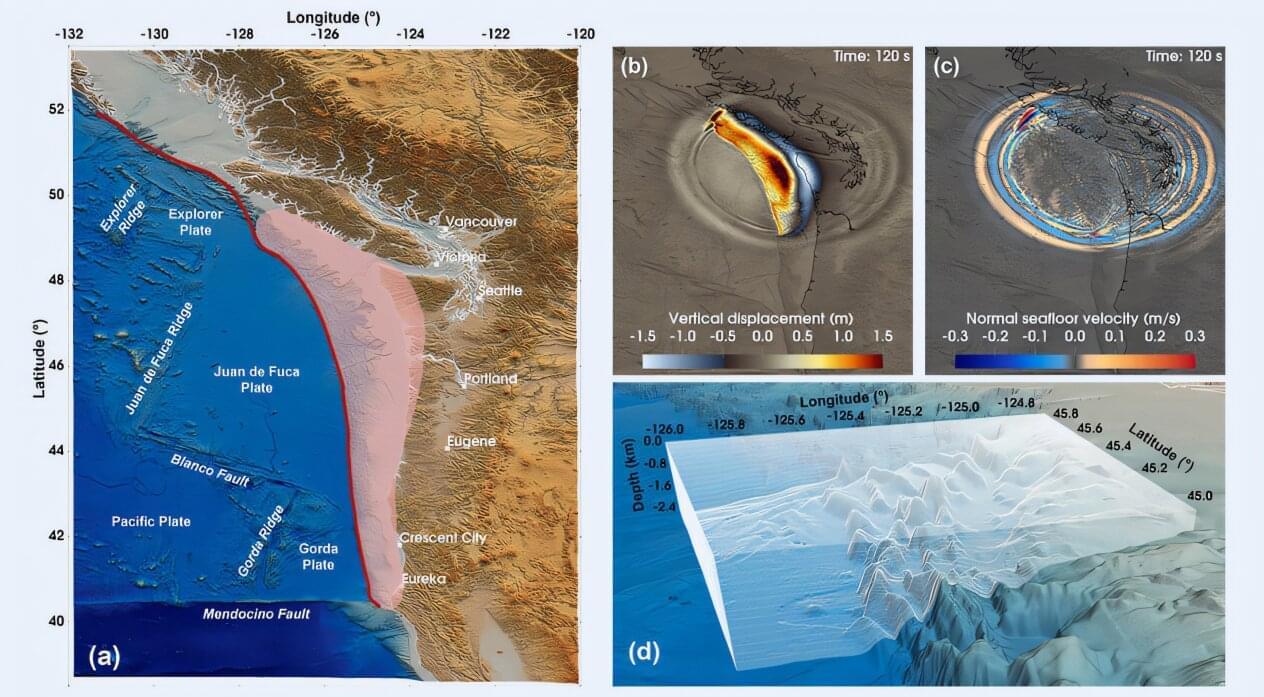

Scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) have helped develop an advanced, real-time tsunami forecasting system—powered by El Capitan, the world’s fastest supercomputer—that could dramatically improve early warning capabilities for coastal communities near earthquake zones.

