An ultra-precise measurement of a transition in the hearts of thorium atoms gives physicists a tool to probe the forces that bind the universe.

About 63% of the world population access the internet [Source: Statista] and a majority of them experience the internet through webpages. As such, the general population refers to the internet and the web pages interchangeably. Of course, those in the technology arena do know the difference but may or may not remember when and where the world wide web (WWW) was invented. Without its invention, the internet experience of today will not be the same.

100% of all living creatures experience something automatically and that is their “mass”, interchangeably and inaccurately referred to as “weight” by the general population. Of course, those who remember their physics know the difference. While material mass is taken for granted in general physics, there is a field of physics that tries to explain what gives materials their mass. The existence of the mass-giving field was confirmed when the Higgs boson particle was discovered.

The organization that is behind both the WWW invention and the Higgs boson discovery and many other remarkable inventions is CERN. The World Wide Web was invented in 1989 by Tim Berners-Lee while working at CERN. The existence of the mass-giving field was confirmed in 2012, when the Higgs boson particle was discovered at CERN.

, while an interesting thought experiment, does not seem to account for the fact that many phenomena are materialistic or physical enough to have no resemblance with the qualities we typically attribute to consciousness, such as experience and motive.

Panprotopsychism, by contrast, does not require matter to be intrinsically conscious, only that it be comprised of features equaling consciousness when combined.

If certain kinds of quantum entanglement between particles such as electrons, more aptly described as wavicles, have superposed properties with likeness to the visible light spectrum when arranged amongst molecules and additional corpuscles, mechanisms of superposition may be the basic material unit of qualitative experience. These qualia, as fragments of psychical imagery and feeling, may flit in and out of existence rapidly within the most inorganic conditions, so that components of perception exist on a fundamental level while commonly not giving rise to experience and motive. But when these superpositions are held in prolonged orientations amongst brain matter and in nature generally, consciousness of carbon-based, human and alternative richness can emerge.

With its particles in two places at once, quantum theory strains our common sense notions of how the universe should work. But one group of physicists says we can get reality back if we just redefine its foundations.

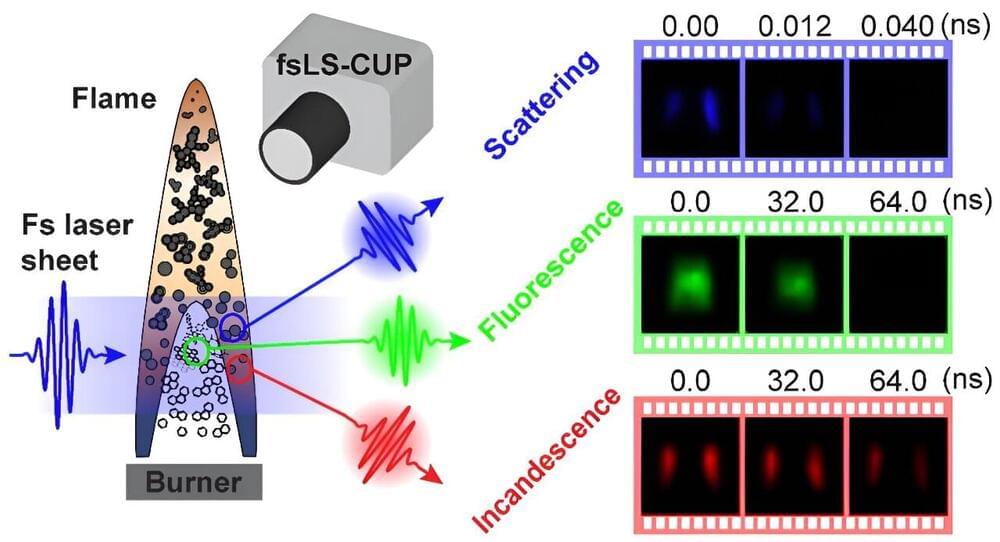

Candle flames and airplane engines produce tiny soot particles from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as their precursors, both of which are harmful to humans and the environment. These carbon-based particles are also common in space, making up 10–12% of interstellar matter, and are becoming valuable for use in electronic devices and sustainable energy. However, the fingerprint signals of soot and PAHs have very short lifespans in flames—lasting only a few billionths to millionths of a second. This brief existence requires very fast cameras to capture their behavior in both space and time.

