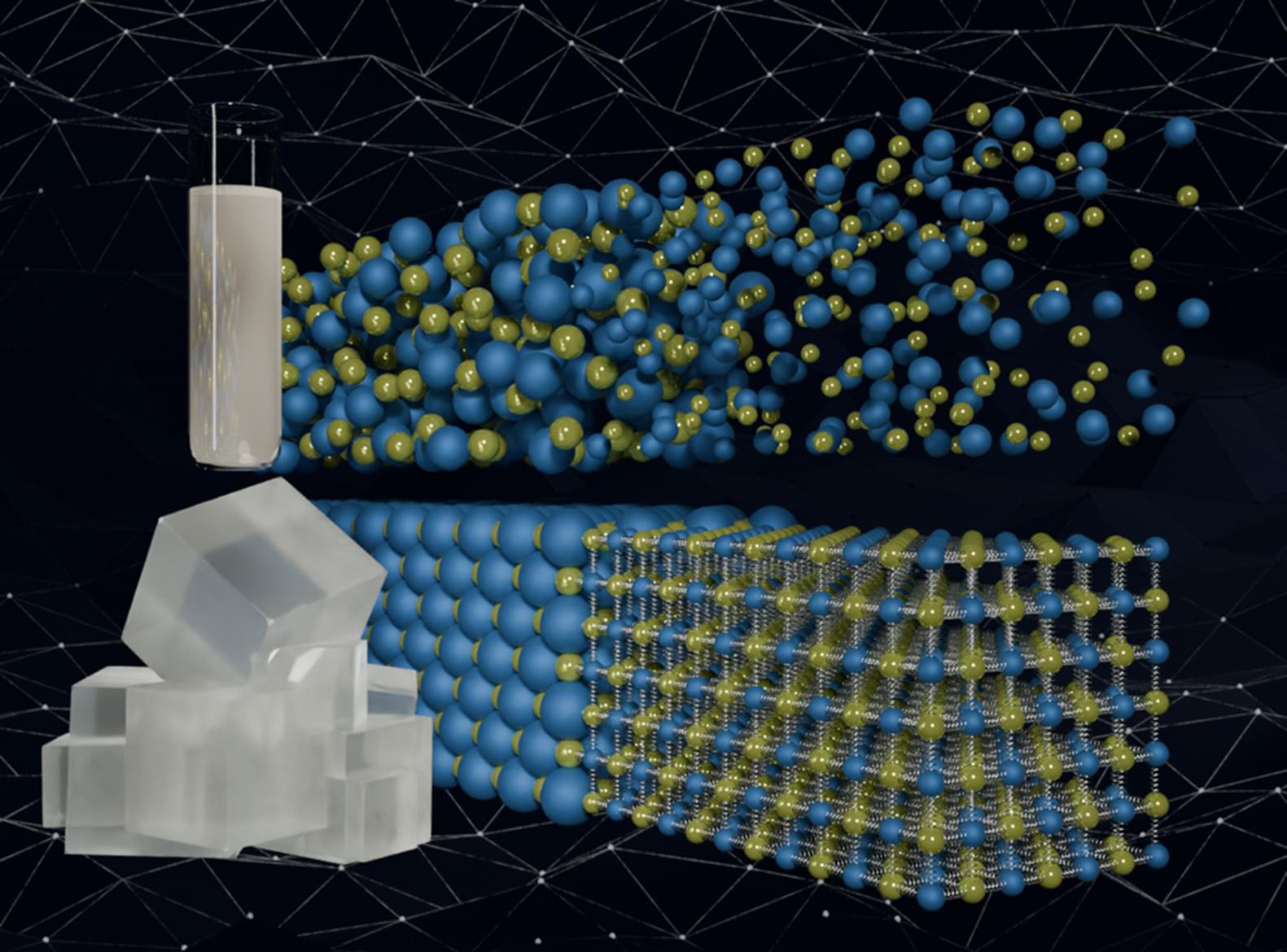

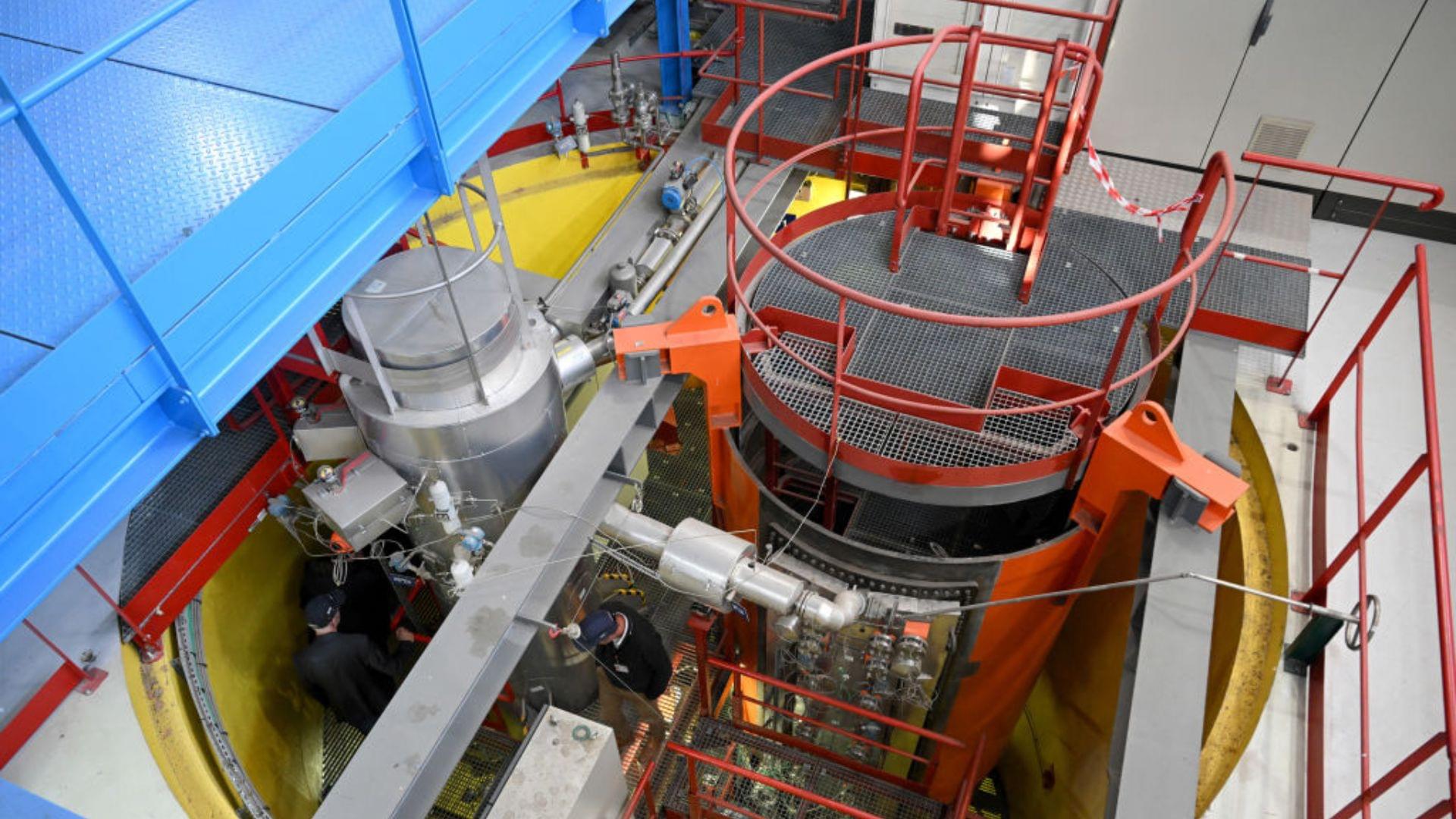

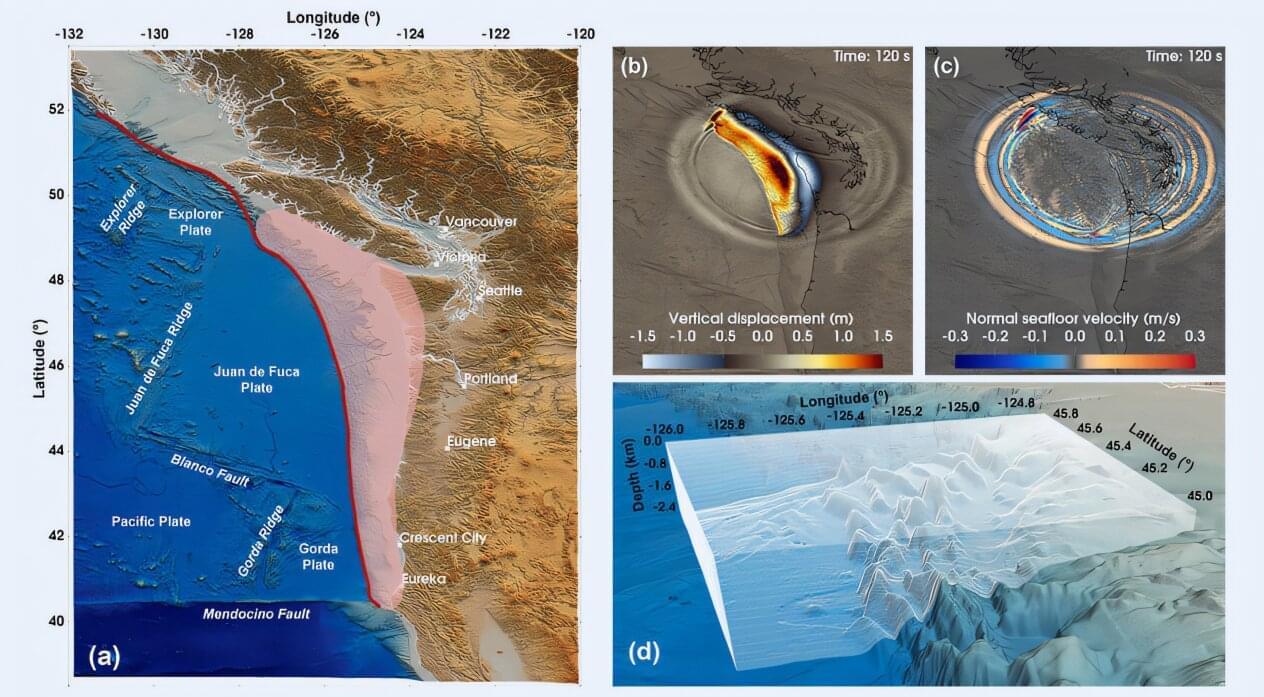

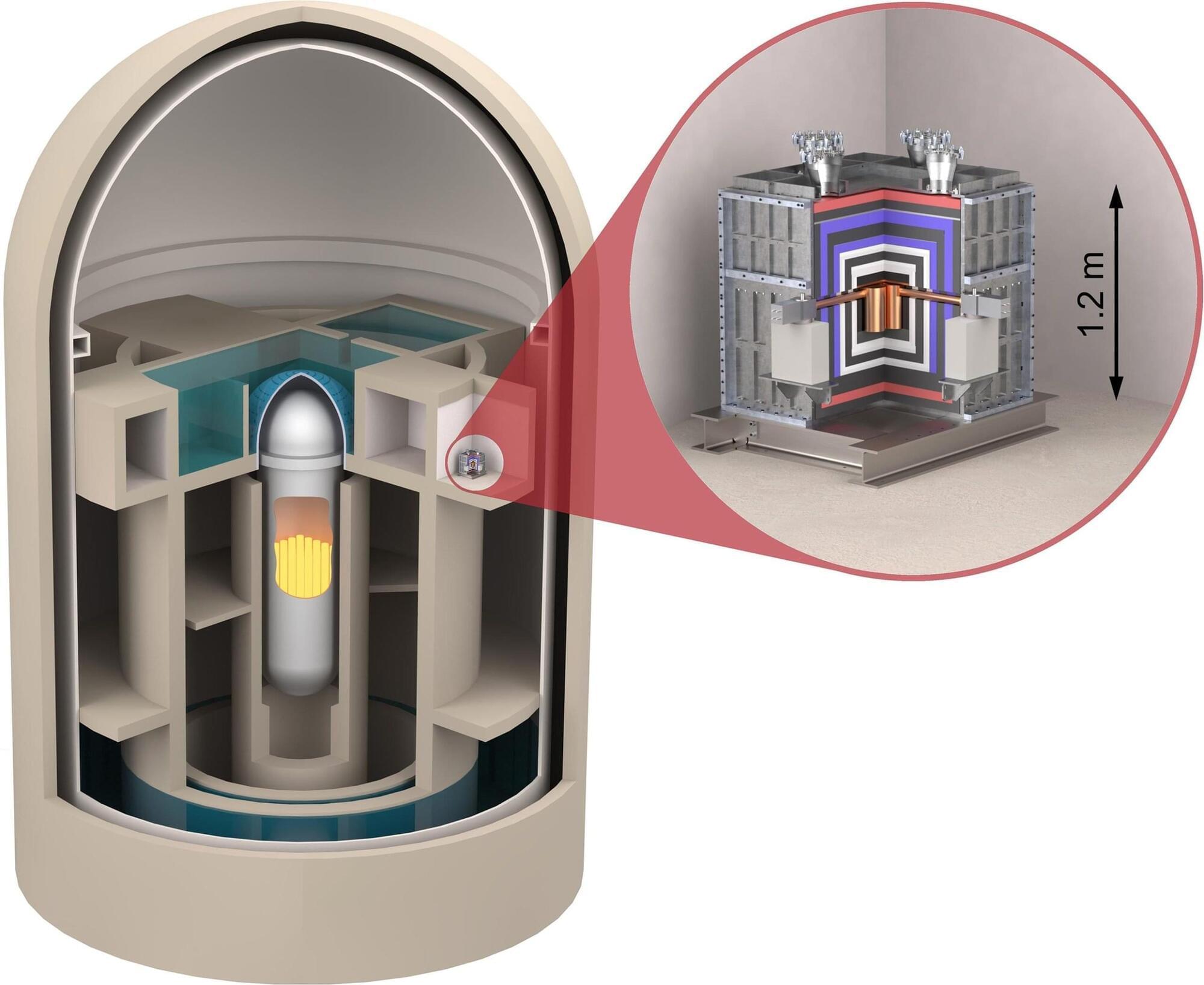

IN A NUTSHELL ⚡ China’s CFR-1000 reactor could supply electricity to one million homes, highlighting a major step in nuclear technology. 🔬 Utilizing fast neutrons, the reactor enhances fuel efficiency and supports sustainable energy solutions. 🌊 Innovative use of liquid sodium coolant allows for higher operational temperatures and improved efficiency. 🌍 Global implications arise as