Physics stack exchange has recently been debating the question of the subjectivity of entropy.

I recommend Andrew Steane answer.

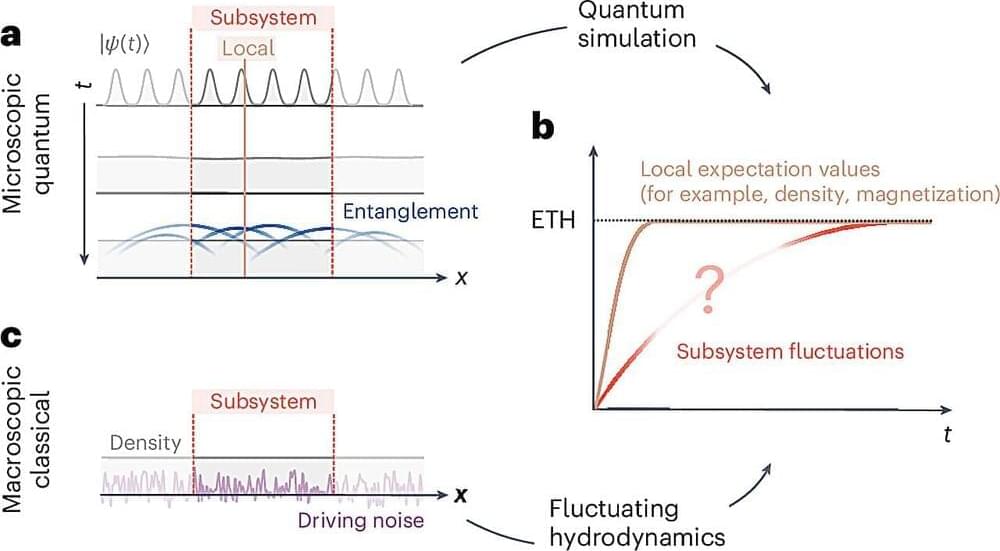

I’m a computer scientist doing some research that touches on basic concepts in statistical mechanics: macrostate, microstate and entropy. The way I’m currently conceiving of it is that the microstate includes all the information to perfectly the describe the state of a system, the macrostate provides some of the information, allowing you to narrow down the possibilities to a subset of states and a distribution over them, and the entropy roughly says how much information is still missing after you specify the macrostate.

From various places online, including this SE thread, I read that the choice of what to put in the macro-description depends on what state variables one is interested in. That SE answer seems to downplay the significance of this, but from my uninformed outsider perspective it seems like a big deal. I could, for example, make the entropy of any system zero if I choose the state variables to be the position and momentum of every particle (let’s just stick to the classical paradigm for now).

From the examples I’ve seen, there are only a few state variables such as temperature and pressure that are even considered, but could/does it ever happen that two different experimenters on the same system have different ‘opinions’ on what the state variables should be, and so calculate totally different values for entropy? If not, is there a satisfying reason why the choice of state variables is not as subjective as it appears?