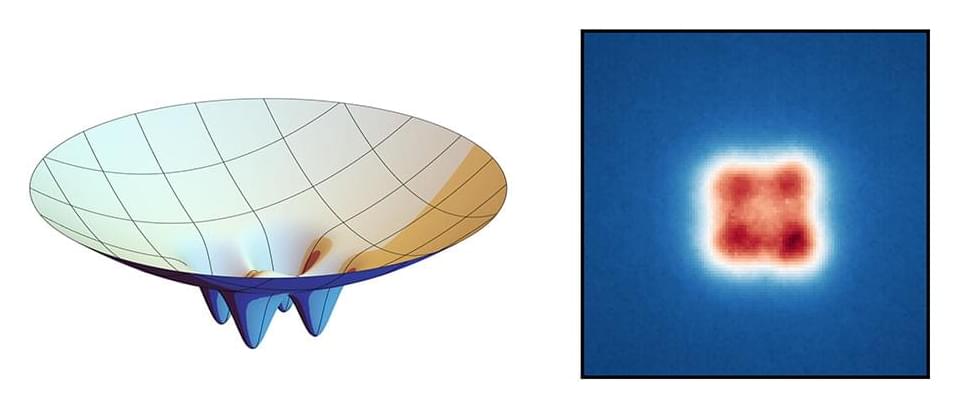

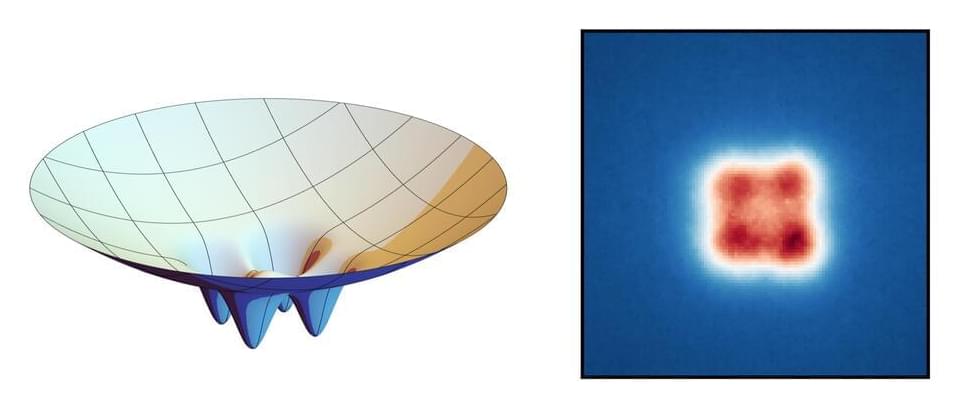

Thousands of light particles can merge into a type of “super photon” under certain conditions. Researchers at the University of Bonn have now been able to use “tiny nano molds” to influence the design of this so-called Bose-Einstein condensate. This enables them to shape the speck of light into a simple lattice structure consisting of four points of light arranged in quadratic form. Such structures could potentially be used in the future to make the exchange of information between multiple participants tap-proof.

The results have now been published in the journal Physical Review Letters (“Bose-Einstein Condensation of Photons in a Four-Site Quantum Ring”).

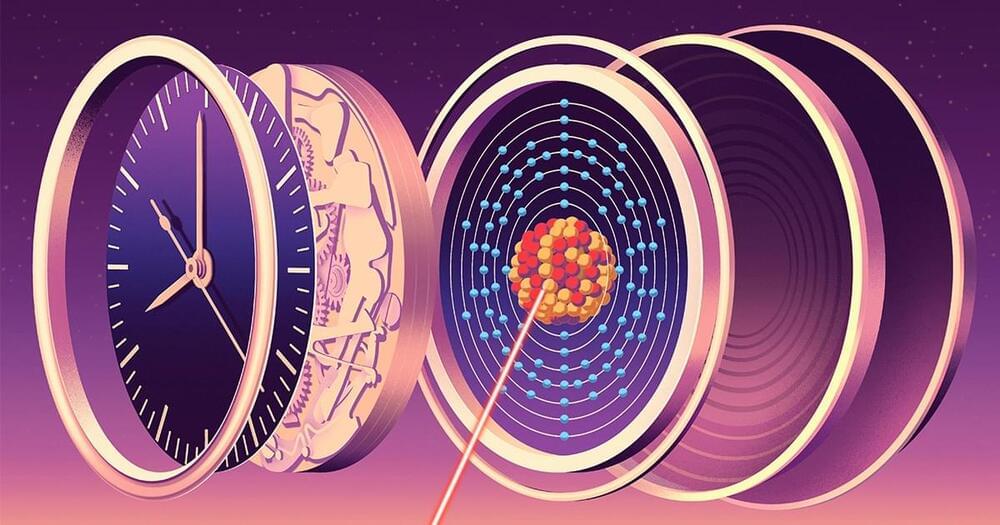

By creating indents on the reflective surfaces (shown on the left in an exaggerated form; the reflective surfaceis facing upwards), the researchers were able to imprint a structure ontothe photon condensate (right). (Image: IAP, Universität Bonn)

As an undergraduate he was drawn to theory, but he quickly switched to experiment.

“Theory was good, but I was driven to experimental particle physics because even if I write a theory, someone has to test it anyway,” says Gandrakota, who is now a postdoc at the US Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. “I’d rather be the person who tests and finds stuff than the person who predicts it.”

But he never lost his soft spot for theoretical physics. Today, Gandrakota and his colleagues on the CMS experiment are developing a machine-learning tool that will allow theorists even more freedom and creativity.

Thousands of light particles can merge into a type of “super photon” under certain conditions. Researchers at the University of Bonn have now been able to use “tiny nano molds” to influence the design of this so-called Bose-Einstein condensate. This enables them to shape the speck of light into a simple lattice structure consisting of four points of light arranged in quadratic form.