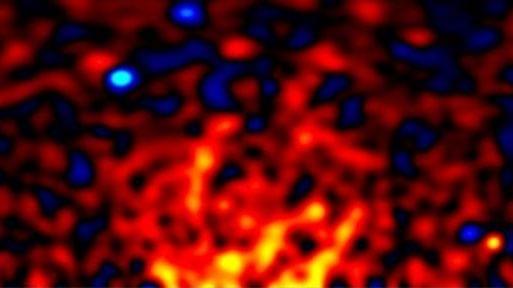

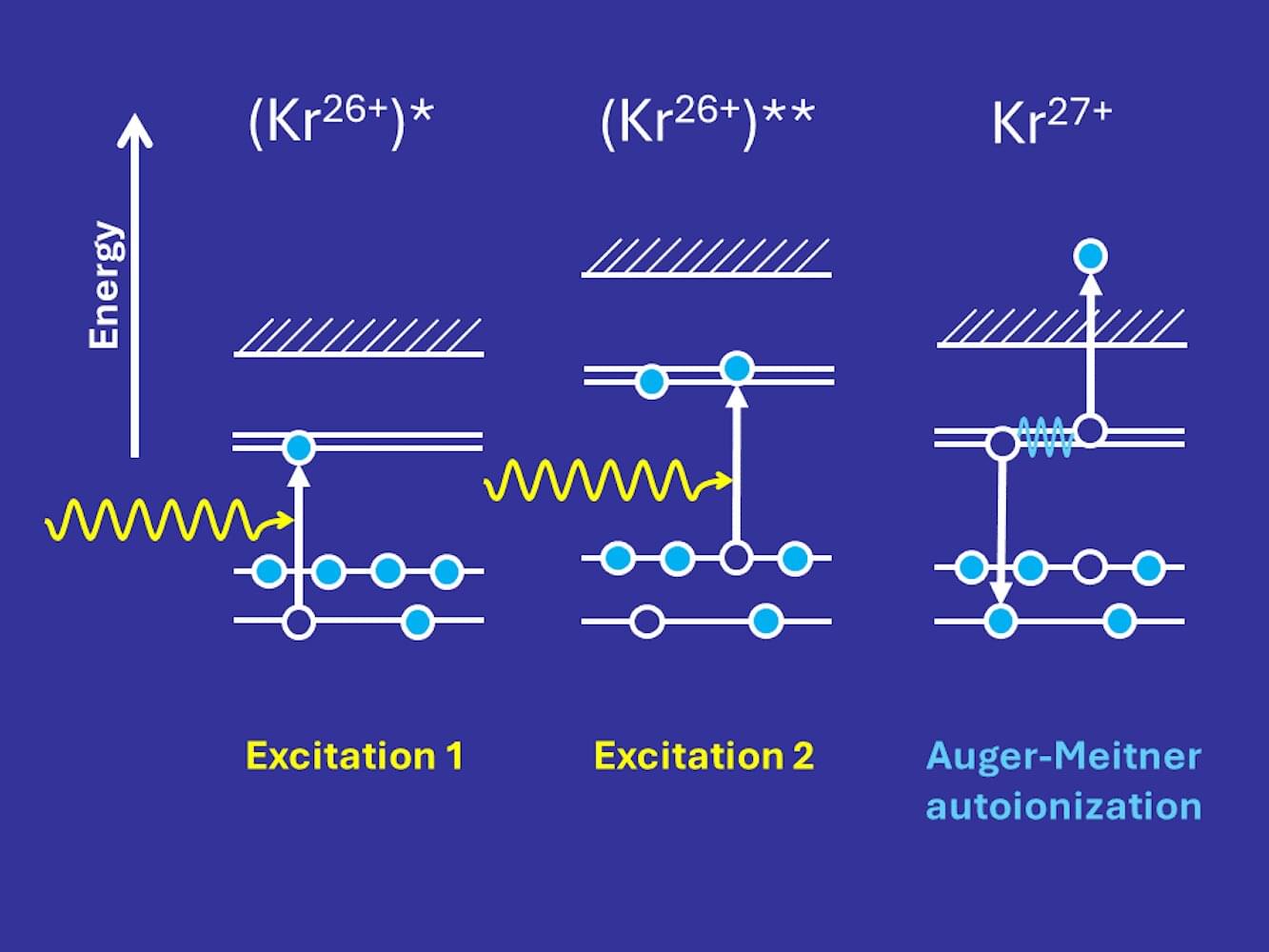

Speed matters. When an X-ray photon excites an atom or ion, making a core electron jump onto a higher energy level, a short-lived window of opportunity opens. For just a few femtoseconds, before an electron fills the void in the lower energy level, a second photon has the chance to be absorbed by another core electron, creating a doubly excited state.