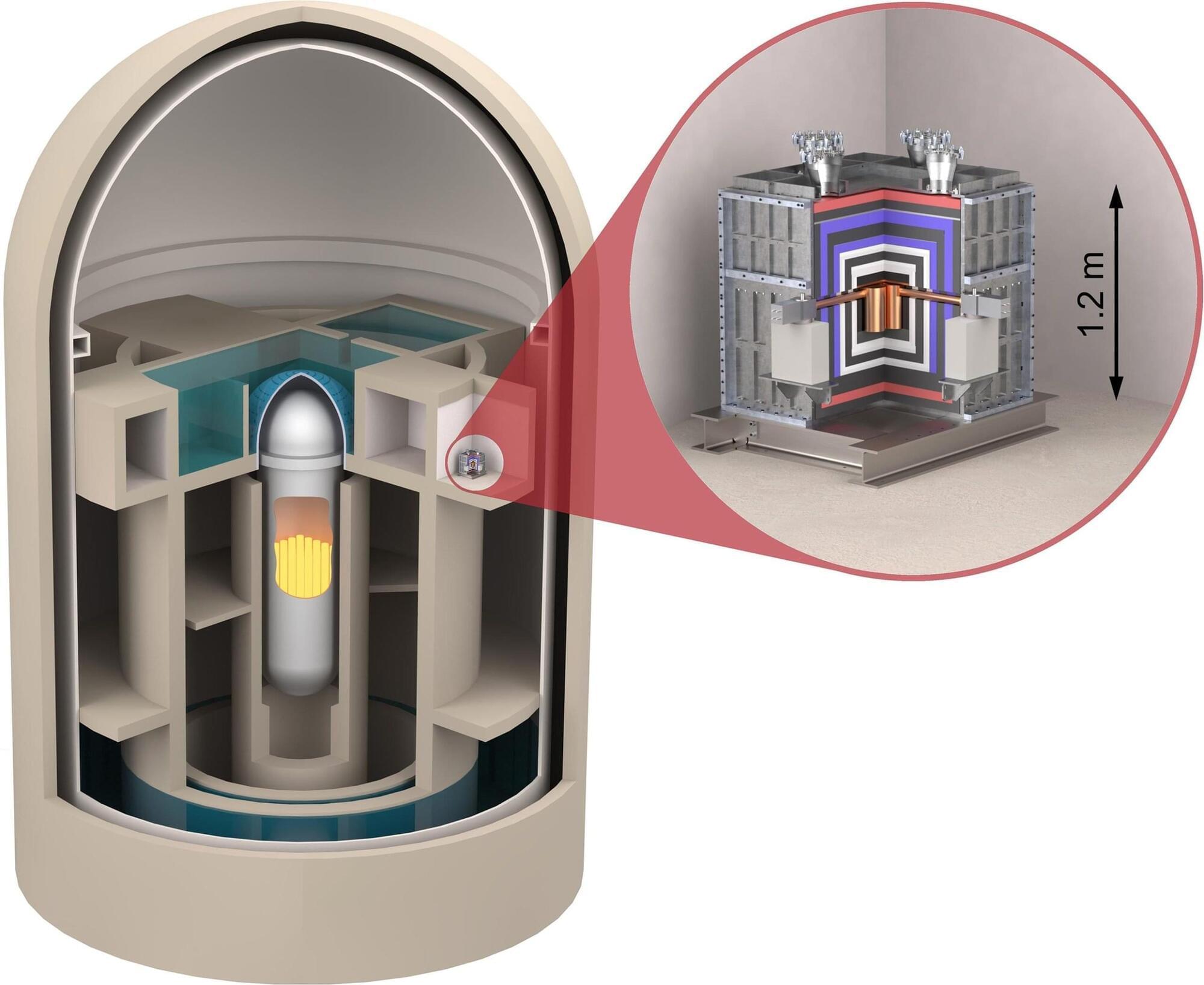

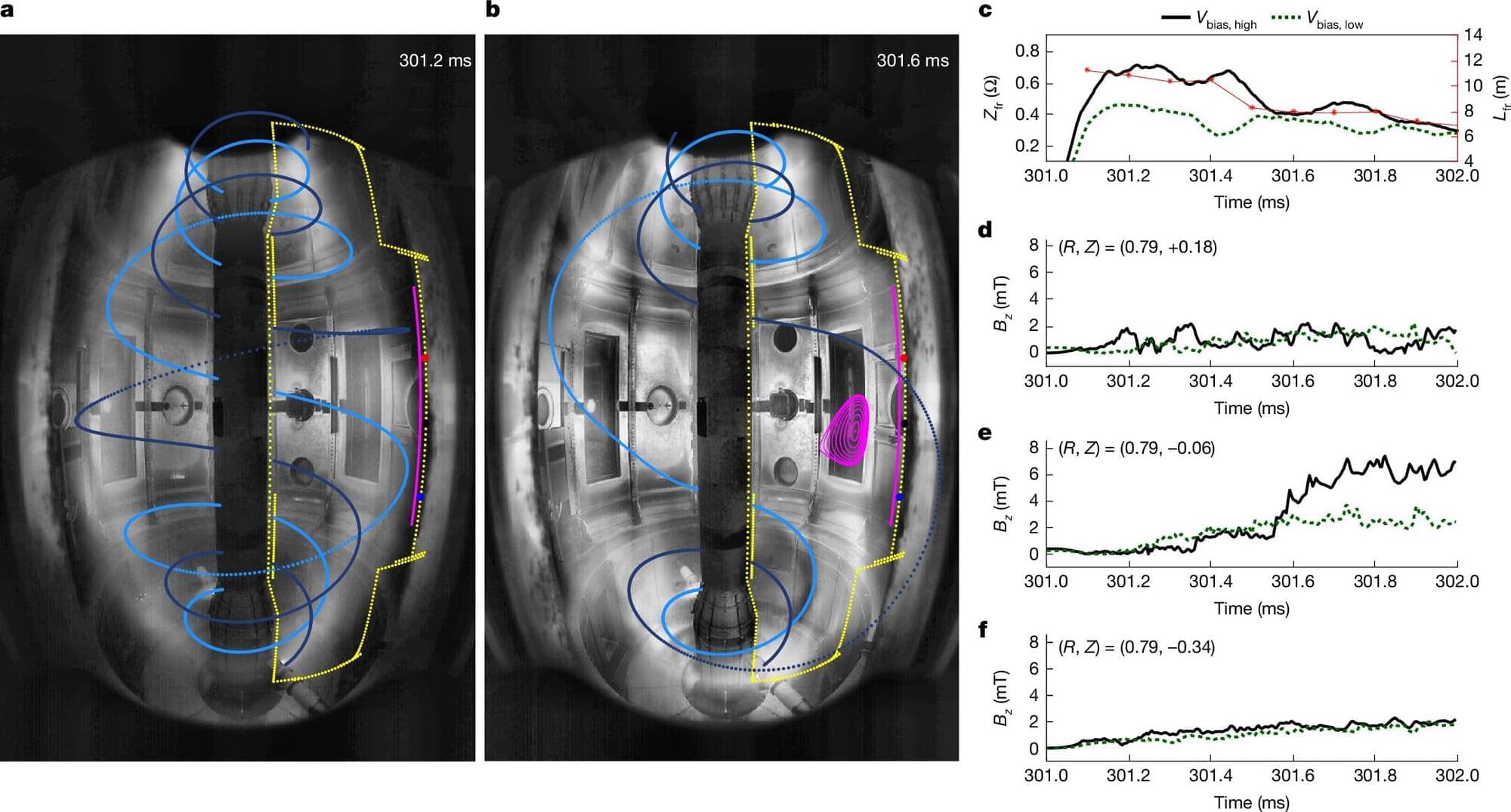

The exascale El Capitan, which has a theoretical peak performance of 2.79 quintillion calculations per second, was developed at the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA). As described in a preprint paper selected as a finalist for the 2025 ACM Gordon Bell Prize, researchers at LLNL harnessed the machine’s full computing power in a one-time, offline precomputation step, prior to the system’s transition to classified national-security work. The goal: to generate an immense library of physics-based simulations, linking earthquake-induced seafloor motion to resulting tsunami waves.

The paper is published on the arXiv preprint server.