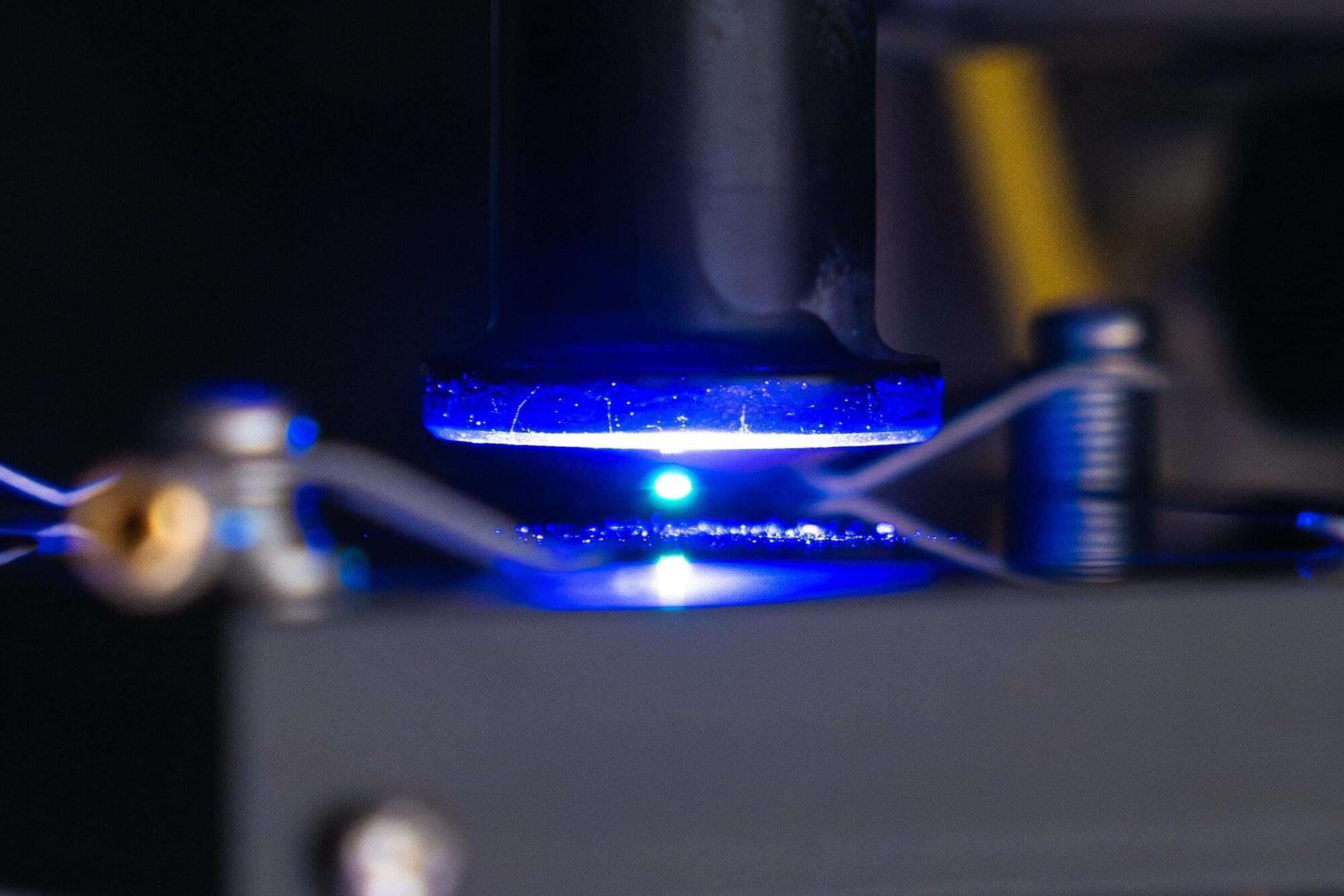

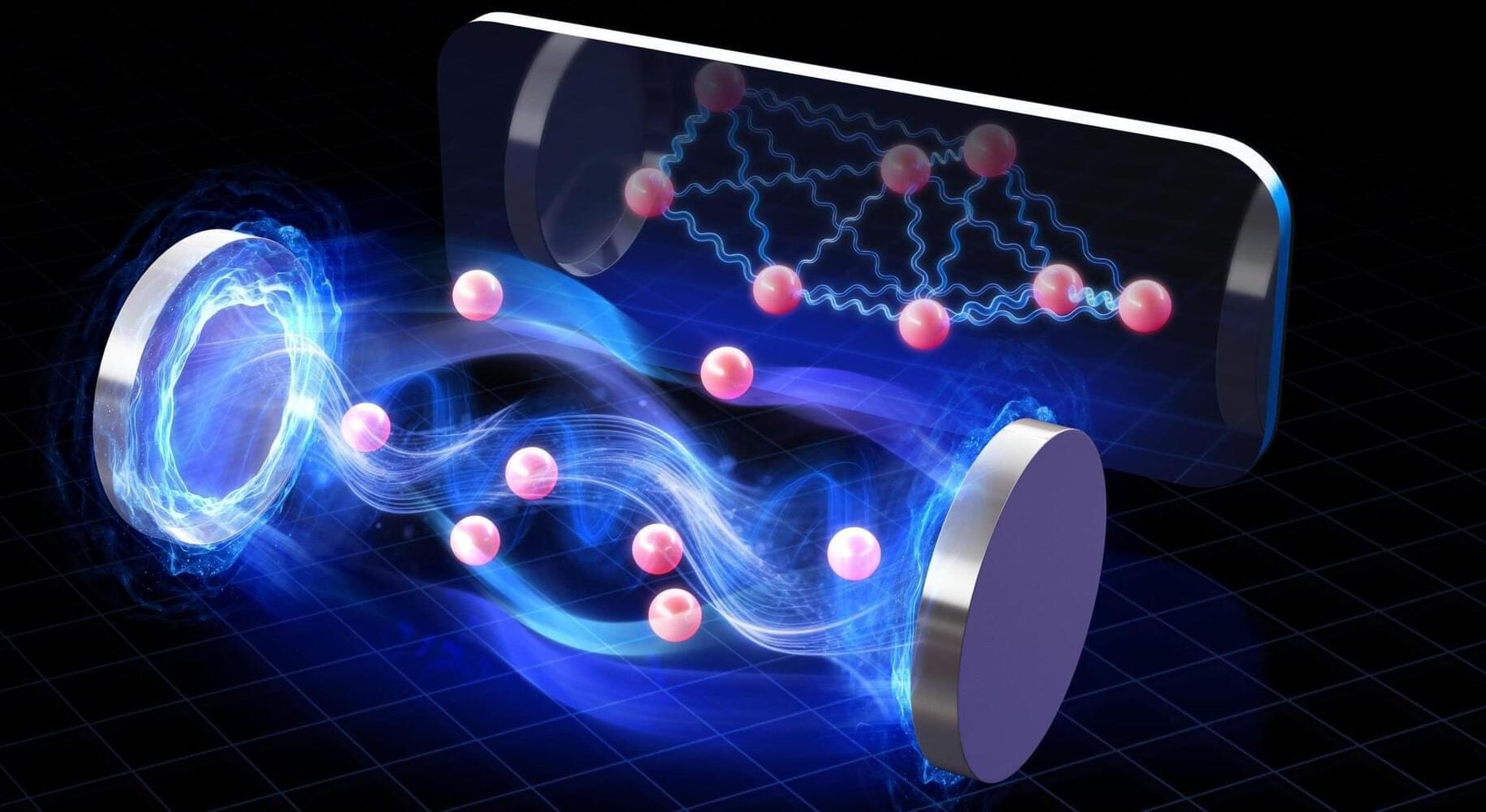

Using 5,000 intense X-ray flashes per second, generated by the European XFEL, an international team of scientists has investigated such double core-hole states in highly ionized krypton, using photons that all had nearly the same energy or color.

For their experiments, scientists from European XFEL and the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics (MPIK) in Heidelberg as well as six other institutions across Germany, Italy, Portugal, and the United States, used highly charged krypton, Kr26+, lacking all but ten of its electrons.